Friday nights are a movie theater’s bread and butter, but on Friday, January 9, 2015, the Malco Ridgeway Cinema Grill theater was closed to the public. The lobby was still bustling, but on this night it was with a crowd of dressed-up VIPs sipping champagne, munching on movie-themed hors d’oeuvres, and talking about the old days. Malco Theatres has been welcoming Friday-night moviegoers for 100 years, and it was time for celebration.

Naturally, Malco treated its extended family to a movie. There were four to choose from, tracing the century-long evolution of films that had brightened Malco’s screens and drawn patrons through the doors of dozens of theaters: from Hollywood’s miracle year, 1939, The Wizard of Oz; from the post-studio system 1960s, The Sound of Music; from the auteurist 1970s, The Godfather; and from the dawn of computer-generated imagery, 1994’s Forrest Gump. (For the record, The Godfather was the most popular choice among the partygoers.)

“We as a species are biologically driven to go to the movies,” says Jeff Kaufman, Malco’s senior vice president of film and marketing. “We spent 25,000 years living in caves, being told stories by firelight. That’s how our species evolved. You can see cave drawings all over the world that are thousands of years old. That communal experience that our forefathers had translates into what we do today in the movie theater.”

Experiments with moving pictures date back to the mid-19th century, soon after the invention of photography. In the 1880s, watching a movie was a personal affair. You put a coin in a Kinetoscope machine and peered into the eyepiece to see short films of vaudeville acts or scantily clad women dancing. The first public exhibition of a projected film in America was in New York City in 1898. The 1903 film The Great Train Robbery caused a sensation with a startling innovation: a plot. “The first theater in Memphis was opened in 1905 by Charles Dinstuhl, next to his candy store on the corner of Washington and Main. It was called the Theatorium Theatre,” says Vincent Astor, historian and author of the 2013 book Memphis Movie Theatres. “It was an actual nickelodeon with a large number of seats in front of a screen. It was a storefront, but it was the first storefront converted to show movies.”

Soon, theaters like the Optic and the Majestic dotted downtown. “Memphis has always been a big theater town,” says Astor. “There were a handful of [vaudeville] theaters in the 19th century. Several of them ended up being used for films when it was profitable to do that.”

Short subjects still ruled during the first decade of the 20th century, but films gradually became longer. The first to reach what we now consider feature length was the 1906 Australian crime epic The Story of the Kelly Gang. European cinema led the way until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, which coincided with a flowering of film production in a formerly sleepy California town called Hollywood.

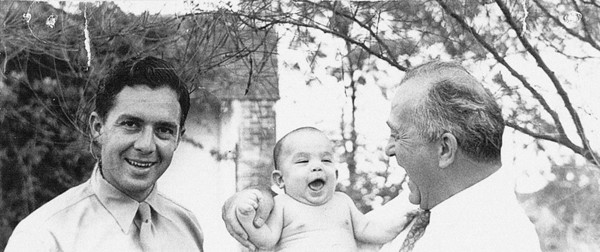

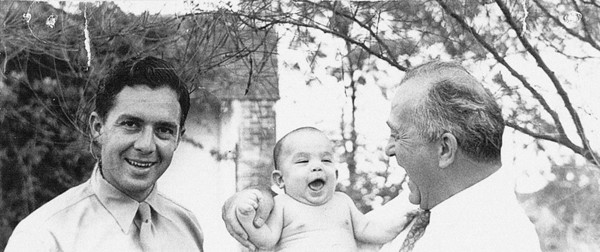

M.A. Lightman Sr. holding Stephen Lightman with M.A. Jr.

In 1915, Nashville native and Vanderbilt University graduate M.A. Lightman rented a storefront in Sheffield, Alabama, and opened a movie theater called the Liberty Theater. By then, the modern movie theater business was taking shape. First, theater owners from the informal vaudeville circuits banded together into multi-state chains, then the movie studios themselves, like Warner Brothers and Paramount, got into the business in what’s called today a move toward vertical integration. But there was no shortage of independently owned movie theaters in America. “The theaters came and went. There were different circuits that owned different theaters, and they changed names a lot,” says Astor.

