Jay Reatard Grows Up

Memphis’ garage-punk rising star on rowdy fans, obsessive collectors, prospecting record companies, and a career-changing embrace of melody.

By Andrew Earles

Since his 2007 appearance at Austin’s South By Southwest Music Festival, garage-punk savant Jay Reatard (real surname: Lindsey) has become the Memphis musician with the biggest national footprint in terms of press, hype, and relentless touring.

The first album he released under the Jay Reatard moniker, Blood Visions, came out in late 2006 on In the Red records. It was a slow grower, but, eventually, word spread. Lindsey assembled a back-up band with members of local scorchers the Boston Chinks, and live shows left audiences wanting more. The record itself showed maturity and a songwriting structure that blasted new life into the previously staid relationship between punk rock and pop.

Lindsey’s first band, the Reatards, which recorded on the then-new Goner Records label, was the hot garage-punk ticket in town during the late ’90s, when clubs were ruined and neck hairs raised by Lindsey’s undying passion, intensity, and indifference to safety. Then around 2000, he formed the Lost Sounds with then-girlfriend Alicja Trout, a prolific musician in her own right.

For most of the past eight years, Lindsey has juggled at least three bands, lended his recording/production hand to a steady stream of projects, and helped run Contaminated Records with Trout or Shattered Records with later girlfriend Alix Brown (formerly of Atlanta’s Lids). Ambitious almost to a fault, Lindsey has formed or played with the Bad Times (see sidebar), Angry Angles, Final Solutions, Nervous Patterns, Terrorvisions, the re-formed Reatards, and Destruction Unit.

Another prevailing element of Lindsey’s career is his proclivity for releasing limited-run vinyl singles across a wide landscape of small labels, thus nurturing a rabid collector’s market for his work.

At different points last year, Lindsey signed on with the burgeoning indie-culture empire Vice Management, weathered attention from both indie and major labels, and began a relationship with Matador Records that is now resulting in a series of six limited-edition, vinyl-only singles. (Matador will issue a CD/LP compilation of the singles later in the year.)

Several labels vied to release the studio-album follow-up to Blood Visions. When the Flyer spoke with Lindsey last week, he had just signed a Matador contract offer that had been on the table for months, one that has him releasing two proper albums for the label, with an option for a third.

On Thursday, May 1st, he plays what has become a rare local show at the Hi-Tone Café.

Flyer: When and why did you start performing as Jay Reatard and how did this band come together?

Jay “Reatard” Lindsey: I had recorded all of these songs that didn’t fit into the Lost Sounds’ style. When [Lost Sounds] broke up, I needed some sort of format for them. I was going to make up another fake band name, like I’ve done with a ton of different projects, but Larry [Hardy, owner of In the Red] said, “Why don’t you do it solo?”

At first I got a pick-up band with a guy who had played in the Reatards with me for years. I sent him the CD and told him to learn the songs and find a bass player. I didn’t even know that guy. Then I saw the Boston Chinks in town, and thought, Man, these guys have gotten so much better than they were a year ago.

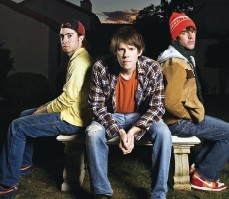

We’ve pretty much been touring for the past year. One guy quit, so we’re down to a three piece. Everything clicks now. I always thought that three people were all you need in a rock band. Three-piece bands just look better. You look up, and it’s symmetrical.

I remember Blood Visions being out for months before it got any attention. It was quiet for a while. How long?

It seems like anywhere from six months to a year. It seems like the past six months is when it’s really picked up.

Then you were the subject of a bidding war of sorts. What are some of the stories?

The first thing was, I got a MySpace message from this guy who was trying to be really inconspicuous about whom he worked for. He was asking a lot of questions, so finally I asked him to e-mail me, and his e-mail was a Universal Records address. I asked him if he was an A&R guy, and he said, “Yeah, when you get back to the states, I’d like to meet with you.” So, I met with them last July, around the time of the Pitchfork Festival.

Then Columbia Records gave me a call and said, “Rick Rubin is a big fan. He wants to meet you.” I happened to be in L.A., but things didn’t fit into his schedule, so I blew off Columbia. From there it was different indies. Vice was interested. Fat Possum, Matador.

