John Branston finds some strong parallels between 1973 and 2012 when it comes to Memphis and Shelby County schools.

Month: June 2012

Schools: Is It 1973 Again?

The short answer is “no” but there sure are some interesting parallels.

In 1973 and 1974, some 30,000 students left the Memphis public school system in white flight in reaction to court-ordered busing for integration. In 2013, some 30,000 students could leave the “unified” Shelby County schools to attend new municipal school systems, if the voters approve and the courts allow the establishment of such systems.

White flight cut the enrollment of MCS from 148,000 students to about 120,000 students. Five or six municipal school systems would cut the enrollment of the unified system from about 148,000 students to about 120,000 students.

A federal judge in Memphis is once again at the center of the story that is getting national as well as local attention. In 1973 it was Robert McRae — a Central High School graduate and Lyndon Johnson appointee who wore a red judicial robe and was capable of flashes of temper and impatience from the bench. In retirement, he joked that he was Central’s most famous graduate since Machine Gun Kelly. Now the judge of the hour is Samuel H. Mays, a White Station High School graduate and George H. W. Bush appointee whose low-key courtroom mannerisms are often as folksy and wry as they are wise.

Mays wrote last year’s order and consent decree on the schools merger and now faces a Shelby County Commission challenge to the scheduled August 2nd referendum on municipal schools. His ruling on “ripeness” last year invited such a challenge at a later date, and that time has come.

Mays, I believe, is the perfect person for the job. He graduated from White Station in 1966, smack in the middle of the one-grade-a-year desegregation plan that was scrapped in favor of busing. He is a graduate of Yale Law School in 1973, and had to have been aware of what was happening in his hometown and his high school alma mater. Most important, he has experience in the rough-and-tumble world of state politics as chief of staff for former Tennessee Gov. Don Sundquist.