Entrepreneurs like Lightman leveraged their successes into opening more theaters. By 1919, his Sterling Amusement Company owned three theaters in Alabama. He soon sold those theaters and entered the Little Rock market. M.A. Lightman’s father, Joseph, was in construction, and in 1925, the two got together to build the Hillsboro Theatre in their native Nashville. That theater is still around today as the Bellcourt Theatre, an independent art house cinema. The family arrangement was not unusual. “There were a bunch of families, many of them Italian, who owned theaters everywhere,” says Astor.

Malco (M.A. Lightman Company) got its name in 1926. The Lightman family business spread across Arkansas, and then, in 1929, they crossed the river. “The Linden Circle was their first theater in Memphis,” says Astor.

At the same time, movies were undergoing the first of what would be many technological upheavals: the introduction of sound. “The Jazz Singer actually played at Ellis Auditorium,” says Astor. “One of the reasons for that was, at the end of the 1920s, when sound came in, it was just as profound a change as has been the change from film to digital. You had to do it. There were theaters like the Majestic where the owners closed the theater rather than spend the money to convert to sound. Several of the really early sound pictures were at the auditorium, because it was easier to truck in the equipment and put it on the big stage and show the film and then truck it out again, because it was designed for that, and the size didn’t matter. It was cheaper to do that instead of converting another theater.”

During the Depression, the movie theater business was one of the few industries that thrived. Tickets were cheap, and people needed escapist entertainment. In 1935, Malco opened the Memphian Theater on Cooper. It would become a Midtown neighborhood icon and a favorite of Elvis Presley, who famously rented the entire theater for late-night screenings with his friends in the ’60s. Later, it became the first Playhouse on the Square; today, it’s Circuit Playhouse, which still hosts films for the Indie Memphis film festival.

This was the age of the movie palaces, with ornate, 1,000-seat theaters like Lowe’s Palace, the Strand, and the Princess packing in people for first-run Hollywood fare. In 1940, Malco bought a former vaudeville theater at the corner of Main and Beale Street called the Orpheum and transformed it into the growing chain’s flagship property. Malco would have its corporate offices there for many years.

The Arrival of Television

But change was again brewing in the theater industry. The major Hollywood studios had been under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for years regarding their vertically integrated system of movie distribution. The market power that came from owning a huge number of the theaters that showed their films often forced the hands of independent owners like Malco. In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled in United States vs. Paramount Pictures that studio ownership of theaters constituted an unlawful monopoly. The ruling weakened the power of the Hollywood studios and consequently led to fewer movies being produced.

In 1951, Malco opened the Crosstown, a state-of-the-art, 1,400-seat theater next to the Sears Building. The neon sign atop its marquee was 90-feet tall and employed more than a mile of neon tubing. It was the crown jewel of the 63-theater Malco empire that stretched from Kentucky to New Orleans. But it would be the last of the movie palaces built in Memphis. Hollywood, still reeling from the antitrust ruling, faced a challenger for the eyes and minds of America: television.

“Television scared them to death,” Stephen Lightman, grandson of M.A. Lightman and current president of Malco told what is now Inside Memphis Business (formerly Memphis Business Quarterly) last December. “They thought it was the end — people weren’t going to go out of the house; they were going to sit at home and be entertained.”

Hollywood responded by trying to create a film experience in the theater that was not possible in the living room. TVs were square, so widescreen became the standard for film. Stereophonic sound completely blew away the tinny din of the TV speaker, and early experiments in stereo vision led to the short-lived 3D fad, which produced a few classics like The Creature from the Black Lagoon. “The movie business has always been in flux,” says Astor. “Since the end of the second World War, they have always had to try and one-up something technological.”