It just came down to the slow process of trying to figure these people out and picking the best option. My gut feeling in the end was to go with Matador, the only ones keeping any of the promises they’d made along the way.

Did anyone want to re-release Blood Visions?

Fat Possum wanted to buy it from me, but it would have been an extension of me working with them, and I think that some of the major-label people down the line would have wanted to re-release it.

There was talk of cleaning it up a bit. “Can you remix it?” And I’m like, Wow, that’s funny. You really like this record. You want to put me on your label. But you want to change it? It’s like remixing the first Ramones record. It already sounds great, you know?

Whose idea was the singles series? You? Matador?

It was a mutual brainstorm. There were a lot of late-night conversations. I said, obviously, it’s going to take me a long time to figure out who I’m going to do my full-length record with, but there’s got to be a way for us to work together in the meantime.

The singles series became the best idea. It’s not too far-fetched from how I’d been working anyway. I’ve probably been putting out four or five singles a year for the past 10 years, so it seemed like a good idea to make it a cohesive project instead of a bunch of sporadic singles over a lot of small labels.

Have you run into a lot of people who are surprised by the format?

Yeah. I try to explain to people that it’s like an album to me but not as cohesive. There’s an aesthetic you stick to when creating [an album]. As a process, it can be grueling. It’s really fun as a songwriter to be able to go, Today, I feel like ripping off [’90s New Zealand-based enigma] Chris Knox; tomorrow I feel like ripping off the Adverts or whatever. Just jump around stylistically. I also wanted to do it as a process to help figure out what I want to do with my next album. The singles thing has given me a way to hear all of these different ideas that I have on record.

What is the run of each single?

The first single was 3,500 copies, and it sold out in a week. I was pretty impressed by that. I had no idea we’d move that many that fast. It goes in increments down from there. The second one comes out in a couple of weeks. That’s 2,700 copies. Then the next one is 1,300 on down to the last one being 400 copies.

Really? Why is it being staggered?

The idea was that the first single on Matador would be a lot of people’s introduction to what I’m doing. We wanted that one to be available. From there, I wanted to make collectable records. It’s kind of fun to watch this collector’s market that you create.

What’s the most ridiculous situation you’ve seen on eBay for one of your singles?

I did a tour single with this guy in Austria, who seemed to be an alright guy, and the agreement was that we’d do one pressing for a European tour and that I’d use the songs for something else later.

Unauthorized, he pressed it on a clear, six-inch square that plays from the inside out. He hooked his buddy up with a handful of copies and had this guy sell them on eBay, and they were consistently going for around $280 a piece. The guy was manufacturing records to go directly on eBay. He sent around nine copies to me. I gave them to people who I knew wouldn’t sell them. I lost my copy in a move. But I told the guy: Since you gave me nine copies, I’ll sell them on eBay and have enough money for a ticket to Austria to kick your ass. He chilled out after that.

In the past two years, it’s apparent that certain types of pop have had a big influence on you. What’s really blown you away?

At some point, I opened my mind to melody. As I get older, I listen to music that’s not as aggressive. I discovered this vast Flying Nun catalog that I’d never even heard of. There’s so many killer songs and so many great bands that came out of that, and it kind of changed the direction I’ve been going.

Also, I’d always hated U.K. punk rock. When I was playing in the Reatards, I thought domestic punk rock was so much better. I wrote off U.K. punk as really cartoonish. I’d never heard the Adverts until two years ago. What an amazing record [referring to the band’s 1978 debut, Crossing the Red Sea with the Adverts].

Are you going to keep Memphis as a home base?

I plan on being here for a while. People keep asking me, “Why would you stay in Memphis after all of this touring you’re doing?” Tell me one band that came from a small music scene, moved to L.A., and made their best record. I don’t think that too many people do things like that. If you take away the environment that’s inspired you, what are you left with?

More than the music of Memphis, the city itself has inspired me. I’ve always felt like Memphis has this weird, ominous cloud hanging over it. To me, that’s inspiring. I’m never bored. I always feel like I’m in danger. But to me, that’s exciting. I can’t imagine moving to another city. It would change the mood of everything.