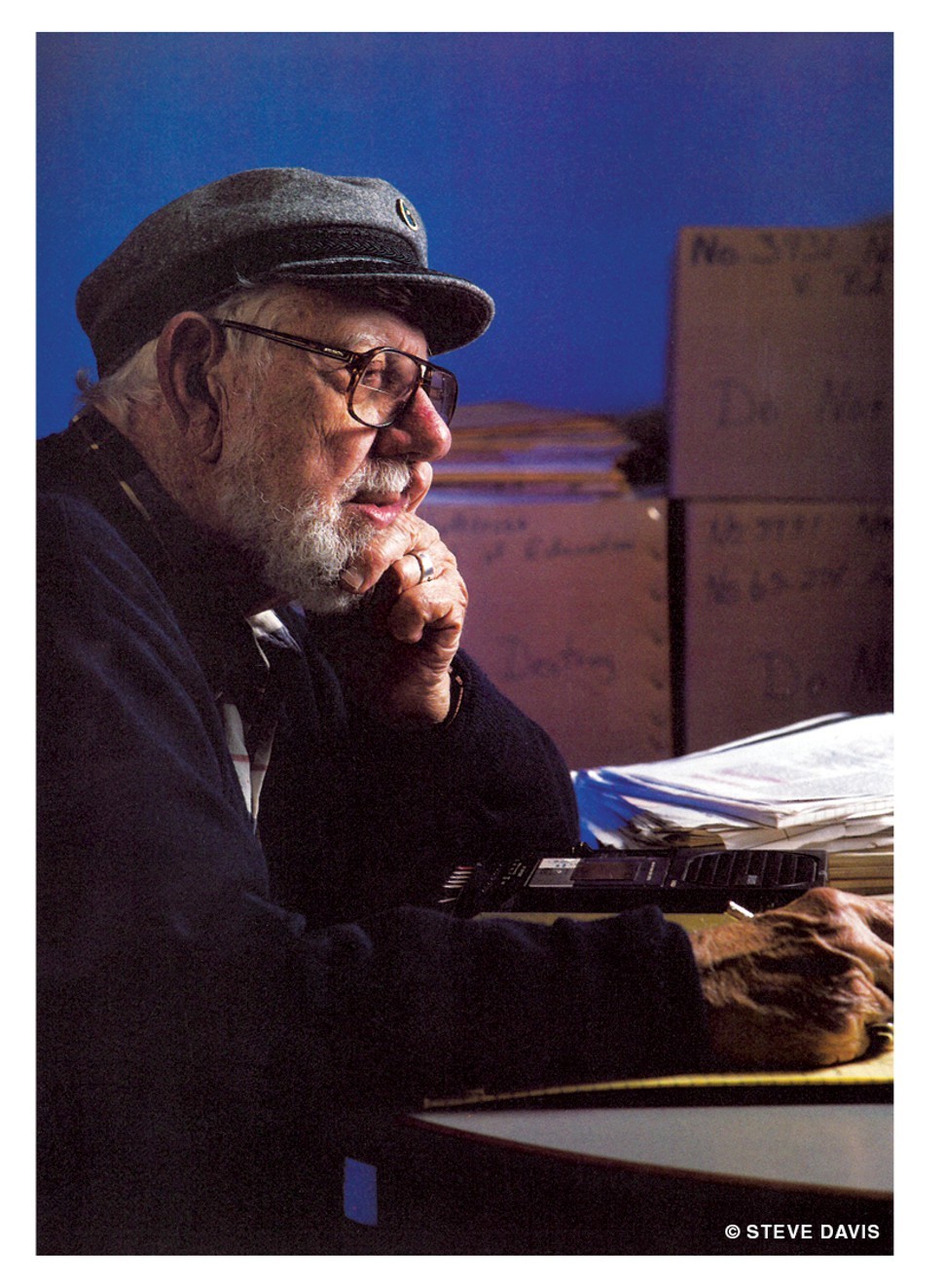

McRae kept a box of hate mail that he drew upon when completing his nine-part oral history for the Mississippi Valley Collection at the University of Memphis. I don’t know this for a fact, but I doubt that Mays gets much if any hate mail; he is rarely criticized in the thousands of online comments on schools stories I have seen.

I spent several hours interviewing McRae in his retirement. He was not a man to shirk a task, but he was a somewhat reluctant history maker and fully aware of the consequences of busing.

“I tried to stop with Plan A but the appeals court wouldn’t allow that,” he said in 1995. “I was disappointed in the reaction to Plan Z. But I had to keep a stiff upper lip because this [reaction] was an act of defiance. Still I was disappointed that we hadn’t come up with something that worked.

“No, I wouldn’t do it any other way. I am convinced there was nobody who could have settled this the way the parties were opposed. Somewhere along the line I became convinced that it was morally right to desegregate the schools.”

Plan Z, of course, was the “terminal” school desegregation plan, so named because McRae (who ate his own cooking by sending his children to Memphis public schools) didn’t want a succession of plans “A” through “Y.” But it was forever associated with one of its authors, MCS employee O.Z Stephens, who told me years later that “my identification with Plan Z killed me professionally in the school system.” His son David works for Shelby County Schools and has attended all of the meetings of the transition team and school board.

The senior Stephens thought busing was a disaster and has predicted that MCS charter surrender could also have dire consequences, but he is anything but a suburban firebrand or hater. He gave his working life to MCS and greatly respected both McRae and Willie Herenton, the superintendent during much of his tenure. McRae, he said, was “as easy on the school system and the city as he could possibly have been” and a less courageous judge could have passed the whole mess on to the appeals court.

For these and other reasons I am still somewhat hopeful about the schools merger. Pure conjecture on my part, but I suspect Mays is exercising as much judicial restraint as possible and well knows the limitations of a court-ordered “solution” to school desegregation and school system unification. He will let the political process play out as long as he can.

My attention span is not long, and I would rather walk on hot coals than sit through a five-hour meeting. But there is something positive and substantial in the Transition Planning Commission and, especially, the unified 23-member school board, even though it is not long for this world. Old white folks from the ‘burbs sit next to young black folks from Memphis, old black folks from the city sit next to young white folks from the suburbs; they look and listen, and speak their minds publicly. It’s hard to hate someone you’re sitting next to that long. John Aitken sits next to Kriner Cash and they occasionally share a private joke. Martavius Jones and David Pickler have probably spent more time together over the last two years than some spouses.

For this to transcend symbolism, both sides will have to compromise. The procedural shenanigans must end. We’re on the clock. MCS gave up its charter. Actions have consequences. I’m an Aitken fan, but that may be too much to ask, as even he knows, and he says he would willingly serve as an assistant superintendent. If Cash gets the job and really wants it, then I’m a Cash fan because I live in Memphis and want the city to prosper and personal differences don’t mean crap and I don’t believe in miracle-worker superintendents or 11th-hour national searches and Cash has the benefit of experience and knows the lay of the land.

Segregation is not the right word for what the muni’s are seeking. Legal segregation was the law in Robert McRae’s youth. Integration was the driving national force in Hardy Mays’ youth. Resegregation or de-facto segregation (and voluntary integration) is the driving force in Memphis (and many other big cities) in our time. But the suburban schools are not segregated in either a numerical way or a legal way, as the county commission’s filing this week states. There are certainly all-black schools. Southwind High School, which is almost all black, is the one I keep coming back to in my columns because it was such a calculated move when it was approved by the city and county school boards as a joint project. Federal Judge Bernice Donald almost forced the issue five years ago but she was overruled on appeal.

