This week’s Flyer editorial offers some perspective on the long tenure of Mayor Herenton.

Month: July 2009

Ostrander Nominees

On Sunday, August 30 the Memphis Theater Community will celebrate the best of the 2008-’09 season and raise a toast to actor/director, and recently retired University of Memphis theater professor Joanna “Josie” Helming when she receives the Eugart Yerian Award for Lifetime Achievement at the 26th annual Ostrander Awards. Helming was recruited to do her graduate studies in Memphis by Keith Kennedy, who founded the U of M’s Department of Theatre & Dance. She finished her MA in 1967 and became cornerstone of the U of M’s performance faculty.

On Sunday, August 30 the Memphis Theater Community will celebrate the best of the 2008-’09 season and raise a toast to actor/director, and recently retired University of Memphis theater professor Joanna “Josie” Helming when she receives the Eugart Yerian Award for Lifetime Achievement at the 26th annual Ostrander Awards. Helming was recruited to do her graduate studies in Memphis by Keith Kennedy, who founded the U of M’s Department of Theatre & Dance. She finished her MA in 1967 and became cornerstone of the U of M’s performance faculty.

Now, without much ado, here are the nominees for this year’s Ostrander awards…

Pictured: Josie Helming in Candida

Arrow Rock Lyceum, 1973

Mayor Herenton’s Last Day

On his last official day in office, Mayor Willie Herenton has scheduled a 2:00 p.m. press conference. Jackson Baker and other Flyer writers will be on hand. Watch this space for developments.

Meanwhile, you can scroll down and check out the Flyer blogs.

The New York Times has a story up on Cybill Shepherd, a hometowner who’s earned favored-celebrity status from Memphians after four decades in the public eye.

The New York Times has a story up on Cybill Shepherd, a hometowner who’s earned favored-celebrity status from Memphians after four decades in the public eye.

Margy Rochlin’s story starts, “The first time Cybill Shepherd appeared on a talk show was on The Tonight Show back in 1968. At the time she was a radiant 18-year-old from Memphis with a confrontational gaze who owned the title Model of the Year. ‘I could barely say a word,’ she said. ‘All I could do was say ‘Yes’ and look terrified.’”

Look for more Cybill in the future; as soon as this weekend, in fact, with Mrs. Washington Goes to Smith, which airs on the Hallmark Channel Saturday at 8 p.m.

She’ll also have a recurring role on Eastwick, an ABC show based on The Witches of Eastwick — you remember that, right? — that drops in September.

Midtown Water Woes

When city officials sought to reassure Midtowners that they wouldn’t notice a proposed 18-foot storm-water detention basin in Overton Park, they cited a similar project at Christian Brothers University.

But that detention basin has already caught the eye — and nose — of local residents. Mary Cashiola reports.

Unless yet another “Herenton shock” has occurred between the writing

of these words on Tuesday and the mayor’s scheduled leave-taking from

his duties on Thursday, the city of Memphis is finally about to enter

onto new and uncharted paths. It has long been presumed by the political

cognoscenti that Shelby County mayor A C Wharton — conciliatory

where Herenton is challenging; smooth where the outgoing Memphis mayor

has been peremptory — will accede to the job of city mayor. But

we have been through multiple surprises of late, and we’re not about to

take anything for granted.

The special mayoral election, certified by the City Council and

scheduled by the Election Commission, will take place on October 27th.

We’ll know who wins it when they’re finished counting the votes —

and not until — although there is reason to believe that Wharton

may have ranked prohibitively high in the poll that city councilman and

erstwhile mayoral prospect Jim Strickland recently commissioned, only

to decide against running upon receipt of it.

In summing up the 18 years of Mayor Herenton, it would be unfair to

judge the man only, or even mainly, by the conflict-of-interest

questions that have swirled up around him in recent years, or by the

increasing cronyism of his administration, or by his manifest boredom

with his job, or even by his ominous evocations of the race issue as he

revs up for an apparent run against 9th District congressman Steve

Cohen. The word “racist” as an epithet to describe his critics surfaced

only last week, when the mayor chose to be offended by public

questioning of his on-again, off-again timetable for leaving, so we

fear we shall hear it again as a counter to all sorts of future

questions.