Even though it’s really cheap to live here, there always seem to be things working against your survival.

Totally. To me, that’s a challenge. Unfortunately, that causes a lot of people to not be ambitious. Memphis artists are, historically, not the most ambitious people. They make great music but have no idea what to do with it. From the get-go, I tried to figure out how to get my music outside of the city.

For me, a lot of [the music] I like from Memphis are things that got close to breaking out, but something happened. It’s like a curse or something. I definitely love my city, I love playing here, but I’ve watched so many people expend so much energy trying to concentrate on getting a local draw and getting local press.

Can we talk about what happened last week in Toronto? [Lindsey punched an audience member at a Toronto club called the Silver Dollar after the man came on stage. The incident has been widely viewed after video of the altercation was posted on YouTube.]

Absolutely. That was the culmination of a year of people misunderstanding what I’m trying to do now. A lot of people read press and get this idea that the show is supposed to be this cathartic fuck-everything-up experience. Sometimes when I play a show, I just want to play my songs. There’s still a lot of energy. There’s just not this level of impending violence hanging over everything.

Some people decide that if I’m not freaking out enough, they’re going to try to inject something into the show that makes it this negative, violent experience. I’m fed up with it. It took me forever to save up enough money during my career to get to the point where I could afford things like a nice guitar and to have some guy pay $10 and think that entitles him to throw a beer pitcher at my guitar? I’m done.

People keep saying that they’ve seen the video on YouTube, and it doesn’t look like he did anything. When you have 350 people scaring the shit out of you, it’s like staring down the barrel of a gun. You’re a target up there. Sometimes I’m scared of the audience. I shouldn’t be. Obviously, you’re playing music to connect to your audience, but they are disconnecting by throwing things at you. I’m not going to stand up there and humor them. That’s not art or music at that point.

The kid who I punched had climbed on stage multiple times, and the last time he ran across all of my effects pedals and broke the cables. I think I was completely justified. Immediately after the show, I talked to the kid and told him that he was basically a martyr in the situation, that a lot of people were causing problems and making it impossible for us to perform, and that he just happened to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

You played three songs and had to pack up, right?

Yeah, it’s really frustrating. It’s exciting as hell to play Toronto seven or eight times and get to the point where you are selling out a show.

One of the YouTube videos, the one viewed the most, has the punch looped several times.

I kind of have the inkling that the YouTube video is an inside job. I have a feeling that it might be someone associated with one of the companies that I work with. I can’t prove it, but I’m almost positive.

A publicity stunt?

I’m not sure. I hope not. Unfortunately, something like that generates a ton of press. There are hundreds of blogs that have reprinted my apology letter. The promoter was obviously trying to make an attempt to save his own ass. He kept calling me “Jay Refund” and that they were the “Alamo of clubs” and that Jay has us surrounded.

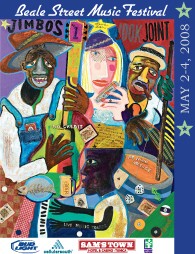

Sounds and Visions

Jay Reatard: a selected

discography.

By Andrew Earles

J. Allen

J. Allen

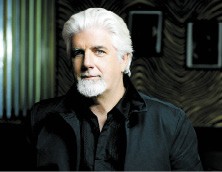

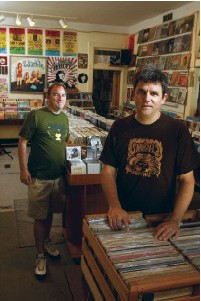

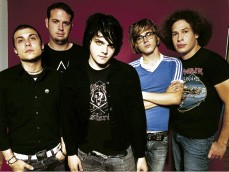

Jay ‘Reatard’ Lindsey (foreground) with Jeff Pope and Billy Hayes of the Boston Chinks

Grown Up, Fucked Up — The Reatards (Empty, 1999): The culmination of the first Reatards era, Grown Up, Fucked Up hints at Lindsey’s bottomless well of songwriting and is a suitable successor to the Memphis garage-punk throne vacated earlier in the decade by the Oblivians.