The next thunderbolt from federal court will have to account for the underlying factors that gave us a Southwind High School as well as, potentially, municipal schools. I think it has to come sooner rather than later. Ripe.

Vanities always reminds me of a high school yearbook signed by people we all swore we’d never forget, but did. Well, at least until Facebook brought them back into our lives and either confirmed that there was some real bond all along or that we hadn’t stayed in touch for a reason.

And when I think of yearbooks I think of the words, “Never Change” scrawled in big loopy letters. Seems like every other inscription in my senior yearbook said something like that: “Stay like you are and you’ll go far.” But was all of this a blessing or a curse? Even as a regular Clearasil user I never knew. And as time kept on slipping (x 3) into the future I knew less and less. Because most people didn’t seem to change much, really. They ripen and become more articulated. But changelessness seemed as inescapable as productions of Vanities in the 1970’s and ’80’s.

In the late 1970’s Vanities, an unassuming three act play about three cheerleaders (I’m hesitent to actually call them friends), growing up, going to college, and eventually moving away, was the most frequently produced play in America. The original New York production showcased the talents of an unknown girl from Memphis named Kathy Bates and ran for 4-years. In 1981 HBO filmed a version of the play with Annette O’Toole, Meredith Baxter Birney, and Shelly Hack. This televised version was my first brush with the play. And being in that hormonal stage where every relationship is absurdly intense, I watched it over and over again loving it more each time. I never wanted it to change, and it didn’t. And over time — and not all that much time, really — I got tired of it. Maybe I even started to despise it like Mary, the play’s worldly cheerleader turned erotic art peddler, grows to despise the provincial attitudes of her high school associates. It just seemed too damn easy to do. And something that accessible couldn’t possibly be worth doing, could it?

Vanities seemed like a strange choice for the New Moon theatre company, a growing indie that’s built a solid reputation by staging American classics and headier European works that have fallen between the cracks or out of the regional repertoire. Still, I was happy to revisit this once-popular show after all these years of writing it off as Lifetime bait waiting for its inevitable musical reincarnation. And even happier to discover that I may have underestimated this play about popularity and pointless living. It almost makes sense as a follow up to last season’s excellent Death of a Salesman.

Vanities may not be in the same league as Arthur Miller’s masterpiece, but there’s something undeniably real and powerfully archetypical about these three mean girls who go through changes, but never really change. And if New Moon’s production doesn’t quite give them the pep rally they deserve, it gives them life enough.

You know the old cliche about history repeating for those who don’t learn their history? The cheerleaders of Vanities hear about the assassination of JFK and immediately worry about how it might impact their plans for the big high school football game. Is it any wonder that they only experience the political and cultural upheaval of the 60’s and 70’s in purely aesthetic terms: Real hippies smell, but the hip, happening sounds of Broadway’s Hair is the winning ticket for sorority all-sing.

Liberated women aren’t defined by men, but the three vanities are of an older order. They are the college-educated harem girls for a new kind of American Sultan. So one’s burned a bra: Helluva striptease show.

The acting is low key, and a little cinematic. Every character could be more crisply rendered, every scene infused with more life. In act three especially, when nobody has anything left in common — Nothing they can talk about anyway — we need to see why these women need one another. The conflict is spelled out in the dialogue. The fun comes from watching them affirm one another while fighting, sometimes wickedly, for a better piece of the same neon tiara.

Emily Burnette takes on Joanne, the incurious breeder of the bunch who only wants to marry a rich man, make babies, and drink away the details. She does that exactly. And she says things like “I’d just die,” so often you start to wish she’d get on with it. Lauren Malone’s Kathy is an obsessive organizer, and a little on the mousey side. Heather Malone is too openly contemptuous of Joanne too soon, but when her Mary isn’t only glowering, she’s a lot of fun to watch.

I’ve always imagined there’s a lost fourth act to Vanities, where all the loose threads are neatly tied up. It seems like it should be the kind of play that ends with a big group hug. But instead there’s only innuendo and uncertainty, and the play is better for it. Will Mary find fullfillment selling erotic neon and sleeping with married men or will she settle down, find Christ and breed like Joanne? Will Kathy ever know what she wants to do with her life? Will the philandering husband Joanne can never leave turn out to be John Edwards? Will there ever be a time when the play’s comments about abortion don’t sound absolutely current?

The genius of Vanities is that it seems so insubstantial but it sticks with you. Like all that baggage spelled out in cryptic cliches in your senior yearbook.

Vanities, written by Jack Heifner. June 22 – July 1, 2012. Theatreworks. Fridays & Saturdays at 8 pm, Sundays at 2 pm. 15.00 Adults, $12.00 Seniors, Students & Military. 901-484-3467, www.newmoontheatre.org

Supremes Uphold Obamacare

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a somewhat surprising ruling, upheld the Affordable Healthcare Act Thursday.