The movies continued to be popular, but the margins in the theater business were shrinking. With their high overhead costs, the movie palaces went into slow decline. The late 1950s were the golden age of the drive-in, an innovation that had begun in the late 1930s but exploded in popularity with the newly mobile teenagers of the baby boom. With the drive-ins came a new wave of movies designed for cheap thrills that featured rock-and-roll, motorcycles, shabby monsters, and scantily clad babes. “That’s why movies became more exploitive — they had to figure out a way to get people out of the house,” says director Mike McCarthy, whose Time Warp Drive-In series has become a popular staple at Malco’s Summer Drive-In. “If there wasn’t enough sex and violence in the house, there was some at the drive-in.”

David Tashie, Stephen Lightman, Jimmy Tashie, Bob Levy

Integration and the Birth of the “Multiplex”

M.A. Lightman passed away in 1958, leaving the business to his two sons, M.A. Lightman Jr. and Richard Lightman. With the civil rights movement spreading across the South, the brothers would oversee the racial integration of their theaters. African-America patrons had historically been confined to separate balconies, but one day in 1962, without fanfare, and after consulting with the Memphis Bi-Racial Committee, the Malco on Beale sold orchestra-level seats to a single African-American couple. The next week, two couples were admitted, and within a month, the colored balcony had become a thing of the past.

Since before the antitrust ruling, films would be released first in prestigious movie palaces, where they’d play until returns started to diminish, then be shunted off to smaller, neighborhood theaters. But as the 1960s waned, the squeeze was on. “Theater attendance had been going down for years, and the neighborhood theaters were among the first to go,” says Astor. “They had become esoteric. They were not playing to a general audience. They were playing to a neighborhood, which was mostly staying home and watching television.”

The AMC theater chain pioneered the “multiplex” concept, opening a four-screen theater in Kansas City in 1966. Staggering movie start times across the screens allowed the same-sized crew to sell tickets and serve refreshments to four times as many patrons. The Highland Quartet, which opened in 1971, was the first Malco multiplex. It was the final nail in the coffin of the movie palaces. “It got to the point where the smaller theaters just weren’t making money,” says Astor. “In order to fill the big theaters, the Malco and Lowe’s Palace became black exploitation and kung fu theaters.”

The 1962 marquee for the Summer Twin Drive-In in Memphis

The early 1970s also saw the evolution of the contemporary blockbuster mentality. Studios were cutting more prints of their biggest movies and sending them out everywhere at once. With multiplex screens proliferating around the country, that meant that everyone who wanted to see a movie could see it pretty much immediately. Instead of being spread out over the course of months, the financial returns for films was more front-loaded, and opening weekend became more important.

In June 1977, one month after Star Wars hit theaters, the Malco Ridgeway Quartet opened in East Memphis. Downtown was hollowing out, and Malco sold its namesake theater and moved its offices to the multiplex. Astor, who had gotten a job at the Malco after falling in love with its crumbling granduer during a screening of True Grit, recalls, “When it was sold to the Memphis Development Foundation, I was retained, the only Malco employee to stay, because I knew where the fuses and the skeletons were. I had done a lot of research on the history of the theater, so they kept me.” The newly rechristened Orpheum returned to its live theater roots and remains a downtown landmark.

“Selling the Experience”

Over the years, Malco Theatres has survived multiple takeover attempts, but today, 100 years after M.A. Lightman’s Liberty Theater, it remains family owned, and is thriving. Every night, Malco opens the doors to 349 screens in 33 locations. “We’re sure happy we didn’t sell, because any investment we had made with the money would probably not have done as well as the movie business,” Stephen Lightman told Inside Memphis Business.

The movie business today is, as always, in a state of flux. “There aren’t too many businesses that have the responsibility to recapitalize themselves twice over the course of a business lifetime,” says Kaufman, Malco’s film and marketing SVP. “Theatrical exhibition went from slanted floors to stadium seating, so we had to recapitalize the insides of the auditoriums. Then it went from 35mm to digital, so we had to recapitalize the [projection] booth. It was a lot of money and a lot of effort.”