Bad Times — Bad Times (Goner/Therapeutic, 2001): An overlooked classic, this sonic brick-upside-the-head is an aggro-punk sucker punch from the garage-rock super group of Lindsey, Eric “Oblivian” Friedl, and “King” Louie Bankston. The cathartic, crap-fidelity steam hammer brings out the hate and will bum out those clamoring for Lindsey’s poppier side. But its power is to be appreciated.

Black-Wave — Lost Sounds (Empty, 2001): The Lost Sounds took a hard left from Lindsey’s previous garage-punk roots, steering their brutal post-punk with keyboards and electronics. The second in a four-album, five-year career, Black-Wave is the band’s biggest, best record.

Lost Sounds — Lost Sounds (In the Red, 2004): Probably because it was a little too poppy for diehards, the band’s final statement is the discography underdog and was not a critical or fan fave. The immensely enjoyable album deserves a close second look, as it occasionally represents a transitional phase in Lindsey’s songwriting, hinting at what was to come.

Blood Visions — Jay Reatard (In the Red, 2006): This wildly accomplished collection of searing pop gems will put understanding in the ears of newcomers. Blood Visions transcends the borders of garage, indie, and punk. Hooks and choruses explode from each song’s structural backbone. The shorter songs, most averaging a minute in length, are as fully realized as their longer cousins. Believe the hype.

“I Know a Place”/”Don’t Let Him Come Back” seven-inch — Jay Reatard (Goner, 2007): This is the perfect Jay Reatard single. The B-side cover of the Go-Betweens’ shambling pop heartbreaker is both telling and masterful.

“See Saw”/”Screaming Hand” seven-inch — Jay Reatard (Matador, 2008): For this release and the subsequent five singles in the series, most readers will benefit by waiting for the compilation CD/LP that will be released on Matador later this year. It’s no surprise that “Screaming Hand” is indebted to the Chris Knox vehicle, the Tall Dwarves. The garage-pop gold contrasts the poignant, lyrical statement about the tumultuous relationship between Lindsey and his father. — AE

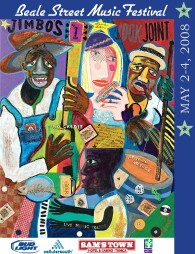

Paradise City

At 20, Shangri-La — the little record store on Madison Avenue — has lived a rich life.

By Chris Davis

In his novel Lost Horizon, James Hilton writes of an isolated Asian lamasery called Shangri-La, located high in the Himalayas, where the enlightened inhabitants are so filled with purpose, love, and inner peace that they have shrugged off death and become nearly immortal.

Shangri-La Records, the tiny music store on Madison Avenue in Midtown, across the street from the original Huey’s, can get a bit rowdy if the right band is playing in the parking lot. So no matter how serene Jared McStay, the store’s current owner, may seem as he sorts through new arrivals, his store can’t perfectly reflect the monastic calm ascribed to Hilton’s exotic utopia.

But the homey record shop, and its namesake indie label, celebrated 20 years in business earlier this year and has, over the years, known the touch of immortal hands like those of Charlie Feathers, the incomparable rockabilly pioneer who recorded classics such as “Tongue Tied Jill” and “One Hand Loose.” Feathers visited fans at Shangri-La shortly before he passed away in 1998.

Legendary Memphis garage rocker Sam the Sham, known for weirdo hits like “Wooly Bully” and “Lil’ Little Red Riding Hood,” has signed CDs on the porch. The savage Japanese rock-and-roll band Guitar Wolf once tore it up in the parking lot. Sub Pop recording artists the Grifters, who were, along with the Oblivians, one of the two most influential bands to roar out of Memphis in the 1990s, recorded much of their best material for the Shangri-La label. The store has since grown into a nexus for progressive musicians, preservationists, and historians alike, as well as an effective incubator for local musical talent.

For 20 years, Shangri-La has specialized in underground and edgy pop, Memphis music old and new, and vintage vinyl. It has become a true paradise for record collectors from around the world and a repository for useful, if sometimes esoteric, information, compiled for the benefit of adventurous tourists who want to immerse themselves in Memphis food, music, and culture. To that end, the record store has much in common with the fictional utopia for which it was named. And there’s something quieting, almost spiritual, about this place out of time where Memphis’ past and future collide.

