It feels cool to be in Memphis,” a young Japanese man says, gazing out the window of the soon-to-be-demolished Arcade Hotel.

This scene occurs in Jim Jarmusch’s 1989 film Mystery Train, and it’s a common sentiment — conveyed if not always directly expressed — in cultural works made in or about the city ever since. It’s the ideal that animates the current Broadway hit musical Memphis but also two filmed representations of the city that have arrived this month within a week of each other.

One is Mystery Train itself, Jarmusch’s critically acclaimed indie flick and landmark work of made-in-Memphis cinema, which was re-released in a Criterion Collection DVD and Blu-Ray version on June 15th. The Criterion release is a new, gorgeous high-definition digital transfer that was supervised and approved by Jarmusch. It comes with a remastered soundtrack and loads of great supplementary material, including a brief documentary on the Memphis locations hosted by Shangri-La Projects’ Sherman Willmott (who served as a production assistant on the original film), Novella Smith Arnold (who was the local casting director), and musician Marvell Thomas and Judge D’Army Bailey (who had small on-screen roles). The other is Memphis Beat, a set-in-Memphis but largely filmed-in-Louisiana television series on the TNT cable network, which debuted June 22nd.

More than perhaps any other big or little screen productions made and/or set in Memphis, Mystery Train and Memphis Beat are essentially — if not totally — about Memphis, not only as a place but perhaps even more as an idea. Both are affectionate outsider’s takes on the city, if widely divergent in approach and familiarity. But each seeks to make the city itself a key character.

Though these two works of Memphilia are separated by an aesthetic gulf that makes comparison almost unfair to Memphis Beat, the more interesting and instructive differences between the two are rooted not in quality but in proximity (or lack thereof) and the changes within the city they each purport to capture.

Filmed in Memphis in the summer of 1988, Mystery Train is a triptych of interconnected stories that depict the city through the eyes of three types of outsiders: tourist, stranded traveler, and immigrant. The first section follows a couple of Japanese teens on a pilgrimage to see Sun Studio and Graceland. The second depicts an Italian widow with a local layover. The third tracks a trio of friends, including a downbeat Brit (Joe Strummer), across a wild, reckless night.

The three stories are told separately but are happening at the same time, with a series of recurring audio elements — a bypassing train, Elvis’ “Blue Moon” on the radio, a gunshot — establishing the temporal connectedness. And each set of protagonists ends up taking a room at the Arcade Hotel, where the desk is manned by a superb, deadpan comic team of Cinque Lee (Spike’s brother) and R&B legend Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

On the surface, Mystery Train might not appear to be much of an advertisement for the city. Two brief airport scenes and the Sun Studio tour might be the only moments in the film in which Memphis doesn’t appear seedy, blighted, or overgrown. Mystery Train’s Memphis is a land of decrepit movie theaters, rundown hotels, rusted liquor stores, and dimly lit dive bars.

Much of the film takes place at the corner of South Main and what was then Calhoun (now G.E. Patterson). At the time, this was not the part of town that civic boosters wanted showcased.

Memphis & Shelby County Film commissioner Linn Sitler, for whom Mystery Train was a first major client, remembers charging then mayor’s aide Alonzo Wood with escorting Jarmusch around town to scout locations.

“[Wood] kept trying to steer him to the more upscale parts of town,” Sitler says. “We didn’t know at the time, because we weren’t familiar with Jarmusch, that it was his style to film the more rundown parts of town.”

The Arcade Restaurant, which is showcased in the film’s middle section, looked much as it does today. But the rest of the intersection was in rough shape. The Arcade Hotel was so forlorn that it was only safe to shoot scenes in the lobby. The building was demolished the following year.

Sitler, who says she got concerned calls from a liaison with the city mayor’s office about where the shoot was occurring, remembers a sheriff’s deputy having to clear hookers from the streets each night before filming.

That area of South Main has cleaned up considerably in the years since Mystery Train, but it has retained its character. It’s now arguably the most filmed part of the city, but the intersection’s cinematic life started with Jarmusch, as a plaque now there in the film’s honor so notes. Sitler gives the film some credit for the revitalization of the South Main district.

“I think that it gave [South Main] a cachet, a hip and cool cachet,” Sitler says.

When Mystery Train wanders away from Main and Calhoun, the picture doesn’t get much prettier. Mystery Train was filmed “around the nadir of Memphis and its self-esteem,” Willmott says in the accompanying locations documentary. Jarmusch himself, in a new audio Q&A on the disc, says, “I did look for locations that were somewhat, I dunno, bleak in a way or somewhat barren. But Memphis really felt like that. Memphis pretty much felt like a ghost town.”

Mystery Train is about a “Memphis” that was forgotten, a stranger in its own hometown. And Jarmusch’s film is an excavation. A cultural legacy seeps through, abandoned but holding on, down but not out. Rufus Thomas is hanging around the train station. Three characters ride by the boarded-up remains of the Stax location on McLemore, a hand-scrawled “Stax” across the white wood facade the only recognition of past glories, a barren rebuke to the city.

