Robert Mugge, the acclaimed music documentarian responsible for films such as Deep Blues, Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise, and Hellhounds on My Trail: The Afterlife of Robert Johnson, is visiting his mother at a retirement community in Silver Spring, Maryland, after editing his latest film, New Orleans Music in Exile, a feature-length documentary about the post-Katrina diaspora of Crescent City musicians.

“I’m overworked,” Mugge moans. “I’m completely brain-dead.” Although he was living in Jackson, Mississippi, when hurricane Katrina made landfall on August 29th, Mugge’s life was interrupted by the storm. This visit to see his mother is about the closest he’s come to R&R in the past seven months. His job as filmmaker-in-residence for Mississippi Public Television didn’t work out as planned, and Mugge was planning a move to Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, where he’d been tapped by Muscle Shoals producer and former Elvis sideman Norbert Putnam to create the school’s first department of music film production.

“Everything was supposed to be confirmed on September 1st,” Mugge says. “Then Katrina hit and flattened several of the casinos that pump money into the state’s education system.” Under the circumstances, Delta State was reluctant to commit to creating any new positions, and Mugge found himself adrift.

“That’s when I started looking for a silver lining,” Mugge says. “If you can call it that.” He went to Starz Entertainment group, which had funded previous projects, and pitched his plan to make a documentary about how New Orleans musicians were responding to the tragedy in the Gulf. Starz was interested, but Mugge would have to wait for funding.

“I kept pushing the idea of doing the film right away,” he says, “because at the time nobody really knew how long the musicians would be gone. It could have been a week, a month, or a year. I wanted to capture the shock. I wanted to show the desolation.”

Following a two-day shoot at the Voodoo Music Festival in Memphis, the funding came through to shoot in Lafayette, Austin, Houston, and New Orleans. The final film features concert footage and interviews with Dr. John, Irma Thomas, Eddie Bo, Beaten Path, Cyril Neville, the Iguanas, the Rebirth Jazz Band, Jon Cleary, Theresa Anderson, Cowboy Mouth, and others.

“I remember being up in the helicopter,” Mugge says of filming in New Orleans. “I told my cameraman that even though we’re up here with this camera, nobody will ever see what we’re seeing. You have to be able to see the horizon, all the blue [tarp-covered] roofs. And I became aware of all of these bare areas where houses used to be.”

Mugge was with revered junker-style pianist Eddie Bo when he went back into his ruined club for the first time. He was with Irma Thomas when she finally went back into her club. Both artists handled the shock with amazing calm as they pored through the rubble of their ruined lives.

“I’m glad I focused just on music and the musicians,” Mugge says. “But you could have turned the camera in any direction and there would be something worth shooting. You could go up to anybody and they would have a story to tell.”

Mugge also tracked the Iguanas — a roots-rock band that mixes American R&B with various styles of Latin music — to Austin, Texas. The band still seemed shell-shocked as they showed the filmmaker images of wrecked homes and ruined instruments on their computers. Cyril Neville of the Neville Brothers, who was also in Austin, spoke for the African-American community, saying that the 7th, 8th, and 9th wards must be rebuilt and the culture preserved. Certainly they were impoverished areas, but without them there would be no Mardi Gras Indians, and so much of the culture that defines Bourbon Street would just vanish. As Neville says, “That’s the roux in the gumbo.”

“There’s this place where Jan Ramsey [of New Orleans’ Off Beat magazine) points to a telephone pole and starts talking about how it’s a famous telephone pole because everybody used to hang flyers from their clubs on it,” Mugge says, relating one memorable scene from his film. “The flyers could get inches thick before someone took them down. After months of nothing, Jan says that posters are starting to show up again. It’s a wonderful symbol of the nature of this community — like a sprout coming up from dirt. Since it’s impossible to capture the magnitude of the disaster as a filmmaker, you have to look for these small, resonant images that suggest the larger situation.”

Mugge, who likens New Orleans to a dead body immediately after the spirit has departed, is hopeful that the cradle of American music will return to its former glory, but he’s also doubtful.

“I have all the same questions that the artists I’ve interviewed have,” he says.

Foreign Affairs

American distribution of the best international cinema has become increasingly spotty. Sure, the DVD explosion makes these movies more available than ever, but they’re meant to be seen in a theater, not on your television. Which makes the Memphis International Film Festival’s International Masters Series a public service worth looking forward to each year.

This year’s edition covers all the bases, culling celebrated cinema from Europe to Asia, Africa to North America. Here’s a quick guide to the year’s screenings:

Claire Dolan (9:30 p.m. Friday, March 24th): American indie filmmaker Lodge Kerrigan hasn’t been able to break through to any kind of national success despite stellar reviews for all three of his features: Clean, Shaven, a disturbing 1994 film about a schizophrenic; Keane, a 2004 film about a young man who loses his daughter in a bus terminal; and this 1998 feature, where the late Katrin Cartlidge plays a high-priced call girl determined to leave the business and have a baby.

La Promesse (2:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25th): Belgian filmmaking brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne won the big prize at Cannes last year for their latest film, L’Enfant. But while waiting to see if L’Enfant ever makes it to Memphis, you can see the Dardennes’ breakthrough film, the one that put their neorealist style on the international map. This 1996 film follows the 15-year-old son of a slum landlord, who breaks from his father to help the wife and infant son of a deceased tenant.

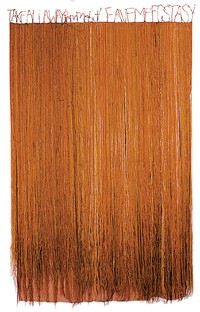

Moolaade (4:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25th): This 2004 film from Senegal’s octogenarian filmmaker and novelist Ousmane Sembene is the second film in a planned trilogy about African women, following the more comedic Faat Kiné, which previously screened at MIFF. Moolaade is set in an African village on a day where six adolescent girls are to be circumcised — a brutal and sometimes lethal practice.

Weekend (9:30 p.m. Saturday, March 25th): If you’re any kind of film buff and have never seen Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 farewell to narrative cinema on the big screen, then this is a must-see. Funny, provocative, and frustrating all at once, this apocalyptic flick about society collapsing under its consumerist preoccupations is utterly of its era and yet retains its power. A total classic with the best “car crash” scene in film history.

Quitting (2 p.m. Sunday, March 26th): Chinese director Zhang Yang’s funny, tender 1999 film Shower played Memphis, but we missed out on this 2001 follow-up — until now. The true story of a Chinese movie star (Jia Hongshen) battling drug addiction, with the actor playing himself.

Beau Travail (7:30 p.m. Sunday, March 26th): Dubbed a masterpiece by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum and named the best film of 2000 in a national critic’s poll, this reworking of the Herman Melville novella Billy Budd from French director Claire Denis concerns an ex-Foreign Legion officer who looks back on his life leading troops in Africa. — Chris Herrington

All screenings at Studio on the Square.