Jon Logan was not feeling his best after a night listening to the blues on Beale Street. Needing a breath of fresh air, he laid down in the middle of the street. It was then, as he gazed from side to side, that he spotted a lit window featuring black-and-white photographs.

“At that point I had a conversation with myself,” he says. “Am I here for the music? Which I don’t get to see enough of. Or am I here for black-and-white photography, which is another love of mine. I wanted to go back to the clubs, but there was something that drew me to the front of the gallery. And as soon as I saw the photo of Dr. King, and then Tina Turner, and the Negro Leagues, I just had to go in. It happened to still be open. At 11 p.m., they were preparing for a party the next day.”

It would prove to be one example of the role serendipity has played in the preservation of famed photographer Ernest C. Withers’ legacy. For Logan was not just another tourist curled up on the pavement — he was the head of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation.

“I grew up in a family of collectors of black-and-white photography,” he says. “So it’s in my blood.” As he discovered the breadth of Withers’ work that night, he began talking fervently with Rosalind “Roz” Withers, the photographer’s daughter and the trustee of his estate. “I presented my credentials in photography and art, and we started talking about the collection. And somewhere around midnight, she took me to see the archives.”

© The Withers Family Trust

© The Withers Family Trust

Ernest Withers in Little Rock, 1957

Stacks of boxes, containing Withers’ life work since the 1940s, were scattered in disarray. “It was at that point I realized, ‘Well, I have some expertise in this field. And there’s many thousands of negatives and photographs that really need help.’ So that’s when I told Roz, maybe we should think about working together.”

The collaboration they imagined four years ago marked a turning point in the collection, helping to take the archive one step closer to becoming a world-class facility. With an estimated 1.8 million negatives and prints, it’s a daunting task, which the museum and archives, previously self-funded through sales of prints, was ill-equipped to tackle.

Once Logan’s foundation entered the picture, the archive could hire and train a staff. “My immediate concern was how they were stored and how to teach them a little bit more about conservation before we got into the archival side,” says Logan. “I really wanted to have pros come in to help. And we happened to find this great group in Philly, the Conservation Center for Art and Historical Artifacts (CCAHA).”

After several visits from CCAHA, the staff was ready to manage the archives far more effectively. At last, Ernest Withers’ legacy was getting its due.

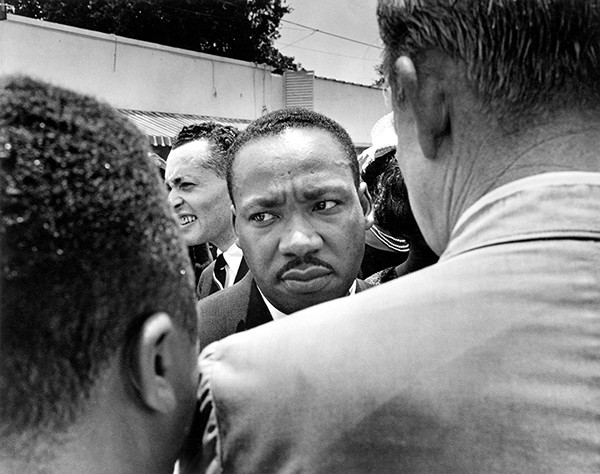

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

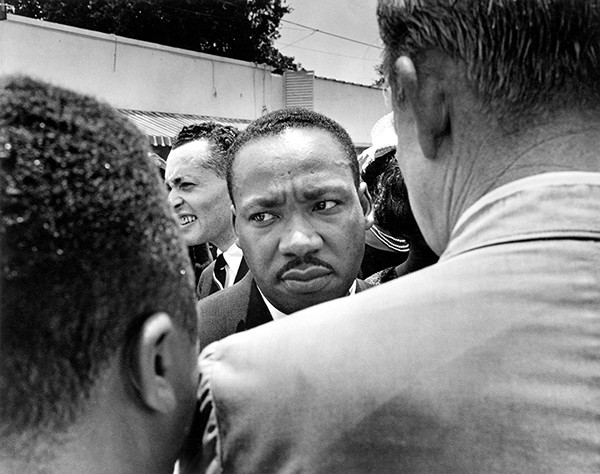

MLK at Medgar Evers’ funeral

But what is that legacy, exactly? Though Withers produced many iconic images of civil rights leaders, musicians, and the Negro Baseball League, he did not receive recognition comparable to, say, Gordon Parks, until later in his life. Unlike Parks, he never worked in glamour photography, much less cinema. Indeed, it seems that making ends meet was always a struggle for Withers, possibly because his images circulated largely in the black press. For decades, his bread and butter came from his small Beale Street studio, photographing weddings, funerals, and other social functions. Deeply committed to his community, he never left behind the less glamorous work that his craft was rooted in, and he never really left Memphis.

Author Preston Lauterbach, whose forthcoming book, Bluff City, focuses in part on Withers’ place in Memphis history, notes that he grew up in a very community-minded family. “His family was really involved with stuff. His father ran a voting registration and polling place out of their home in North Memphis. And his father had a high-status, high-connection job. And so he was definitely an operative of the African-American Republican machine, which also collaborated and participated with the Crump machine. So he was part of everything here.”