One beautiful April day, McStay begins a familiar routine by sorting through a recently acquired stack of old soul and rockabilly singles, gleefully separating the good stuff from the junk. McStay, who was the principal songwriter and frontman for Shangri-La and Sugar Ditch recording artists the Simple Ones, says the current slow economy has actually had some positive impact on the store. For starters, the weak dollar has attracted bargain-hunting European tourists.

“When the Europeans ask for a discount, I tell them they got it when they got off the plane,” he jokes.

And as tragic as it may sound, whenever times get tight, record-store owners see an uptick of collectors who, for whatever reason, need quick cash and are looking to unload a lifelong collection.

A few feet away from McStay, Sherman Willmott, Shangri-La’s founder and the immodest personality behind the immodestly named Ultimate Memphis Rock and Roll Tour, prepares to hold forth on another, even older Memphis record store.

“I can’t believe nobody has torn down the Pop Tunes on Poplar,” he says, happily astonished, considering how everything else in the area has been modernized in recent years. “It’s been there for 60 years,” he continues. “It’s got to be one of the oldest record stores in the country.”

Willmott, who turned the store’s keys over to McStay five years ago to pursue his tour business and to expand Shangri-La Projects, recounts Pop Tunes’ pivotal role in the creation and evolution of the Hi Records label, which recorded Al Green’s most famous material. He worries that the historic location isn’t long for the world.

“When it finally is torn down, that’ll be a big chunk of my tour just gone,” he complains, bemoaning the fact that it’s a big Elvis stop too since the King shopped for records at Pop Tunes and his last job as an anonymous civilian was at Crown Electric, originally located just across the street from Pop Tunes.

“Hey, look at this,” McStay says, interrupting Willmott’s sermon by holding up a 45 rpm single with a cherry-red label. “It’s a Charlie Feathers on the Holiday Inn label,” he says.

“That’s pretty good,” Willmott responds, acknowledging that while he’s seen his share of Feathers singles and Holiday Inn singles, he’s never seen a Charlie Feathers on Holiday Inn before. It’s a perfect Shangri-La moment.

“One funny thing about the record store,” Willmott says, standing amid neatly organized crates of vintage vinyl, his arms spread out like an evangelical minister calling souls to Christ. “When it started, vinyl was virtually dead. The market (chain stores mainly) was rushing to rid itself of vinyl and vinyl bins, and the CD-reissue/box-set craze was just beginning. Now, almost 20 years later, most of the chain stores are gone. Wal-Mart, Target, and iTunes, as well as electronics dispensers like Best Buy, are the big sellers for Top 40. And many of the independent stores are throwing in the towel or reducing their total number of stores. Shangri-La Records has outlived most of the industry. And that’s pretty impressive for a store that began at the end of the vinyl era. And look at Goner Records in Cooper-Young. It’s going strong too, so Memphis is lucky to have not just one but two great record stores that are thriving.”

How Rhodes College’s big mistake led to Shangri-La’s conversion

Willmott, a graduate of Memphis University School, never intended to open a record store. In fact, the music business was the furthest thing from Willmott’s mind when he finished his undergraduate degree at Williams College and moved back to his hometown. His plan was something much weirder. In 1988, before there was a Hi-Tone Café or a Young Avenue Deli or any of the things easily associated with Memphis’ Midtown-centric rock-and-roll scene, Willmott opened a New Age-friendly relaxation center, offering massages as well as an opportunity to float in the kind of sensory-deprivation tanks featured in Ken Russell’s hallucinatory 1980 film Altered States. The business also offered a curious treatment called a brain tune-up, which Memphis musician Tav Falco once described as getting “psychodelicized.”

In a 1998 interview with The Memphis Flyer, 611 band member Brian Collins recalled putting on the special tune-up glasses. “You closed your eyes … and it was like when you’re riding in a car with the sun going down through some trees, the way the light plays on your eyelids,” he said. “You start to hallucinate.”

Willmott, who considers the center’s entire first year to have been a big waste of time and money, has pointed to the proliferation of day spas and described his relaxation center as being ahead of its time. Still, after 18 months in the relaxation business, Willmott realized that he wasn’t going to make his fortune from brain tune-ups or sensory-deprivation tanks.

