The Battle of Gray’s Creek: It sounds like a Civil War story. Consolidation, school system merger, financial obligations of municipalities, and annexations. It sounds like a graduate course in public policy or a stimulus bill for lawyers.

Actually, it’s the Memphis news agenda for the last two years. And, this week, suburban lawmakers are threatening to undo a 1999 annexation deal, and Mayor A C Wharton and the Memphis City Council are up in arms.

Don’t you miss the narrative plot and drama of Tennessee Waltz? And the finality? I do. Trials end. There are bribes and mysteries. Annexations go on for years. There are consultants, planning teams, and 100-page studies.

A short history lesson is in order.

“The annexation of surrounding areas has long been a significant component in the racial politics of Memphis,” wrote Rhodes College political scientists Marcus Pohlmann and Michael Kirby in their 1996 book Racial Politics at the Crossroads.

Memphis annexed Frayser in 1958, Parkway Village in 1965, Whitehaven in 1969, Raleigh in the 1970s, and Cordova and Hickory Hill in the 1990s. All of them were majority white at the time the annexations began, and their completion helped preserve a white voting majority in the city until the 1990s.

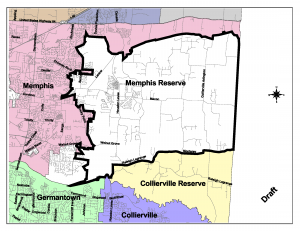

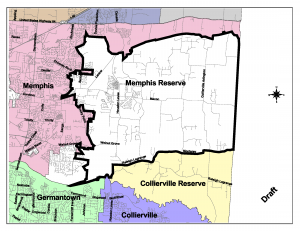

In 1999, Memphis and the suburban municipalities in Shelby County signed an annexation reserve agreement, divvying up territory like Indian tribes splitting ancestral hunting lands.

“We were the only county in Tennessee that had to develop an annexation reserve area plan,” said Louise Mercuro, former deputy division director of the Office of Planning and Development. “I wrote the Shelby County plan and the Memphis plan.”

The agreement was hailed by then-mayors Willie Herenton and Jim Rout as “historic” and a “backbone for the growth plans” for the next two decades.

Not quite. After 2000, annexation pretty much ran off the rails. The city council took aim at densely populated southeast Shelby County just about the time the housing market crashed in 2007. Developers pleaded to be left out. Maps were redrawn. The annexation is pending. Memphis took in some commercial strips but not the residential areas of Southwind and Windyke, where property owners got a city tax holiday until 2013. Or Southwind High School, which remains a county school.

No matter how hard it tried for 50 years, Memphis could never catch up with white flight. Tens of thousands of people moved out of the city’s grasp to DeSoto County, Mississippi, or to Germantown, Bartlett, and Collierville. Between Census 2000 and Census 2010, the population of Memphis fell from 650,000 to 647,000. In 1970, before several big annexations, it was 624,000.

So which city is bigger? Memphis, St. Louis, or Atlanta? It’s a trick question. In land area, Memphis, at 315 square miles, is bigger than St. Louis and Atlanta put together (195 square miles). The people just keep slipping away.

The wedge of unannexed Shelby County between Bartlett and Germantown that is at issue is called the Gray’s Creek Basin. Around 1997, Memphis, after years of resistance, agreed to extend the city sewer into it, which opened it up to development. Suburban developer Cary Whitehead Jr. used to say “he who controls the sanitary sewer rules the world.” Mercuro says the area has more than 50,000 residents.

When the Memphis City Council meets this week, it will revisit annexation and the 1999 growth agreement. There will be some outrage, some speeches, and some unity among black and white council members and the mayor around the positives of local control and the negatives of state interference and racial politics. Memphis can possibly win the coming battle over the legality of the 1999 agreement and the efforts in Nashville to undermine it.

But it can’t win the war for the hearts, minds, tax dollars, and school-age children of suburbanites determined to live outside the Memphis city limits and send their children somewhere other than Memphis City Schools or the future Shelby County merged school system. That has been proven again and again.

The muni mayors and their friends in the General Assembly have their sights on unannexed populations on their borders, just as Memphis did for more than half a century. For Memphis, the name of the game used to be Capture the White Voters. For Bartlett, Collierville, and Germantown, the name of the game now is Capture the Children, to support their future school systems.

Where there’s a will there’s a way. Maybe not this year, maybe not 2013, but some day.