“It was like that when we filmed,” Jarmusch remembers on the audio Q&A. “We didn’t graffiti ‘Stax’ on there when we filmed. Someone else had, but that was the only thing identifying it. There was no idea of preserving it. The building was torn down maybe a year after we filmed.”

There is a documentary aspect now to Mystery Train, a rare filmed record of a time when Memphis seemed to have forgotten what it had. This is Memphis before the full reflowering of Beale Street as a tourist center (the lone Beale scene in the film is a depopulated daytime stroll in front of A. Schwab), the opening of the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel, the building of the Stax Music Academy and Museum of American Soul Music on the old Stax site. Sun, captured here, had re-opened only a few years earlier.

But it’s also a reminder of how much hasn’t changed: The derelict movie theater at the corner of Lamar and Felix that makes such a striking backdrop in a couple of shots still stands empty, crumbling. And downtown renewal hasn’t touched other Mystery Train locations, among them a lonesome stretch of Vance.

If Mystery Train is a vital document of what Memphis was in 1988, it’s not a complete picture. A few years later, The Firm would depict a different side of Memphis: elegant downtown law offices, comfortable East Memphis homes, Peabody rooftop parties.

The idea of Memphis in Memphis Beat is an unwitting reflection of what happened when the world of The Firm began to acknowledge and embrace the world of Mystery Train: Culture finally preserved and honored, but also, at times, smoothed out and commodified. For better or worse, Memphis Beat, which will broadcast Tuesday nights at 9 p.m. on TNT, is very much a “Home of the Blues and the Birthplace of Rock-and-Roll” version of Memphis.

The series, which debuted this week for a 10-episode first-season run, is a personality-driven police procedural about a music-loving Memphis detective, Dwight Hendricks (Jason Lee, perhaps best known as the star of the recent series My Name Is Earl). There’s a different case introduced and solved each week but with character arcs that will build across episodes. Lee’s Dwight is pitted against a strict but accomplished superior, played by veteran Alfre Woodard. Hustle & Flow‘s DJ Qualls adds color as a Barney Fife-esque uniformed cop. The familiar format is similar to that of TNT’s biggest original-series hit, The Closer.

In the pilot, written by show co-creators Joshua Harto and Liz W. Garcia, Dwight is charged with investigating the beating and financial exploitation of an elderly lady who turns out to be a (fictional) retired disc jockey from the (real) Memphis radio station WHER (a Sam Phillips experiment using an all-female staff). Amid the procedural plot, Memphis Beat establishes Dwight as a charismatic but competent cop who loves Elvis, his mama, and hot biscuits.

There are similar visual references in the two works: Japanese tourists with rockabilly haircuts, dark blues bars, and well-worn concrete convenience stores. But Memphis Beat is a more optimistic and less prickly look at Memphis culture than Mystery Train.

You can see this perhaps most clearly in the divergent treatments of Elvis Presley. Mystery Train is conflicted about the so-called King. It opens with Elvis’ classic Sun version of the song that provides the film’s title, but it very pointedly closes with the original Junior Parker version. The young Japanese woman loves Elvis, building a scrapbook in his honor, but her boyfriend resists his canonization, and an argument ensues over who was better, Presley or Carl Perkins.

The Joe Strummer character is dubbed “Elvis” by others in the film, a tag he hates, and his resentment boils over when an oil portrait of Presley stares down at him from an Arcade Hotel wall.

Jarmusch’s insistence on Memphis culture beyond Elvis is reflected in a sharp-eared connoisseur’s soundtrack that digs beyond the familiar hits. In this world, the favored Elvis tune is his eerie, beautiful take on “Blue Moon,” a Sun obscurity.

Memphis Beat, by contrast, opens with the achingly familiar, ersatz Sun of “Heartbreak Hotel” and never once — at least in the pilot — questions the dominance of Elvis in Memphis music culture. Each episode is named after an Elvis song (the pilot is “That’s All Right, Mama”; next week’s episode is “Love Me Tender”) and where Strummer’s “Elvis” resists the comparison, Lee’s character welcomes it, professing his obsession with Presley (“It was like he was saying everything I was feeling, just in the sound of his voice”) and closing the pilot by performing “If I Can Dream,” presumably at a Beale blues bar.

If Mystery Train reflected a Memphis where the cultural legacy was neglected, inspiring Jarmusch to dig deep, Memphis Beat reflects the trade-off that comes with renewed civic attention: The history is more embraced, but the hits rise to the fore and the compelling kinks are sometimes ironed out.

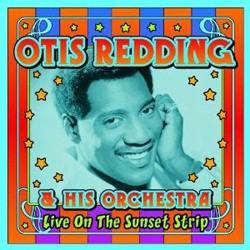

But if Memphis Beat seems to be more of a “greatest hits” version of the Memphis story, its commitment to the city’s music still seems both sincere and significant. And the soundtrack is still awesome. In addition to the copious Elvis, the pilot is packed with Memphis music: Booker T. & the MGs, Rufus Thomas, Dusty Springfield, Albert King, and Otis Redding covering Sam Cooke. Memphis Beat show runner Scott Kaufer promises more to come.