“Malco, as far as digital was concerned, went for it whole hog,” says Astor. “The most complicated digital installation you can do is at a drive-in, and Malco did it on four screens.”

But there’s another side to the digital revolution: High definition big screens and surround sound are not just found in theaters any more but in living rooms. And beginning with VCRs in the 1980s, DVDs in the 1990s, Blu-Ray in the 2000s, and now Netflix and digital streaming in the 2010s, audiences have access to an unprecedented variety of motion-picture content. These trends have some pundits preparing obituaries for the theater industry.

But Malco has heard that rhetoric before. Despite the doomsayers, total domestic box office in 2014 topped

$10 billion. Industry-wide, the number of theatrical tickets sold has remained pretty constant over the past 25 years. The average American sees four movies in the theater per year. “The MPAA [Motion Picture Association of America] says that about 10 percent of the people buy about half of the tickets,” says Kaufman.

To keep those folks coming back and attract new patrons, the industry has deployed all of the tricks it has learned over its history. 3D technology made a quantum leap forward. New audio technologies, such as Dolby’s Atmos system, offer unprecedented sound quality. And the design of Malco’s multiplexes now echoes the movie palaces of old.

The Malco Paradiso theater in East Memphis

“Marcus Lowe, in the beginnings of his great success, said ‘We sell tickets to theaters, not movies.’ That’s really the case with Malco,” says Astor. “They’re selling the experience. All of their theaters might not be as beautiful as the Paradiso, but it’s still the whole experience. It’s the movies, the special effects, the food, everything. And the presentation has always been their strongest point.”

Kaufman says it’s Malco’s commitment to quality that has sustained them: “It’s not brain surgery, but it is attention to detail on a lot of different levels. Theaters these days are more akin to the kinds of theaters we grew up going to. They’re visually arresting, they’ve fun to go to. It’s not just a box with four screens like you saw in the 1960s and 1970s.”

Inside those theaters, the fare has become more varied. Digital projection has enabled live, high-definition streaming of events. Malco offers its theaters for use by film festivals such as Indie Memphis and has helped give Memphis’ independent film scene a home. And as an increasingly educated filmgoing public wants to experience the classics with a big audience, Malco has partnered with McCarthy and Black Lodge Video for the popular Time Warp Drive-In series.

Larry Etter, Malco’s senior vice president of food services, says, “I’ve lived in Memphis since 1970, and I think Memphians are spoiled. Until you get outside of Memphis and watch movies in other facilities, you don’t realize the quality of the product that the Malco family, the Lightmans, the Tashies, the Levys have put together for their communities. They really think the quality of presentation is paramount. If you’re paying for it, you deserve the very best.”

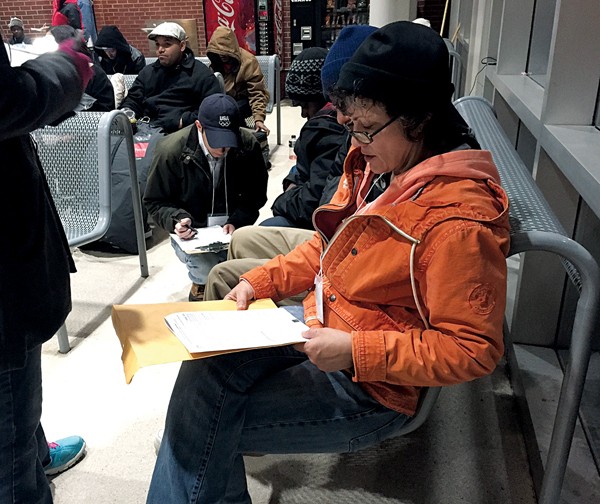

Photo by Fontaine Pearson

Photo by Fontaine Pearson

John Klyce Minervini

John Klyce Minervini  John Klyce Minervini

John Klyce Minervini  John Klyce Minervini

John Klyce Minervini  John Klyce Minervini

John Klyce Minervini

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski  Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips