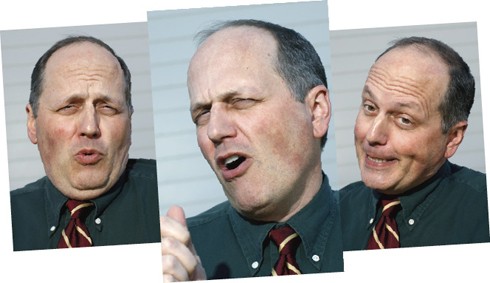

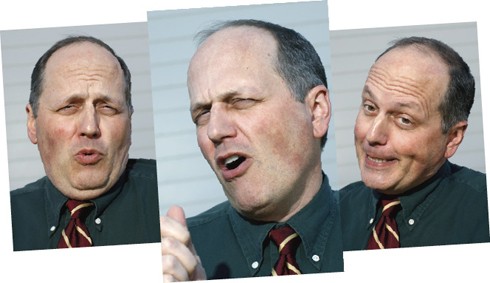

I was a smart aleck from early on,” Paul Shanklin says, reclining in a chair in the den of his expansive Cordova home. It is late Sunday night and indoors, but Shanklin is sporting one of the several baseball caps he habitually wears and which, like his ever-present grin, presumably serves to mask the ever-encroaching baldness which he jokes about openly, as if to say, Yeah, I’m sensitive about it, but I’m not sensitive about it.

When he goes on to say “I was the youngest child of five. I was a smart aleck who didn’t get killed in the process,” it is with that same having-it-both-ways ambivalence — a kind of equipoise, really — and it serves him well as a generally companionable sort whose function in life is to mock one whole section of the body politic, the political left, from the vantage point of the right.

Shanklin is one of the preeminent vocal impressionists around today, but rather than follow in the footsteps of such as David Frye, an all-purpose political satirist of the late 1960s, or Rich Little, whose voices covered the gamut of public personalities in the ’70s and ’80s, Shanklin has no interest in doing road tours, or being everybody’s darling on Letterman and Leno, or playing the Vegas stage to universal applause.

The 47-year-old part-time financial planner is a homebody who likes hanging out with his wife Angie and two sons and is content to earn a living — “good enough to let me live in Cordova” — by playing the fool on arch-conservative icon Rush Limbaugh’s hugely popular (or widely abhorred, depending on one’s politics) syndicated radio show, ragging the personalities of the left — both Clintons, Al Gore, John Edwards, Barack Obama, whomsoever — with what sound eerily like self-damning lyrics said or sung in their own voices.

“I try to imagine what they’re really thinking,” says Shanklin, whom I’ve known since the early ’90s, when, as the owner of a suburban ServiceMaster franchise, he first ventured onto the public airwaves on local radio stations like Oldies 98 and Kix 106, doing impressions of Bill Clinton, or Ross Perot, or whichever target du jour suited him.

That was at the behest of then Commercial Appeal editorial cartoonist Mike Ramirez, whom Shanklin admired both for his graphics and his politics, which hued as far to the right as his own. (Raised in the Church of Christ and schooled at Harding Academy, Memphis native Shanklin chose not to rebel against his background but against those politicians who had rejected the inherited conventions of American life.)

Shanklin called up Ramirez on a fan’s mission and was taken up by the cartoonist, who enjoyed the impressions he heard Shanklin do when the two played golf and became a missionary on his behalf. One day in 1993, at Ramirez’s urging, Shanklin made bold to contact the Limbaugh show and reached producer Johnny Donovan, who told Shanklin, “Okay, send a tape.”

Shanklin put one together, sent it, and heard nothing. So he sent another. Still nothing. He contacted Donovan several times and was finally told, “Yeah, we got it. Thanks. We’ll be in touch.” And then nothing all over again.

Finally, in desperation, Shanklin called up Donovan and said, in his best Bill Clinton voice, “John, this is Bill Clinton. I don’t know how it happened, but Rush and I are not as close as we used to be,” then proceeded to ask the producer to help straighten things out between the nation’s reigning Democrat and the radio host for whom Democrat-bashing was an end in itself.

There was a pause on the other end of the line. Then an obviously impressed Donovan said, “That was great. Who is this?” When Shanklin told him his name again, Donovan responded, “Can you send me a tape?”

Shanklin laughs long and delightedly when he gets to the punch line of this tale. It is, after all, a joke on himself that ended well. He has been a fixture on the Limbaugh show ever since.

His demeanor becomes more sober, even troubled, though, when he reflects on the most recent consequence of his celebrity — the controversy that has kicked up not once but twice over what he regarded as something of a throwaway lyric on the most recent of his self-produced CDs, one entitled We Hate the USA — the “we” being the likes of Hillary Clinton, Jesse Jackson, Al Gore, and, of course, the Democrats’ man of the hour, Barack Obama.

That problematic song is “Barack the Magic Negro,” sung to the tune of the old Peter, Paul and Mary offering, “Puff the Magic Dragon,” and featuring a Shanklin impression of the Rev. Al Sharpton. It is a multiply enveloped piece, a bit too complicated, Shanklin acknowledges now, for the satirical message of the song to fully register as he says he intended it to.

It depends on one being aware of an established archetype — that of the “magic Negro,” a black figure who turns up in various dramatic or literary texts as a deus ex machina figure who offers a white central figure a way out of his dilemma in such films as The Defiant Ones and The Legend of Bagger Vance.

The next envelope involves “Obama the ‘Magic Negro,'” a 2007 column by multi-racial writer David Ehrenstein in the Los Angeles Times. In that piece, Ehrenstein focused on the adulation even then being trained on an up-and-coming Obama by a liberal intelligentsia determined, as he put it, to “project all its fantasies of curative black benevolence on him.” Sharpton figured in the column, along with rap artist Snoop Dogg, in Ehrenstein’s snide reference to “sterling examples of ‘genuine’ blackness.”

