Dang

Why does there need to be a documentary about the Memphis Country Blues Society, and the Country Blues Festivals of 1967, ‘68, and ‘69? So director Augusta Palmer can get local treasure Jimmy Crosthwait to tell stories like this one about scolding the Rolling Stones, convincing them to play in Memphis for free, and how the whole thing gets screwed up in the end. That’s why.

Jimmy Crosthwait:

See, the Rolling Stones had recorded Reverend Robert Wilkins song, “Prodigal Son” without giving him credit as a writer. Well, at some point, while organizing the ‘69 festival, [Insect Trust Guitarist] Bill Barth and Chris Wimmer went over to Reverend Wilkins’ house and was able to get in touch with the Rolling Stones from Wilkins’ phone. I think they probably called Stanley Booth who was writing his story on the stones, “Dance with the Devil.” And that’s how they got the number. So, in the end they’re talking to Mick Jagger who’s apologizing, and wanting to make it all right with the reverend Robert Wilkins. Well, Barth asks, “How would you like to play the ‘69 Memphis Country Blues Festival?” And they said, “Fine.” If the city can come up with some plane tickets, and put them up, they’d be more than happy to do that gratis. So then they asked the Reverend Robert Wilkins if he would like to talk to Mick Jagger. And Robert, he says, “No, you tell that boy I’ll talk to him in person.”

Money for plane tickets and lodging never materialized so the concert never happened. But even if it had, a Stones appearance would have just been icing on a big, bluesy cake.

The first Memphis Country Blues festival was assembled with almost no money. According to legend it was kickstarted with $50 from Jim Dickinson’s paycheck and a chunk of hashish that ranges from baseball to softball size depending on who’s telling the story.

“I think all the old blues players were paid money, but everybody got paid in red Lebanese hash,” Crosthwait confirms. Barth, he says, wanted to make sure everybody was happy with their compensation.

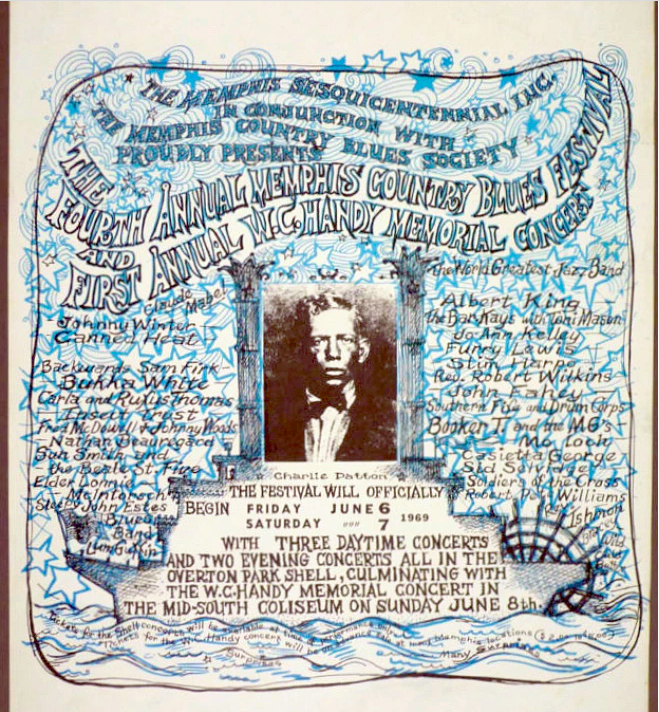

The festival showcased artists like Slim Harpo, Bukka White, Fred McDowell, Moloch, Johnny Winter, Joe Callicott, Furry Lewis, Albert King and Canned Heat. It attracted huge crowds and was the subject of a 2-hour PBS special hosted by Steve Allen in ‘69.

“Somebody told me [Last Train to Memphis/Sweet Soul Music author] Peter Guralnick and his brother drove in from Philadelphia in a VW bus. That the ‘69 festival really ignited the spark of his love for Memphis music. Robert Gordon shared the clip of Guralnick in my trailer. I didn’t shoot that, but hope to interview him.

“I feel like all these people involved in the festival were really seekers,” Palmer says. “Some of that was just following along with the party, of course. It was a very psychedelic time and the tendency is to think that’s all just about having a great time and getting really messed up. But I think there was also the sense that they were really seeing the world in a new way and trying to remake the world.”

Palmer tells the story of young white musicians going to older black artists for mentorship. Crosthwait illustrates the point by recalling the 1968 festival, which was held in what is now the Levitt Shell on July 20, 3-months after Martin Luther King was assassinated at the nearby Lorraine Motel.

Kickstarting a Documentary About the Memphis Country Blues Society

“We had a complete roster of black and white musicians, and a complete audience of black-and-white people there at the show,” Crosthwait says. Nationally there was division and unrest, but not at the Memphis Country Blues Festival. “I didn’t really think about it until until years later. In its own way, that was a very special event, and an interesting unification of black and white participants on both sides of the stage.”

“[The Shell] was a place to create this community that hadn’t really existed before,” Palmer says. “It still feels aspirational to have people of all races together celebrating American culture. It happens sometimes, but it doesn’t happen all the time.”

If you’re interested in the Memphis Country Blues Society you can read more in this week’s Memphis Flyer cover story. The Levitt Shell has been given another extraordinary (and necessary) facelift. Instead of just cataloging all the fantastic improvements I wanted to present them on the context of an amazing cultural resource that we almost lost more than once. Not to take anything away from the Levitt Foundation — the heroic cavalry of this story. But the Shell’s decline is closely related to a story of shifting cultural attitudes, and we owe a lot to folks who kept it standing when others wanted to turn it into a parking lot.

Also, if you’d also like to help Palmer make her documentary about the Memphis Country Blues Festival, there’s still time to donate to her Kickstarter campaign.

MLB.com

MLB.com