In something of a surprise to most SCOTUS observers and pundits, the Supreme Court has upheld “Obamacare,” including its most controversial element, the individual insurance mandate.

There was some initial confusion, as CNN and Fox News originally reported that the mandate had been overturned. Here’s a pretty good summary of the decision from Huffington Post.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority decision, which carried by a 5-4 vote.

(My own somewhat specious theory for the surprising vote is that the rest of the SCOTUS judges are tired of Justice Scalia’s incessant political posturings under the guise of dissenting opinions and decided to piss him off, just for giggles.)

Also, the Washington Post has just put up an excellent interactive post that you can fill out to learn how the new healthcare law will affect you personally.

TTT Answer

The 2000 Memphis Tiger football team remarkably landed five players on Conference USA’s first-team All-Defense: Andre Arnold (DE), Idrees Bashir (DB), Marcus Bell (NT), Kamal Shakir (LB), and Michael Stone (DB).

Three of these players went on to NFL careers. Name the three . . . and the NFL teams with whom they played.

• BELL: Arizona Cardinals, Detroit Lions (2001-06)

• BASHIR: Indianapolis Colts, Carolina Panthers, Detroit Lions (2001-07)

• STONE: Arizona Cardinals, New England Patriots, Houston Texans (2001-06)

- JB

- Even under the tense circumstances of this week’s school board meeting, superintendents Aitken and Cash maintained cordial relations.

Reaction was rampant Wednesday to the continuing wrangles on the Unified School Board about the superintendency as well as to a new County Commission suit to block pending referenda on suburban school districts.

The Superintendency: Perhaps the most succinct summation of what happened at Tuesday night’s board meeting came from Tomeka Hart, an MCS holdover who put it this way Wednesday night: “It was about whether there would be a search or whether [John] Aitken would be superintendent. We voted for the search.”

Hart said the choice had been a fundamental one and took issue with published accounts suggesting the board, which debated for almost two hours the issue of whether to launch a search for a superintendent, had wasted its time.

She said that either Aitken, superintendent of Shelby County Schools, or Memphis City School superintendent Kriner Cash would be “fine with me,” but did not think the issue of who serves as superintendent should be closed yet.

Hart’s attitude contrasted with that of Martavius Jones, with whom she had led the move in December 2010 to surrender the MSC charter, thereby forcing the merger with SCS.

Jones had either abstained or voted No in the series of votes that led to a board vote authorizing chairman Billy Orgel to appoint a committee to arrange a search.

So did David Pickler, the former SCS chairman who is now running for a position on the permanent Unified Board as a supporter of municipal school independence.

In debate Tuesday night, both Jones and Pickler had based much of their positions on the premise that the board’s preeminent need was to digest the recommendations made to it earlier in the meeting by the Transition Planning Commission.

In separate conversations Wednesday, however, both admitted to nursing a belief that a failure to authorize or initiate a search would tend to confirm the prospects of one of the existing superintendents – Aitken, in the case of Pickler, who is a resolute supporter of the Shelby County Schools chief; Cash, in the case of Jones, who maintains an optimism about the MCS head’s prospects.

Pickler’s belief is founded on the fact that Aitken is already the superintendent of the only duly constituted county educational unit, that he has a contract that extends all the way to 2005, and that, failing any action by the school board to designate a different superintendent, he is the de facto chief of whatever expanded version of a county school system is produced by the MCS-SCS merger.

For his part, Jones is undeterred by the action of the board last week in declining to renew Cash’s contract, which is due to expire in August 2013, the point at which the MCS-SCS merger becomes effective. (On the same night, the board rejected a motion of non-renewal for Aitken.)

As Jones points out, the current 23-member School Board is an interim body. On August 2, a new 7-member permanent board will be elected.

A necessary parenthesis, because this gets hard to follow: The seven winners of the August races will take office immediately, co-existing for a year with holdovers from the interim board, the two groups together sustaiing a 23-member body until August 2013.

Since several of the contested races pit current members against each other, temporary vacancies will be created, which the County Commission will fill for the meantime. But as of August 2013 only the elected seven will constitute the permanent board. Complicated, right? You betcha!

Anaother complication is that some point the County Commission will petition Judge Mays to expand the board to 13, at which point the sequence of appointed members and subsequent elections will commence again. Whew! End of necessary parenthesis.

Clearly, the composition of the Unified Board is due for so many potential changeovers as to make it possible, Jones contends, for the existence at some point of a board membership friendly to Cash, one that could decide to hire the MCS leader, despite his apparent rejection last week.