Bingo! Shanklin, who thinks up most of the recorded riffs he supplies Limbaugh at the rate of two a week (the host occasionally suggests one, editor-like), saw a satirical opening and wrote and sang lyrics that, arguably, went after both Obama and Sharpton — each for a different kind of imposture.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Paul Shanklin

The frame of the song presents activist Sharpton as a self-serving opportunist who sees the spotlight moving off himself and jealously intones such lines as:

The media sure loves this guy,

A white interloper’s dream!

But, when you vote for president,

Watch out, and don’t be fooled!

Don’t vote the Magic Negro in …

Fair? Unfair? Who knows? It’s polemical commentary, after all, and when is that ever really Fair and Balanced? The problem was that, unlike the relatively sophisticated voices that Shanklin assumes for such African-America personages as Obama and Jackson, the one he used for Sharpton was, like the activist’s own, relatively coarse — that of a “street preacher” shouting through a megaphone, Shanklin notes.

And all it takes to generate a first-rate controversy is that such a voice, plainly being affected by a white man, be heard gabbling out an intro like “Barack the Magic Negro/Lives in D.C.” Shorn of the entire lyrics or of the several enveloped contexts of the parody, it could — and did — sound, as Shanklin concedes, “contemptuous and bigoted,” like a modern-day version of the infamous “coon shows” which once flourished in the post-Civil War segregated South.

Heard over and over on the Limbaugh show, the song generated an immediate negative reaction back in 2007 (as well as, face it, a delighted one in several suspect quarters). That controversy erupted all over again within the last month when Shanklin pal Chip Saltsman, an ex-Memphian who managed the 2008 presidential campaign of former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee (which Shanklin also worked in), sent the We Hate the USA CD as a Christmas gift to the members of the Republican National Committee.

Saltsman meant thereby to court the RNC members in his quest to become national Republican chairman — a post that will be awarded to one of several aspirants for the job later this month. Call that decision a misjudgment or call it a mischance — whatever it is, it has, by general consensus, doomed Saltsman’s hopes, drawing astonished denunciations not only from the left but from most of Saltsman’s opponents in the Republican chairmanship race and from mainstream GOP figures, ranging from former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich to Shelby County’s own John Ryder, a Tennessee national committeeman and a voter in the chairmanship sweepstakes.

It even drew the righteous wrath of Peter Yarrow of the Peter, Paul and Mary trio and the co-author of “Puff the Magic Dragon,” on which Shanklin’s parody is based and which has enjoyed a vogue as a children’s song that continues through today.

Writing for the online Huffington Post site, Yarrow condemned the parody and declared that “taking a children’s song and twisting it in such vulgar, mean-spirited way is a slur to our entire country and our common agreement to move beyond racism.”

Again maybe so, maybe no. But in evaluating this and other responses to the “Barack the Magic Negro” controversy, it helps to remember that Newsweek magazine and a slew of other commentators back in the day published exegeses of “Puff the Magic Dragon” that credibly impugned its lyrics as larded with coded drug references — “Little Jackie Paper” and “a land called Honah Lee” (Hanalei, the Hawaiian site of a notoriously potent strain of marijuana) being but two such.

Right. Judge not lest ye be judged. And, Shanklin’s no doubt honest protestations notwithstanding, it is equally possible for both casual and serious critics to make the case that emerging from his song’s several layers of meaning is a bona fide racial thrust. Words sometimes mean what they want to, whatever their author believes their intent to have been.

Again, consider the title We Hate the USA and Shanklin’s statement of method on how he approaches the subjects he parodies: “I just try to imagine what they’re really thinking.” Can he possibly imagine that the two Clintons and the president-elect, among others, actually “hate the USA”?

The question makes Shanklin pause. “Some of them do. Their actions do,” he says, without elaborating.

Whatever the case, Paul Shanklin definitely has his fan base. His several CDs, produced these days from a self-built studio in his house, are well and widely known. I found that out when I was in St. Paul, Minnesota, last summer to cover the Republican National Convention. I was waiting, along with Shanklin and a longish queue of other people in a fast-food line just off the main floor of the convention arena. On an impish impulse, I said, “Paul, why don’t you do ‘Barack the Magic Negro’ for these folks?” Instantly, several heads turned around, and murmurs went around, all on the theme of “That’s Paul Shanklin!” He ended up having to do an impromptu concert, answering requests that ran the range of his vocal panoply.

But even in non-Republican circles Shanklin has admirers. His next-door neighbors in Cordova, a black couple whose yard signs boosting Democratic candidates in last fall’s election conterpointed Shanklin’s own GOP-themed ones, made a point of coming to the door to express their support for him at the height of the most recent “Barack the Magic Negro” controversy.

And only last Friday, while he was resting up from a photo session that he’d found grueling, Shanklin answered a knock at his door to find an African-American woman bearing a piece of paper. Uh oh, he thought warily. What’s that, a complaint?

Instead, it was a request for the now notorious parodist’s autograph.

Paul Shanklin, after all, belongs to a long comedic tradition. He is a “fool” in several obvious senses of the word, including the Shakespearean. Never mind that at this stage of his career, he most closely resembles the boil-in-the-ass version in King Lear. More scourge than jester. He knows how to do what he does. And he is one fool who apparently will be suffered for some time to come — whether gladly or not.

pic courtesy of Angie and Paul Shanklin

pic courtesy of Angie and Paul Shanklin

On Halloween, Angie and Paul Shanklin play you know who in Cordova. (And if you DON’t know, it’s Palin and McCain, of course.)

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  pic courtesy of Angie and Paul Shanklin

pic courtesy of Angie and Paul Shanklin