Fortunately for Willmott (though virtually nobody else), in 1990 Rhodes College’s excellent community radio station, WLYX 89.3, was shut down by President James Daughdrill along with the whole of the college’s media department as part of what some have called a liberal purge. The one fortunate byproduct of the station being closed was the glut of used records that suddenly hit Memphis. Willmott, who once hosted a popular show on WLYX, acquired many of them. Shangri-La’s original inventory was culled from WLYX’s vast, diverse music library. Soon, Willmott had converted his shop into a full-time record store.

611 & The Grifters

In the late 1980s, a ramshackle house at 611 Patterson was occupied by a bunch of University of Memphis art students who liked nothing more than to smoke pot, take acid, and jam until the neighbors called the cops. The house became a fertile breeding ground for a group of musicians who would go on to be members of such memorable groups as the Simple Ones, Professor Elixir’s Southern Troubadours, the Idiot Patrol, and the Joint Chiefs. And it was the hangout of choice for members of K-9 Arts and the Grifters, as well as various folkies and assorted groupies.

Sculptor and installation artist Libby Pace was producing a lot of rock-and-roll shows at the time, and, on her recommendation, Willmott decided to record and release three songs by the Patterson house’s spacy house band, 611. It turned out to be a disaster since the band, which included future folkies Brian Collins and Michael Graber, as well as Two Way Radio drummer Joey Pegram, broke up immediately after playing their record-release party. Still, the artifact is a deliciously silly collection of stumbling songs about magic mushrooms, complicated relationships, and a Saturday-morning kids show from the ’70s called Land of the Lost.

“I don’t care how good a record is,” Willmott says. “I can’t sell it if the band’s not out there playing it.”

At the end of a long evening in 1992, a somewhat inebriated guy zigzagged through the thick blue fog of cigarette smoke and the thicker crowd of actors and artists who gather at the P&H Café on Madison Avenue every Thursday night. He was on his way to a dimly lit booth where the Grifters guitar player and co-vocalist Scott Taylor sat flicking a cigarette lighter, chugging a Zima, and chatting quietly with friends.

“I just got your CD today,” the fan blurted out, betraying, perhaps, a little too much excitement. “It’s really good,” he said, holding up a freshly opened copy of So Happy Together, the Grifters’ first LP.

“That’s it,” Taylor acknowledged sarcastically, rolling the one visible eye peeping out from a dark shock of unkempt hair that obscured half of the underwhelmed rocker’s chiseled face.

“Where’d ya buy it?” he asked pointedly, like a man with a big chip on his shoulder.

“Shangri-La,” the fan answered, surprised by both the question and the furious snarl that accompanied it. “Is there somewhere else you can buy it?”

“That’s good,” Taylor said somewhat approvingly. “Maybe Sherman can make a little money at least.” He then dismissed his speechless visitor with an icy, monocular glare.

Taylor is famously gregarious and his uncharacteristically terse behavior resulted from a frustrating record deal he, singer/songwriter Dave Shouse, inventive bassist/songwriter Tripp Lamkins, and powerhouse drummer Stan Gallimore made with Chicago’s Sonic Noise label. All of the Grifters were a little raw at the edges and ready to turn to Willmott, a friend, longtime advocate, and occasional business associate. He’d produced the band’s first release — under the moniker A Band Called Bud — a split flexi-disc distributed in the very first edition of Kreature Comforts, a ‘zine-style traveler’s guide to Memphis. His new Shangri-La label had also just put out a pair of astonishing Grifters singles: “Soda Pop”/”She Blows Blasts of Static” and “Corolla Hoist”/”Thumbnail Sketch.” Next came a couple of underground-classic LPs: 1993’s One Sock Missing and 1994’s Crappin’ You Negative.

The Grifters’ relationship with Shangri-La lasted until the group finally signed with Sub Pop in 1996. During that time, the band toured relentlessly and were widely considered one of the pillars of an indie-rock movement that included more enduring artists like Guided by Voices and Pavement.

“The Grifters are still our best-selling band,” Willmott says. According to McStay, he’s regularly asked by out-of-town customers who don’t know how to use the Internet when the next Grifters record is coming out.

Who You Calling

Preservationist?