Jones’ emergence as a full-tilt booster of Cash has surprised many observers, who had gotten used to his role as an apostle of county-wide school unification for the last year and a half. Jones concedes that there has been a boom for Aitken on the part of other such unifiers, but he professes doubts that he SCS superintendent has enough experience with the inner city, and he points out that a 150,000 –student county-wide school system will still be predominantly urban.

There was an ironic footnote to Jones’ position on Wednesday afternoon. As he was discussing the schools situation on a downtown street corner with this reporter, a retired Marine colonel named David Dotson happened by.

Recognizing Jones, Dotson initiated a conversation in which he courteously but bluntly (“You’re fartin’ in the wind,” he said at one point) told Jones that resistance to efforts by Shelby County’s six suburban municipalities to establish independent school systems was futile, akin to a husband’s trying to tell an estranged wife she had no power to leave.

And Cash, whose champion Jones had become, was not only not a unifying element, he was one of the major causes of the breakup, insisted Dotson, who went on to praise Aitken, likening the SCS head’s persona to that of Marine officers he had served with.

The Commission Lawsuit: Meanwhile, it became apparent that there was resistance from within Shelby County government and from within the Shelby County Commission itself to the suit filed under the auspices of the Commission requesting intercession by presiding U,S. District Judge Hardy Mays against the carrying out of the schooled August 2 referenda.

In separate news releases District 4 (suburban) commissioners Terry Roland and Chris Thomas challenged the legality of the suit as having been decided upon in violation of the state Sunshine Law and without an expressly conducted and legally binding vote by the Commission.

District4ReleaseonLawSuitConcerningSchools.pdfPressReleaseComm.Roland6-27-12.pdf

And Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell, who increasingly has become a front-and-center presence in the ongoing schools matters, issued his own objection to the suit.

In a press release Wednesday, Luttrell said: “I’m not surprised by the lawsuit. However, I was shocked by the language. The lawsuit needs to be based on constitutional merits and not on race. Additionally, state law allows for these special elections. They should be held as planned.”

He continued: “Citizens in municipalities within Shelby County should have the right to vote on whether they want to operate their own school systems,” And the press release containing Luttrell’s comments pointedly noted that “the Shelby County Attorney’s Office has received a request to investigate whether the lawsuit was legally filed since no official vote was taken by the entire Shelby County Commission” and that “Shelby County Attorney Kelly Rayne will also determine whether any sunshine laws were violated.” rellOpposesLawsuittoBlockMunicipalSchoolElections6-27-12.pdf

- JB

- “Fartin’ in the wind…”” Martavius Jones and Colonel Dotson in their street-corner dialogue

Flaming Lips’ Wayne Coyne Talks Tour

Chris Davis chatted with Flaming Lips lead man Wayne Coyne, who was in Memphis to kick off a 24-hour tour.

Man of the Moment

By the time the current week is out, the 23-member Unified School Board of Shelby County will have publicly wrestled once more with the vexing question of who is to lead the educational system which, somewhat more than a year from now, will formally succeed and replace the two side-by-side systems of Memphis City Schools and Shelby County Schools.

In a marathon session last week, the board eliminated one potential candidate, voting not to renew the contract of MCS superintendent Kriner Cash by a majority decision, and, by an identical vote, 14-8 (with one absentee) keeping alive the status of SCS superintendent John Aitken. Cash’s contract expires in August 2013, the same month that MCS and SCS were originally set to merge. (Sort of, as it turned out.)

Aitken’s contract had been extended to 2015 by the erstwhile SCS board, and the Unified Board’s decision last week against non-renewal of that contract kept alive the prospects of the SCS superintendent to manage the combined system — especially as that system will technically be a continuation of Shelby County Schools.

The word “unified” in the provisional name of the provisional governing board is ironic in the extreme. First of all, the board is one of those proverbial camels put together by a committee — assisted in this case, by a judge, U.S. District Judge Samuel Mays. It was Mays whose adept handling of several overlapping litigations last summer induced numerous warring jurisdictions — educational and civil, urban, suburban, and state — to agree on a compromise regarding city and county school merger that became the basis for a consent decree.

Strictly speaking, the board is composed of the nine members of the former Memphis City Schools Board, the seven members of the former Shelby County Schools (suburban) board, and seven members appointed late last year by the Shelby County Commission to represent the seven county-wide districts recognized in Mays’ consent decree.

In a little over a month, on August 2nd, the county’s voters will select permanent members for those seven districts, which the County Commission intends to enlarge to 13 eventually, if Mays should agree. Those newly elected members won’t take office until the merger date of August 2013, however, although they might be permitted to take office earlier — again, under dispensation from Judge Mays.

But all of that is another story. Right now, it is the highly fractious “unified” board which governs and, after six or seven months of desultory existence, has finally got down to the nut-cutting stage.

