A thirty-three-year-old son with massive debt, a felony conviction,

no job, no home, no spouse, two children, and accumulated assets that

fit into two cardboard boxes.”

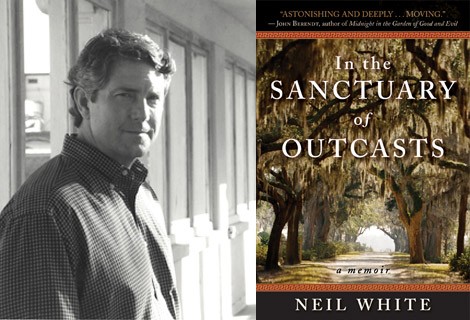

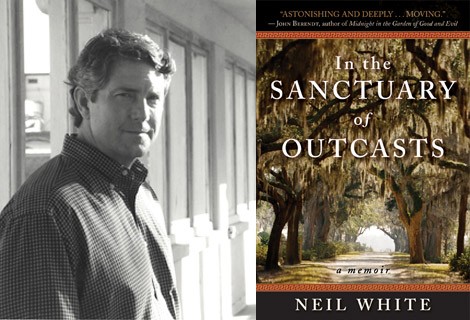

That’s how Neil W. White III describes himself at one point in his

memoir In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (Morrow) — a bad state

to be in, sure. But on April 25, 1994, White wasn’t sad so much as

relieved — relieved that his sentence of 18 months in federal

prison had been reduced to just under a year due to a decision by

prison authorities.

Those authorities had been conducting an experiment: housing

minimum-security inmates (petty criminals; white-collar criminals) at

the Federal Medical Center in Carville, Louisiana, outside Baton Rouge.

The medical center had space to spare, but it was also the last

leprosarium in the continental United States — “leprosarium,” as

in a hospital for those afflicted with leprosy (or Hansen’s disease),

which, to this day, has no cure.

What was Neil White doing there? Time — for bank fraud, for

“kiting” checks, and for “factoring” invoices to keep his cash

flowing.

He’d also cost bankers a million dollars. He’d lost the money his

investors trusted him with, including his own mother’s money and trust.

Still, in April 1994, White was a released man. He was also a different

man.

Different from the man, age 24 and straight out of Ole Miss, who

launched (and lost) an alternative newspaper in Oxford, Mississippi, in

the ’80s But he went on to publish city, regional, and business

magazines in Mississippi and Louisiana, including Coast

Magazine, Louisiana Life, and New Orleans

magazine.

Times then were good, and White was the husband of a lovely wife and

the father of two children. But finances remained shaky. And that’s

when the fed got wise to White’s “creative” banking practices. He was

exposed in the spring of 1992, and roughly a year later he entered

“Carville,” the site of a former sugar plantation and the setting for

White’s moving memoir.

It’s where White (and readers) meet a streetwise charmer named Link

and a master at medical fraud (and White’s cellmate), Victor “Doc”

Dombrowsky. It’s also where we meet Frank Ragano, Jimmy Hoffa’s lawyer,

and Dan Duchaine, a former bodybuilder who went on to outwit Oympic

authorities on the use and abuse of steroids.

And then there are those afflicted with Hansen’s disease. It’s a

population that the inmates at Carville socialize with, and it’s a

population that White, who’d always placed a premium on good

appearances, was initially horrified by.

It’s also a population that turned White around — around from

the notion that he was simply “undercover” at Carville, a reporter with

a job to do, and around to the notion that he was not only guilty, he

was ashamed, ashamed of what he’d done and ashamed of the high-priced

life he’d been leading.

As White told the Flyer, “I was surrounded by people who

could not hide their disfigurement, and all of a sudden I saw mine.”

All of a sudden, too, White was faced with the possible loss of his

children to divorce.

Good news, though: White has since remarried — to an Ole Miss

law professor. He lives in Oxford. He runs a publication company, but

the stakes are low-level, less risky. And he’s at peace with the work

he does — as a businessman, teacher, and active member of his

church and community.

More good news: White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts, which

he’s waited 15 years to write, is more than a memoir. It’s most

importantly a testament to the patients at Carville and the life

lessons they gave and White took.

Giving/taking: Proceeds from the sale of White’s book will go to

advocacy groups protecting the rights of people afflicted with Hansen’s

disease — a dread disease still. Readers will be, in the bargain,

taking an honest look at Neil W. White III, a freed man.

For the Flyer‘s Q&A with author Neil White, see

below.

Neil White signing and reading from In the Sanctuary of

Outcasts

Burke’s Book Store, Thursday, June 4th, 5:30 p.m.

Square Books, Oxford, Saturday,

June 6th, 5 p.m.

Flyer: How does it feel — In the Sanctuary of

Outcasts finally in stores, 15 years after your release from

prison?

Neil White: It’s been exciting, a little scary, and a long

time in the works. It’s been a healing but difficult birth.

I debated for years whether to write this book for my kids and

family or to publish it. I wavered.

The writing was therapeutic. But publishing the book was counter to

what I learned while I was in prison. You know: Don’t look for

applause. Do deeds quietly without concern for what people think. Keep

things simple. But I made the decision that it was important to tell

the story, to put myself at risk.