Yet this is also the man who provided a reasonably seamless

transition in 1991 between all the years of white-dominated, even

segregated, city government that preceded him and the generation of

slow but real racial accommodation that has followed. Yes, there has

been “white flight” (and middle-class black flight, as well), but

personal and professional relationships across the old racial barrier

have multiplied since 1991, and Herenton is entitled to some credit for

that — as he certainly is for his vaunted conversion of

dilapidated public housing into some of the showcase projects that now

dot the city’s landscape.

In other words, things could have been a lot worse. We at the

Flyer named Mayor Herenton “Man of the Year” for 1997 for his

resourceful, even heroic defense of the city’s growth prerogatives

against the encroachments of the infamous “toy town” act that would

have balkanized Shelby County and hemmed in Memphis. Without Herenton’s

pressing the issue, the act might never have been tested by the state

Supreme Court and declared unconstitutional.

In any case, we wish ex-Mayor Herenton (though not necessarily

candidate Herenton) well as he enters the next phase of his life and

career. He has been a titanic influence in our affairs, and his

reputation can only grow if he comports himself with dignity — or

sadly sink if he does not.

Two Testaments

Hip-hop has produced more momentous artists than De La Soul. Run-DMC, Public Enemy, Eric B. & Rakim, Notorious B.I.G., Outkast, and a few others have a greater claim to the genre’s Mt. Rushmore. But in a culture so far short on longevity and mutability, I know of no other hip-hop artists whose peaks are more than a decade apart and who have had as much to say to the music’s fans — once referred to as the hip-hop generation — about living a rewarding life.

As Long Island teenagers making their debut with the precocious epic

3 Feet High and Rising, this trio — Kelvin “Posdnuos”

Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Mase” Mason

— bravely tested hip-hop’s cultural boundaries, burrowing deeply

into their own idiosyncratic personalities. Later, as thirtysomething

fathers on the deep and subtle AOI: Bionix, they crafted the

most convincing argument yet for what hip-hop as stable grown folks’

music might sound like.

“Sony Walkmans keep us moving/De La Soul can help us

breathe.”

— “Tread Water,” 3 Feet High and

Rising

Released in 1989, 3 Feet High and Rising spearheaded a

hip-hop movement known as the Native Tongues, a loose affiliation (or,

in Tongues parlance, a tribe) of artists such as A Tribe Called Quest,

Jungle Brothers, and Queen Latifah united by a philosophy of

“Afrohumanism” and a playful sense of sonic exploration. The Native

Tongues offered both a middle-class alternative to a form born in the

New York City streets and housing projects and a gentler alternative

within a genre then divided by the political militance of Public Enemy

on the East Coast and the gangsta aesthetic of N.W.A. on the West

Coast.

De La’s debut was a commercial hit and a relative critical smash,

winning 1989’s Village Voice “Pazz and Jop” national critics

poll, becoming the first teen winner and first debut-album winner since

the Sex Pistols. But even then some found it too slight to be a Great

Album, its full-fledged songs interrupted by recurring skits (a

practice it launched, for better or worse), esoteric jokes, and other

aural experiments, and its perspective too unreadable and

navel-gazing.

Fans dubbed it “the hip-hop Sgt. Pepper’s,” but in retrospect

“the hip-hop White Album” is probably a more apt Beatles

comparison. More audacious and more definitive than anything else to

come out of the Native Tongues crew, it’s a sprawling 24-track

invitation to an unknown world, filled with in-group solidarity (“The

Magic Number,” “Me, Myself, and I”), social commentary (“Ghetto Thang,”

“Say No Go”), inspired DJ cut-and-paste (“Cool Breeze on the Rocks”),

Aesop-like fables (“Tread Water”), and total weirdness (“Transmitting

Live From Mars,” 66 seconds of a scratchy French spoken-word record

over a Turtles sample).

It’s an album that contains both hip-hop’s first convincing love

song with “Eye Know” (right, LL Cool J’s “I Need Love” came first, but

he just wanted to get in your pants) and still the genre’s healthiest

sex song with the posse cut “Buddy.” And despite its teen-oriented

self-absorption, it has a fierce spirit. The first rapped verse on the

record, courtesy of 19-year-old Posdnuos: “Difficult preaching is

Posdnuos’ pleasure/Pleasure and preaching starts in the heart.”