Whatever Kriner Cash’s critics might think of him or of his often flamboyant and arguably over-bureaucratic four-year reign, the MCS superintendent comported himself with dignity last week, as 22 members of the Unified Board (absent only the ever-volatile Rev. Kenneth Whalum of the MCS contingent) wrangled for hours over his status.

For the most part, Cash — who sat between Aitken and MCS holdover Martavius Jones, a onetime critic become Cash defender — betrayed no emotion and remained Buddha-like as discussion went this way and that — sometimes indirectly, sometimes all too bluntly — regarding his status. And none of this was happening in a vacuum.

Outside the Teaching and Learning Academy building on Union Avenue, where the board was gearing up for the first “showdown meeting” on the superintendency last week, others had taken sides. Chanting and carrying placards on the front grounds of the building, a large group was supportive of Aitken’s candidacy.

The Aitken boosters were opposed by a smaller group, led by the Rev. Isaac Richmond, who was attempting to prevent the board from hiring the current Shelby County Schools superintendent (whom they identified on pass-out materials last week as “Robert Aitken,” a gaffe that prompted John Aitken to jest that his “cousin” Robert was indeed, as the handouts proclaimed, “unfit” to head the school board.

In preliminary proceedings as the meeting got underway, Aitken (whose contract, along with that of Cash, was destined for review) demonstrated perhaps an unintentional sense of irony by announcing a weather-oriented awareness program for students entitled “After the Storm.”

That was, of course, before the storm, which began to roil after the announcement period, with a proposal from member Jeff Warren to postpone voting until the current week, when the subject would be whether to conduct a candidate search or adopt some other method.

Then the clouds began to rumble good and proper, with a variety of possibilities being proposed. It brought to mind remarks made earlier in the day to the Memphis Rotary Club by Shelby County mayor Mark Luttrell.

Asked after a luncheon address if John Aitken was the logical choice, Luttrell acknowledged the SCS superintendent might have a slight advantage but said that both current superintendents were still eligible. Two other possibilities he suggested: hiring from within and hiring someone with executive ability from the larger community.

Clearly, Luttrell was not in favor of a prolonged search, nor one beyond the county’s borders. But others were. Sara Lewis, ex of the MCS board, had a colorful metaphor in favor of a search process. “Unless I go outside in the parking lot, I don’t know what’s out there.”

David Pickler, the former longtime SCS chairman, warned of letting too much time pass and touted the action of the legislatively created Transition Planning Commission, to which he also belongs, in suggesting August as a terminal point of decision on the superintendency. (That had been more or less what an adopted motion by Luttrell, also a TPC member, had suggested.)

“I believe this is the defining moment on this board. The issue is, who is going to lead?” Pickler said.

Ultimately, the board voted to defer action on hiring a superintendent or on a search process to that end until this week. And then, already several hours into the meeting, came a motion from SCS member Mike Wissman, who doubles as mayor of suburban Arlington, one of six municipalities actively contemplating a breakaway from the Unified System.

Wissman called for “the hard vote” on Cash’s status. Delayed by almost another hour of wrangling, it came, with the aforementioned 14-8 verdict against Cash, followed by the same totals to keep Aitken’s status active. In general, although there were exceptions both ways, former MCS board members voted with Cash and former SCS members voted against him. What made the difference was that the seven commission appointees on the board voted 6-1 against Cash.

It remained uncertain how many of those who provided last week’s prevailing 14-vote majority Aitken can count on in his hopes to be confirmed as permanent superintendent of the soon-to-be unified Shelby County Schools. (His official position is that, as his deputy Tim Setterlund has put it, “He’s already got the job,” but Aitken and everybody else know that premise, based on Aitken’s extended contract, will require adjudication.)

The Aitken boom began several weeks ago as several key individuals across the spectrum of interested parties — various columnists, a sizeable contingent of the TPC, and likely Luttrell among them — began to view the SCS superintendent as someone who could (if anybody could) reconcile the wary residents of suburbia to the idea of a merged all-county educational system.

It is by now taken for granted by almost everyone that the August 2nd referenda in favor of establishing separate municipal systems will be overwhelmingly approved in the six cities in which they will be held — Germantown, Collierville, Bartlett, Arlington, Lakeland, and Millington. Proponents of that outcome, like Pickler, a candidate for the Unified Board, have made it clear that they, too, see Aitken as the ideal superintendent of the new unified district, someone suburbanites would feel comfortable with in negotiating for shared services for their districts.

Those two sources of support for Aitken, from opposite ends of the stick, would ordinarily have seemed to ensure his selection. But it was never going to be easy, as some racially charged opposition from within the inner city, typified in that Isaac Richmond circular, made clear.

And there’s another, larger context. The selection of a school superintendent for Memphis’ future unified district is bound to get some national attention.

For one thing, what Memphis City Schools and Shelby County Schools are undertaking is the biggest school system merger in American history. There are much bigger school systems, but this is the biggest merger because both systems — Memphis with roughly 103,000 students and Shelby County with approximately 46,000 students — are sizable. That fact alone has drawn the attention of The New York Times and other national news organizations.

Second, as indicated, the story comes with both a racial angle and a city-and-suburban angle. Those themes are catnip to national news editors who from time to time see Memphis and Shelby County as a microcosm of social change in America.

And third, the selection of a superintendent will put a single face on a complicated story that until now has had many faces — among them superintendents Cash and Aitken and school board members Pickler, Jones, and Tomeka Hart (Jones’ partner in furthering the late 2010 MCS charter surrender that forced city/county school merger, and now, largely on the strength of that, a congressional candidate).

Involved in the saga, too, are the concepts of consolidation, municipal school systems, and special school districts, all of which have both statewide and national relevance.

The person chosen as superintendent will immediately become instrumental, too, in the transition (or “migration,” as the Transition Planning Commission calls it) to a new era of innovative educational change.

When the TPC was created as an adjunct of the Norris-Todd Act of 2011, it was widely regarded (like the act itself, which lifted a state ban on new special or municipal districts as of August 2013, the merger date) as part of a suburban defense against consolidation.

But the 21-member TPC, though appointed with preponderantly suburban input, proved to be a harmonious, utterly sincere and hard-working group which emerged with a plan, called Multiple Paths to Achievement, that is based on the assumption of a countywide system of 150,000 students but allows for maximum diversity.

That diversity involves not only the pre-existing MCS and SCS systems but creations of a reform-minded state Department of Education under Governor Bill Haslam. These include a whole panoply of new charter schools; an Achievement School District, which will take over administration of failing schools, many of them in Memphis; and an Innovative School District, designed to upgrade the status of better-performing schools.

And more is yet to come, including the resolution of how new municipal districts might interface with the unified district.

Not since the twilight of Willie Herenton’s career as Memphis superintendent in the late 1980s has such attention been focused on the school system and the question of leadership. Herenton, by the way, said last week he would make his preference known for the current job at a later time.

For the time being, it was still the 23-member provisional unified board which had the decision to make on a choice for superintendent.

If Aitken should become that person, expect to see and hear a lot of him for the next three years.

A Visit With John Aitken

John Aitken, all 6′ 9″ of him, ducks under a doorway, takes a chair next to a wooden Indian, and welcomes the visitors into his office. It’s been a hectic week, but the SCS superintendent is relaxed and joking about his office memorabilia.

“That’s Big Chief,” he says, hooking a finger at one of the two cigar-store Indians that occupy corners of his office. “There’s no special significance. I think one kid once called me chief.”

There are pictures of Aitken in Elvis costumes that he wore when he performed at the employee appreciation picnics.

The West Helena, Arkansas, native (who went to high school with Arkansas’ former U.S. senator Blanche Lambert Lincoln), is a serious Elvis fan and a more-than-passable singer who plays guitar and also does Frank Sinatra, Garth Brooks, and church music. (On a visit home after he had begun his educational career, he was coaxed into singing in a local production of Li’l Abner.)

In March he sang “Sunrise Sunset” at his daughter’s wedding, somehow getting through the tear-jerking lyrics (“Is this the little girl I carried … When did she get to be a beauty?”) before giving her away at the altar.

“That was tough,” he says.

Aitken’s current predicament is tough in another way — having to do with the uncertainty of things. The events of the meeting earlier in the week would seem to give Aitken a leg up, unless the board opts to do a search for another candidate.

Aitken says he and Cash are friends and talk on the phone nearly every day and meet face-to-face a couple times a week. Aitken says if he does not get the top job, he would be willing to work as an assistant.

Though he is every inch the education professional, Aitken exudes the common touch. He and his wife, a nurse in a neo-natal intensive care unit, have two sons and a daughter ranging in age from 23 to 32 years old. The younger son, a special-needs student, is adopted.

Aitken’s father worked at a lumber mill in West Helena and his mother was choir director at the local Baptist church. He got a basketball scholarship to Henderson State College in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. After graduation, he taught and coached for three years in Arkansas and for nine years at Collierville High School (“primarily basketball, but you end up coaching everything”), then moved to Houston High School in Germantown where he was principal. He was named superintendent of Shelby County Schools in 2009, a year after counterpart Cash came to MCS.

He is sympathetic regarding Cash’s ordeal at that week’s board meeting. “I hoped that everybody kept that in mind, the human element. I admired him for sitting there. It’s hard, it’s tough on me.”