A story that’s not been widely reported.

Carville was unique — a convergence of cultures. And nobody

seemed to be paying attention to this experiment where leper patients

and federal convicts lived together.

It was prison and it was difficult, but it was an

amazingly rich time for me.

Do you wonder how you would have fared in a more dangerous

prison, one with tighter security? Would it have been as “amazingly

rich”?

I would have fared terribly. I wouldn’t have done well at all. The

black inmates at Carville made unmerciful fun of me for trying to be

polite: “Man, this is prison. What the hell are you doing?” Or,

“Man, you are lucky you are not in a real prison.”

There were no bars on the doors at Carville. We were free to move. I

didn’t have to worry much for my physical safety. I was able to focus

on what I needed to do. I could examine my own life.

People in places where the primary goal is survival don’t have that

luxury.

The scene in your book inside the chapel at Carville …

the one where you finally come to grips with your full guilt. Care to

expand on that?

I tried to leave that scene out, because it’s a cliché, but

everybody hits rock bottom at a different place, whatever the problem

may be. The “undercover” scenario I’d invented for myself was clearly a

defense. But more than that, I was denying that I deserved to be in

prison at all, that I had done anything that would merit

incarceration.

I argued to myself: What does this mean, to be convicted of bank

fraud? I was kiting checks, yes. But the false bank balances I created

… the banks were selling them to the fed to make interest overnight

on them. We were in business, in “bed” together. And some third-party

comes along and charges me with “rape”? What’s this about?

I was in total denial all the way around.

And this is where you get into the issue of “personality.” What kind

of person becomes a Bernard Madoff? A white-collar criminal?

I think it’s the person, like me, who is so able to convince

themselves of their worth, their entitlement, their right to cut

corners — that what they’re doing is so great, so important

— rules can be bent.

When I thought, inside Carville’s chapel, that I was going to lose

my kids, though, it occurred to me I’d ruined lives, betrayed

loyalties, had not asked for help.

I’d lost my mother’s money. I’d lost an investor’s money, to the

point where she lost her home. It was embarrassing that it took

me so long to get “there.”

In that chapel, among those with leprosy, I was surrounded by people

who could not hide their disfigurement, and all of a sudden I saw

mine.

This is not a religious book by any means, but all religions …

before you move on, you’ve got to admit what you’ve done wrong, whether

you call it penance or not. I had not done that.

I’ll need to be open to making amends for probably as long as I

live.

You don’t cover this in detail in the book, but what has life been

like since you were released from Carville in 1994?

Most of the people I reached out to have been very forgiving.

Oxford, Mississippi, has been very forgiving.

After leaving prison, I was confined in New Orleans to a halfway

house for six weeks. I had restitution to pay each month, child support

each month, insurance premiums, plus everyday expenses. I didn’t have a

choice but to go back into business for myself. But I couldn’t afford

failure.

Now I’m working out of the house. I never take money upfront. I

deliver more than promised. I try to keep it small. City and regional

magazines again? I can’t risk it. I’m strictly doing custom publishing,

for colleges, hospitals, banks, student magazines; pro bono work for

theater groups, writers’ groups, start-up film festivals, for people

who can’t afford an ad agency or a large publishing company.

It’s not exciting work. It doesn’t win awards. But it pays the

bills. And I feel good about what I’m putting out in the world.

Tell me about your path to publication.

I knew the material was there, but I needed time to figure out what

it all meant, why it was important. I didn’t want flowery language to

interfere. I wanted to keep the story accessible, let the story be

impactful, not the writing. So I waited.

Five years ago, I was in a workshop for creative nonfiction led by

Lee Gutkind, who was supportive. He shepherded me along. That’s when I

made the decision to write this story for publication. Others in the

workshop said to me, “You can’t not write this.”

Then I was at a creative-writing conference and an agent, Jeff

Klein, said, “I hear you have a story.” I told him yes, but I’m not

ready. Well, he hounded me every three months for two years.

When I finally told him I’m ready, I’ll have a manuscript for you in

about a year. Jeff said, “For God’s sake, don’t write it! You’ll just

have to rewrite it. Let’s get a book proposal and an editor who’ll help

you work through this.”

I was kind of shocked. I had an agent hounding me. We went

with publisher William Morrow.

But here was the quandary: I knew the one-line hook for the book:

that they put federal convicts in a leper colony. When you said it,

people started asking question. So I knew there’d be interest, but I

didn’t want to sensationalize it. When people say they can’t believe

I’ve waited 15 years to write this book, I say I couldn’t have done it

any other way.

Do you have another book in mind?

This one took so long and so much out of me, I don’t want to jump

into another book right now. But I have adapted In the Sanctuary of

Outcasts for the stage. I wrote it as a play in 1998 and called it

Lepers and Cons. I’ve workshopped it in Oxford.

And your parents: their reaction to the book?

My father: He loved it. My mother: She’s now a minister in Gulfport.

She’ll have a bank president sitting next to a homeless person, and

that’s the way it should be. She’s amazing. She loved the book. My

mother likes the spotlight regardless of the shade of light.

But I want to say my name is on this book. But it’s not my

book. So many shared their stories with me. It’s our book.