With its “D.A.I.S.Y. Age” rhetoric (which stands for “Da Inner

Sound, Y’all” — don’t laugh), Day-Glo color schemes, private

lingo, unexpected references (stray lyrics about Fred Astaire and

Waiting for Godot), and inscrutable in-jokes (“Posdnuos has a

lot of dandruff”), 3 Feet High and Rising was the sound of

creative teenagers energized by their own brains. As much as indie-rock

kings-in-waiting Pavement, who emerged soon after, these were modestly

privileged suburban bohemians turning their surfeit of leisure time and

their overactive intellects into something familiar yet totally new,

its verbal imagination actually topped by its sonic imagination.

Two years earlier, fellow Long Islander Rakim — as

culturally conservative as De La Soul were radical — had made a

claim for the genre: “Even if it’s jazz or the quiet storm/I hook a

beat up/Convert it into hip-hop form.” It’s a classic lyric, one that

announced the genre’s voracious musical appetite. But Rakim couldn’t

think past mainstream African-American forms. De La, inspired by George

Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic and partnered with sampling genius

Prince Paul, took Rakim’s manifesto and added to the list Hall &

Oates, Steely Dan, Johnny Cash, Schoolhouse Rock, and a

French-language instructional record, just for starters.

Underground mix-masters like Double Dee & Steinksi were earlier

to the game, and the Beastie Boys would double-down on De La’s

achievement later the same year with Paul’s Boutique, but more

than anything else, 3 Feet High and Rising expanded hip-hop’s

sonic vocabulary.

As insistent as the trio had been initially to confront hip-hop’s

cultural boundaries (perhaps captured best in the comically put-upon

“Me, Myself, and I” video), they did succumb to peer pressure,

recording the fed-up defense to a stupid recurring description, “Ain’t

Hip To Be Labeled a Hippie,” and then following up 3 Feet with

the self-conscious and self-negating De La Soul Is Dead.

But 3 Feet‘s influence won out. The sonic message was that

absolutely anything could be turned into hip-hop. But the personal

message was that hip-hop could be anyone’s vehicle for self-expression,

a message later embraced by white trailer-park residents (Eminem),

mixed-race Midwesterners (Atmosphere), nice middle-class white girls

(Northern State), Third World survivors (M.I.A., K’ Naan), and lots of

other people with something to say and a beat to say it over.

“No need to spit a cipher to show you I’m a lifer in rap/I

cultivate moves larger than that.”

— “Bionix,” AOI: Bionix

3 Feet High and Rising‘s sonic fragmentation is generational

but also partly a production of youth. Feeling creakier on the wrong

side of 30, the band pursued a steadier groove on their Art Official

Intelligence (AOI) records: 2000’s Mosaic Thump and

2001’s better Bionix (the latter getting my vote as the past

decade’s most overlooked hip-hop album). Where 3 Feet was bumpy,

the AOI records are smooth. Where 3 Feet was clever and

cryptic, the AOI records are smarter and more plainspoken.

What the trio lost in youthful verve they made up for with a

consistently rewarding musical vision on their second career peak.

Rather than the Prince Paul-organized bricolage and jokiness of 3

Feet High and Rising, here is hip-hop as the ultimate adult

R&B, without the confrontational assault or showy party vibe of

most contemporary mainstream hip-hop or the spare beats of the

underground. Rather, De La’s AOI records luxuriate in the

sturdy, comfortable, and soulful — groove music for

stay-at-homes. This music doesn’t grab you, but it deepens over

time.

And it’s no accident that the more limited sources but more

consistent groove connects more fully to the African-American musical

tradition. After flying their freak-flag as kids, this later music

embodied the black middle-class experience they were living. Even the

skits on Bionix (“Rev. Do Good”) tap into an African-American

iconography that might have felt limiting as teenagers.

With AOI: Bionix, the group united verbal concept with the

music’s grasp for the eternal. This was an album about growing up

without giving out. Its most compelling moment comes on the concluding

“Trying People,” one of the first pop-music acknowledgements of 9/11

outside of tribute-song rush jobs. The song is directed at hip-hop’s

younger generation, with Dave (long since dropping his old “Trugoy”

moniker) rapping, “You see, young minds are now made of armor/I’m

trying to pop a hole in your Yankee cap/Absorb me/The skies over your

head ain’t safe no more/And hip-hop ain’t your home.”

Once obsessed with making music in their bedrooms, the group was now

focused on a different set of priorities: “Got fans around the

world/But my girl’s not one of them,” Posdnous raps on the same song.

“And my relationship’s a big question/’Cause my career’s a clear

hindrance to her progression/Says she needs a man and her kids need a

father/And I’m not at all ready to hear her say ‘don’t bother.'”

This central conceit is explored all over the record. The opening

scene-setter, “Bionix,” features lyrics such as, “I don’t ball too

much, ya dig/I got a ball and chain at the crib who want my ass at

home.” The charming lead single, “Baby Phat,” is the middle-aged answer

to Sir Mix-a-Lot’s “Baby Got Back”: “Your shape’s not what I dig/It’s

you … You ain’t in this alone/I got a tummy too/Just let me watch

your weight/Don’t let it trouble you.” On “Simply,” they search for a

place to have fun without young “thugs” ruining everything, and on

“Watch Out,” they make romance by proposing a joint account.

The record’s decorum breaks down toward the end with the sexed-up

“Pawn Star” (which should surprise no one who remembers 3 Feet High

and Rising‘s “De La Orgie”) and the funny, conflicted marijuana

meditation “Peer Pressure” (with Cypress Hill’s B-Real). But this

detour is needed confirmation that adulthood doesn’t have to equal

stodgy.

Hip-hop hasn’t yet proven to be a form with the personal longevity

of blues, country, or even rock. But after saying more about both

teendom and responsible adulthood than anyone in the so-called hip-hop

nation, one hopes De La Soul can stay interested long enough to pull

hip-hop into the uncharted territory of middle age.

No Exit

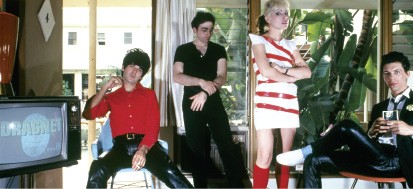

As the name of Blondie’s 1999 comeback album No Exit implies, there seems to be no end for

these new-wave legends.

Debbie Harry & Co. (pictured) hit the road this summer with

rocker Pat Benatar and late-’90s hard-rock girl band the Donnas. The

tour stops in Memphis for a show at Mud Island on Saturday, August 1st.

Blondie drummer Clem Burke took a few minutes from the road to speak to

the Flyer about Blondie’s past and future.

Flyer: Rap music is a huge force in Memphis. But

didn’t Blondie pioneer rap with “Rapture” in 1981?

Clem Burke: I’m sure it was the first hit rap song. The

melody to the song was written by the band, while a lot of rap music at

the time sampled other hit songs. But we wrote our own hit song and put

the rap in, and that’s kind of the template today for modern-day rap,

like with Kanye West.

What’s your favorite Blondie song?

It’s difficult to

choose. But my favorite record is Autoamerican, which has

“Rapture” on it. When we delivered that record to the record company,

they told us it didn’t have any hits, and it ended up having two

number-ones, “The Tide Is High” and “Rapture.”

Is there a new Blondie album in the works?

We hope to have a new record out by the middle of next year. One of

the reasons we went on tour now is to get the band up and running.

We’ll go into the studio afterward and record some new work. We’ve

recorded a few new songs. We’ll be playing one or two when the mood

strikes us during the show.

Amazing Race

The Memphis Riverfront International Championship Regatta: That’s

quite a mouthful. But the title befits the event, which boasts an

extensive list of attractions and hopes to draw a sizable crowd to Tom

Lee Park July 31st through August 2nd. The regatta is not only the

first in Memphis, it is the first on the Mighty Mississippi — a

stretch of river that boat racers have been clamoring to tackle for

years.

Jesse Briggs, event coordinator, says this race will make Memphis a

major player in the powerboat arena. Whereas high-speed boat races

usually bring in around 20 boats, Briggs expects to have 40 boats

contending for the championship. Powerboat contestants will race around

a rectangular track, reaching speeds of up to 125 mph. Between races,

the waterway is cleared to accommodate passing barges, something Briggs

touts as a sort of slow-paced interlude. In addition to high-speed boat

races, the regatta will feature live music, food vendors, kiddie park,

kayak races, and jet-ski acrobatics. Radio station Rock 103 is covering

the event, along with Fox Sports South.

This is the inaugural race of what is slated to be a yearly event.