Whoever gets to be superintendent of the unified system will have it tough, too, he knows. “I don’t know if there’s a superman out there who’s got everything that job requires. You’d have to bring in some folks around you with a variety of skills.”

Aitken is prepared to do just that, but he also believes that he owns “some qualities that can inspire and heal and encourage.”

He says he knows the larger community, including the inner city and would welcome the opportunity to head the new district, even if it ends up being shorn of the suburban areas that formerly made up SCS. “I adopted a disadvantaged kid, whose parents had been evicted from a housing project in Memphis. My wife works as an intensive-care nurse at the Med. We understand that community.”

Aitken says he understands the need for a search process, even an extended one, if need be. “I’m not opposed to that. If I’m not chosen, I’ve got to look at every opportunity. I’m willing to be an assistant.”

But the ex-athlete and coach concedes, “There’s a little competitive streak in you. You want to make things right. And you want to win.”

Aitken has followed the deliberations of the TPC and the turns of state educational policy with great care. He knows that the “Multiple Achievement Paths” model will involve great complexity and that the process of educational innovation will continue. He hopes that the new district in Shelby County becomes a model for the rest of the nation.

But his ultimate premise is this: “There’s much that comes and goes, but what’s constant is that one teacher in front of that kid in every classroom.”

I admit, controversy is my stock-in-trade. It’s what comes of being a contrarian. So it shouldn’t surprise anyone if I admit to yet one more unpopular opinion: I am a union man.

I believe working men and women need something, now more than ever, to level the playing field with corporations that have accreted so much untrammeled power over our lives. I don’t buy the benevolent paternalism malarkey many union-hostile companies use, namely that they treat their employees so well they don’t need a union.

If that sounds like what plantation owners used to say about their slaves, there’s a reason. Many of these same companies don’t pay their employees a living wage or provide what used to be called fringe benefits. Besides, who needs benevolence when you can have bargaining power?

I grew up in Pittsburgh, a union town if there ever was one. The AFL-CIO got its start there. It was also the site of one of the most infamous labor union uprisings in American history, the Homestead Steel strike. I knew who Walter Reuther and George Meany were almost before I knew who Roberto Clemente was.

So it was only natural that I would join a union when I started working as a part-time cabbie. And it wasn’t just any old union; it was the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. You know, Jimmy Hoffa’s gang (but don’t ask me where he’s buried). After my cabbie gig ended (becoming a lawyer seemed like a better career path), I proudly carried my “honorable withdrawal card,” which entitled me to rejoin the union at any time, until it eventually turned to dust.

What didn’t turn to dust was my belief in unions, which carried me through the difficult days during which I represented the air traffic controllers in Memphis who Ronald Reagan unceremoniously fired, even as that president was condemning the Polish government’s attempt to outlaw its national union. It continues right up to the present, when I have seen unions withstand the withering pressure of what my generation used to call the “establishment” to deprive them of their most basic right: collective bargaining.

What amazes me is that being a supporter of unions can be unpopular. And yet, that’s what it’s become with unions being blamed for, among other things, the stupidity of corporate decision-makers, as they have been recently for the travails of the auto industry, despite the credit those unions are due for the decades of that industry’s success.

While corporations have their own advocacy organization (the U.S. Chamber of Commerce), and even — based on its recent history — their own court (aka the “Supremes”), and while grossly overpaid executives have their own protection (quiescent shareholders and complicit boards of directors), workers are being increasingly left to their own devices as their unions get vilified and crushed left and right.

As we’ve seen recently with what happened in Wisconsin and elsewhere, it’s open season on unions. Not even the unions’ traditional allies, like the Democratic Party, are coming to their defense, as evidenced by President Obama’s notable absence from the Wisconsin recall campaign.

It is no accident that income disparity in this country — the most disproportionate in generations — coincides with the demise of labor unions or that so many people have fallen out of what used to be called the middle class as unions have become increasingly marginalized.

Companies are paying their executives outlandishly at the expense of their workers while at the same time downsizing and outsourcing tens of thousands of jobs — a business model one of the candidates for the presidency embraced when he led a so-called vulture capital company and presumably would still favor if elected.

Memphis has a long and storied history of unionism, not the least significant example of which is the sanitation workers union that was so instrumental in the fight for civil rights. Labor unions in Memphis have been at the forefront of protecting, in particular, the rights of African-American workers, whether it’s been teachers, hospital workers, postal workers, or other municipal workers.

I have always suspected that much of the antagonism in this town towards unions is attributable to that fact that African-Americans here are (and historically have been) the primary beneficiaries of union membership.

What a shame.

Memphis attorney Marty Aussenberg is an occasional essayist for the Flyer‘s online edition — as “Gadfly” — and a frequent commenter at memphisflyer.com.