“The music in Memphis is a major component [of the series],” Kaufer says. “And not only because Dwight likes to sing, particularly Elvis songs. He also loves the varied music over many decades that’s come out of that place. Going forward, in the score of each episode, there’s an amazing sampling of Memphis music from all genres.”

While Mystery Train represents — along with the same year’s more high-profile but artistically inferior Great Balls of Fire — the beginning of Memphis as a fertile site of film production, Memphis Beat represents what, at least for the moment, seems to be a waning period.

Memphis Beat joins The Blind Side and Craig Brewer’s upcoming Footloose in forming a trio of major film/television projects set in the Memphis area but filmed elsewhere for financial reasons.

The calculus of film production has changed in recent years as states have begun to compete for projects using more and more lucrative tax incentive packages to lure Hollywood productions. Tennessee has been losing out to Louisiana (Memphis Beat) and Georgia (The Blind Side and Footloose), states that have more liberal incentive policies.

“If you’re a film commissioner anywhere now and you’re talking to a producer about a project, the conversation no longer starts with ‘Tell me about your locations.’ It starts with ‘Tell me about your incentives.’ And if you don’t have a good answer for that, the conversation ends,” Brewer says.

Tennessee’s incentives package — and its implementation — has forced Brewer’s $25 million Footloose remake to Georgia, where it’s scheduled to begin shooting in August. Brewer’s next project, the $55 million Mother Trucker, will follow with a Georgia shoot — possibly next summer — for the same reasons.

Brewer, clearly frustrated by this, points out that, over the past year, the number of major Tennessee-set productions has been cut in half, with most of those projects landing in Georgia or Louisiana instead. While the short-term economic costs and benefits of more aggressive incentives packages is up for debate, the long-term damage in regard to developing a local and regional film industry is clear.

But aside from the economic and infrastructure concerns, is there also a cost in how the region is represented in works filmed elsewhere? Certainly, a disconnect between setting and location is more norm than exception in American film and television. And location shooting is no guarantee of verisimilitude, as anyone who remembers Mary Kay Place’s character threatening to “throw [that] damn bottle across Union Street” in The Rainmaker can attest.

But there does seem to be a cost in trying to create a version of Memphis from two states away. Memphis Beat conducted a two-day second-unit shoot in Memphis, which results in frequent cutaway shots of familiar Memphis locations. But all the main shooting was done in Louisiana. When Qualls’ beat cop references snacking on a catfish po-boy early on in the pilot, it doesn’t raise an eyebrow — not our signature sandwich, but common enough. But when, soon after, Lee’s detective commands his charges to canvass a “ward,” then later visits with an underworld leader in what appears to be a Haitian community, the New Orleans location seems to be bleeding into the content.

“It is a challenge,” Kaufer says about producing the Memphis-set series in Louisiana. “Memphis is not an afterthought. [The show’s creators] fell in love with the city and tried to create a piece where the city is a character as well. It would be much easier if we could just turn a camera on and everything that fills the frame is our subject matter. Instead, a great deal of care has to be given to picking locations that as nearly as possible give the ethos of Memphis. It’s never going to be a perfect match, but I think our folks down there have done an awfully good job of trying to come up with a credible substitute.”

“Of course, we wanted them to shoot it here, and the writers and the whole creative team did as well,” says Sitler, who has worked closely with the series’ producers. “We were really disappointed. The executives told me they were on such a tight budget that they needed to go where the incentives were best and where they were used to shooting. It’s just sad that they’re not shooting here. With all the billboards and the ads, it’s like a knife in my heart.”

Though second-unit photography and Louisiana approximations will have to do for the first season, series star Lee has been vocal about wanting to shoot some scenes in Memphis, and Kaufer says that’s in the plans.

“It’s something we had hoped to do this time around,” Kaufer says. “The production steamroller wouldn’t allow for it in this early pod of episodes. But if we’re lucky enough to get additional orders, you can count on us being down there and doing additional shooting in Memphis.”

Memphis Beat may not yet — or ever — be the television series Memphis wants or deserves, but it’s the television series Memphis has gotten, and skeptical locals might want to give it a little leash. Television series have a way of finding their footing over time, so the mundane procedural aspects and loving but limited (and often clunky) Memphis-isms of the pilot episode shouldn’t be considered a final word on what Memphis Beat can become.

Certainly, it’s getting a chance. Memphis Beat is being pushed hard by TNT and is ubiquitous in the city, with a billboard promoting the show greeting those leaving the airport and a massive sign covering the side of one Peabody Place parking garage.

Sadly, but not surprisingly, the attention paid to Mystery Train‘s re-release seems to be mirroring the work’s subterranean, subcultural creation. Though a signature work of Memphis art and a crucially important catalyst in the rebirth of the Memphis brand that’s made the likes of Memphis Beat possible, the new Mystery Train wasn’t being stocked by any of the four national chain retailers in town I contacted the day after its release. But make no mistake: Mystery Train should be a part of any Memphian’s cultural vocabulary.