“We have a five-year contract with the APR Powerboat Super League to

make their championship cup destination the great city of Memphis, with

an option for an additional five years,” Briggs explains.

The festivities begin each day at 10 a.m. and end at 7 p.m. After

the races on Saturday, head over to Primetime Sports Bar and Grill for

an after-party with the drivers, V.I.P.s, and sponsors. And as for

tickets? “The event is free,” Briggs says. “It’s what we like to call

financially friendly.”

Points of View

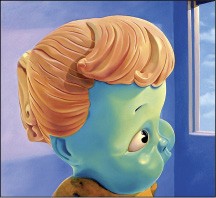

The current exhibition at the Dixon’s Mallory and Wurtzburger

Galleries, titled simply “Beth Edwards,” is the most complete gathering

to date of Edwards’ emotionally complex portraits of the

mid-20th-century American dream of owning shiny new convertibles and

ranch-style homes furnished with Danish modern divans, potted plants,

and modern artworks, or, if original work was out of the question, good

reproductions.

Instead of human models, Edwards uses vintage rubber toys as

stand-ins for the proud homeowners. In Happy Day, an

anthropomorphic mouse with a frozen smile and huge lidless eyes stands

proudly in his spic and span living room. The shape of his moist black

nose is repeated in the fractured face of Picasso’s portrait of his

mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. In Good Morning,

another happy homeowner — in this case, a beautiful, young golden

retriever — is backdropped by a royal-blue divan and Philip

Guston’s painting of a huge pile of worn-out footwear (horses and

humans), an allusion perhaps to the labor required to build beautiful

homes for the well-heeled.

Pinkney Herbert’s Delta Series L

The glossy surfaces, controversial masterworks (that elicited

outrage when they were first unveiled), and the frozen-faced dolls that

populate Edwards’ “happy paintings” suggest the search for happiness is

a slippery slope layered with complex feelings that can exhilarate or

undo us.

Like Edward Hopper, Edwards handles color with such mastery that her

artwork achieves a kind of transcendence. The iridescent-green baby

doll in Annunciation looks out a window at a blue sky feathered

with clouds. The figure’s chubby cheeks and huge brow are framed inside

a Hopperesque square of lavender light.

Ultimately, Edwards’ art is about the power of light to consume all

color and form, to absorb all paradox and pain into visions of

paradise. Edwards understands Hopper’s desire to do nothing but paint

light on the side of a house.

Through September 6th

Pinkney Herbert’s Jig

In David Lusk Gallery’s current show, “Floating World,” Pinkney

Herbert’s paintings no longer blast our point of view across

30-square-foot surfaces. Neither are they as spare as the paintings in

Herbert’s 2007 exhibition, a show in which softly curving lines,

wide-open spaces, and the quiet authority of works like Wing

seem inspired as much by Zen Buddhism as 20th-century

abstraction.

Instead, Herbert’s “Floating World” works are by turns fluid,

syncopated, celebratory. Their open and buoyant compositions, inspired

in part by the elegant woodblock prints of Japan’s Edo period

(1603-1868), invite us to take our time, to explore their textures,

colors, and shapes, and to realize that, though they are more subdued

than Herbert’s explosive earlier work, these paintings are as evocative

and original as any in his long and varied career.

Beth Edwards’ Annunciation

In “Floating World,” we feel the rhythms of New York as well as

Memphis, the two cities where Herbert lives and paints. Deep-red spiked

flowers surrounded by scumbled umber at the heart of Herbert’s pastel

on paper Delta Series L look as rich as Mississippi bottomlands,

as fertile as the Southern soul. In Buoy, a figure eight

accented with red-and-yellow lozenges wafts on air currents that twist

in unexpected directions like New York City’s improvisational jazz.

A cartoon-like hand with triple-jointed fingers and attenuated wrist

lies at the center of the nearly 6-foot-tall painting Jig. We

can almost hear the sound of one hand clapping in this crisp-edged,

bright-orange shape backdropped by a wash of pure yellow.

Two years after his last show, Herbert returns to David Lusk with

his sense of humor intact, with a new zest for life, with a mindset

similar to what 17th-century Japanese novelist Asi Ryoi described in

Tales of the Floating World as “refusing to be disheartened,”

turning one’s attention to the pleasures of the beautiful, impermanent

world.