“I was working on making the Wilroy Sanders CD and the documentary video The Last Living Blues Man when I started working for Stax,” Willmott says of the period beginning at the end of the 1990s and continuing into the first part of the new century. Shangri-La Projects was turning its attention to rootsier artists like the Fieldstones’ guitarist Sanders, a master of the minimal barroom shuffle and an alleged author of the blues standard “Crosscut Saw.”

“While I’ve done a bit of preservation stuff lately, everything I have done salutes the past but also includes the present and future,” Willmott insists, afraid of being pigeonholed as some “just looking at the past” kind of guy.

“Even the History of Garage Rock CD series brought things up to current times,” he says, referring to Shangri-La’s popular survey of garage rock in Memphis from the 1960s through the 1990s.

“The [next] Memphis Pop Music Fest [I’m putting together] will be two days long instead of one,” he adds.

“The main thing I’m working on now is promoting the new Antenna Shoes Generous Gambler CD, with a worldwide distribution deal that allows for downloads in virtually every country and with every company possible,” Willmott says.

There was no Internet when the Grifters were making waves at Shangri-La.

“Now I’ve got the best distribution I’ve ever had,” Willmott brags contentedly.

From the store’s earliest days as a relaxation center, Willmott and Shangri-La Projects have published Kreature Comforts. Each issue has begun with a somber disclaimer reminding tourists that, “as with any area rich in history, it is easier to tell visitors to Memphis where things used to be.” “This is a guide to what’s left,” the opening passage concludes.

When Willmott talks about the longevity of Pop Tunes, it seems as though he has a hard time wrapping his head around the idea that something like Willie Mitchell’s recording studio or a historic record store might find some way to perpetuate itself without intervention.

“Record stores just don’t last for 60 years,” he says. But apparently they do last for 20, at least, and thrive in spite of all early predictions.

Where They At?

By Chris Davis

For 20 years, Shangri-La has been an incubator for Memphis talent. Several of the record store’s first-generation staff members, who worked at the store from 1988 to 1998, have gone on to make a big impact on the local music scene. Andria Lisle and Andrew Earles have become published music writers in a variety of local and national publications (including this one) while delving into the record business as label-owners (Lisle’s Sugar Ditch) or performers (Earles’ two-disc comedy set Just Farr a Laugh is coming out this spring). Bassist Scott Bomar went from laying down a groove in cult surf-rock band Impala to giving local soul legends a second life in the Bo-Keys and scoring movies for Hustle & Flow director Craig Brewer. Eric Friedl, a founding member of the Oblivians, transferred his record love from clerking at Shangri-La to opening his own store, Goner Records. — CD

In the Mix

By Chris Davis

In addition to the Grifters’ catalog and the other Shangri-La-released products mentioned in this story, here are a few other items worth seeking out:

Man With Gun Lives Here: This eponymous 12-song captures the thundering hardcore barrage and insane math-rock changes that made Man With Gun the crusty, dreadlocked progenitors of a theatrical DIY scene that included groups such as Cop Out, His Hero Is Gone, and the incredible Taintskins.

Wattle & Daub — Strapping Fieldhands: This CD is chock-full of brilliantly weird pop like Pavement used to make. Is there anything more romantic than comparing your lover’s eyes to oscilloscopes while begging her to love you in increments?

I’ve Lived a Rich Life — Jeffrey Evans: Though actually released by Symphony for the Record Industry, this talky, autobiographical album was recorded in the Shangri-La parking lot and features some nice pictures of the place. — CD

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

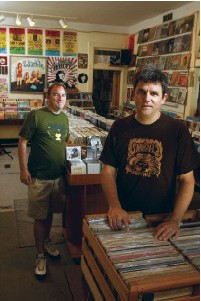

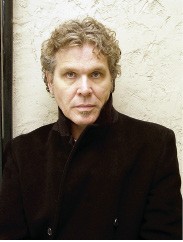

Sherman Willmott and Jared McStay

J. Allen

J. Allen

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Stefano Giovannini

Stefano Giovannini

Courtesy twovital.com

Courtesy twovital.com  David Moore

David Moore

Alice Stevens

Alice Stevens

C. Baldwin

C. Baldwin