Rosalind Withers fills in some of the details: “My father grew up on Manassas. And their home was torn down to make a parking lot for the church that he grew up in — the Gospel Temple Baptist Church. It’s still there. His father was a postman, and he wanted his son to be a postman. His brother was an attorney; he had another brother that was a pharmacist, and they migrated to Washington, D.C. … But my dad was the picture-taker. So he wasn’t really considered to have the career that his brothers had.”

Nonetheless, Withers was enterprising. His sister gave him a Brownie camera while he attended Manassas High School, and he made the most of it. “Marva Trotter-Louis, Joe Louis’s wife — she was a Halle Berry lookalike — came to the school. And my father was not on any yearbook committee or anything. But he got the courage, went up front, took pictures of her, and became the most popular guy in school, because everybody wanted a picture of her. So that was the bite that got him.”

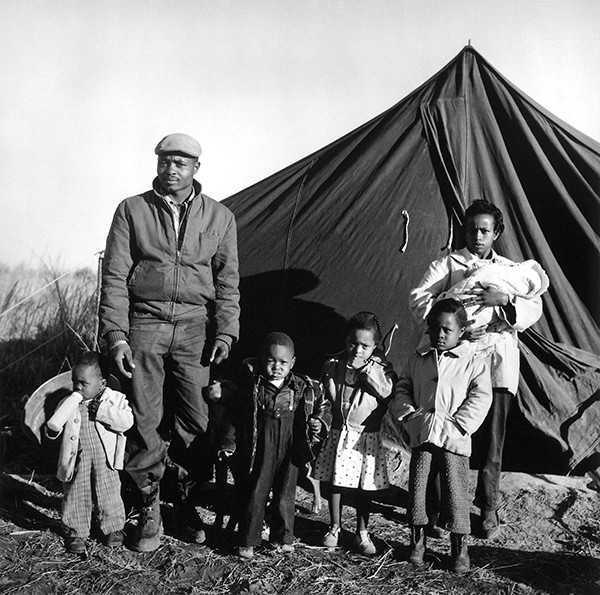

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

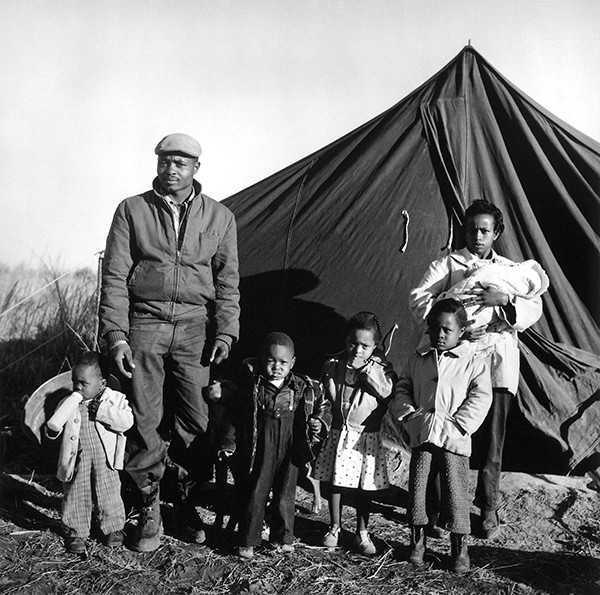

Operation Tent City, a major voting rights story from Fayette County that Withers covered for Ebony

While stationed in the Pacific during World War II, Withers jumped at the chance to work in the photography lab. “And when he learned how to develop in the army,” Rosalind recalls, “he would take pictures of the soldiers, develop them, and they would have pictures of themselves on this beautiful beach. He would get rolls of money, put it into the little canister that the film came in, and send it home to my mother. And she was getting these rolls and rolls. And see, that was the bite for her. So when he came back home, they thought, ‘How do we do that here?’ So, they started taking pictures at the Negro Baseball games. That’s when she began to help him. Because she would dry them in the oven.”

From that point on, Withers was grounded in the local African-American scene. “He has 1.8 million images that we’re trying to digitize, archive, and identify,” says Rosalind. “And the largest body of work of that is the lifestyle material. … He was the community photographer. He covered social events. He covered civic events. And my father was always in churches. I mean we have the history of most of the churches in all of the communities.”

While the end result is a stunning social history of black Memphis, the photos haven’t bolstered his reputation as a fine art photographer. But with a new exhibit at Crosstown Arts, Rosalind hopes to change that.

While there are a few gripping images from the struggle for civil rights, most are of anonymous Memphians. “We don’t really have captions because we want people to come tell us, ‘That’s my cousin. That’s my brother. That’s a relative.’ We want them to tell us who’s in these pictures. We also plan to travel with this exhibition.”

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

Withers was also the official photographer for Stax Records’ Carla Thomas

The support of the Logan Foundation is expected to lead to wider recognition of the sheer breadth of Withers’ work. “We want to continue to raise the awareness that this is a world-class collection,” says Logan, “and that it’s worthy of being in museums and private collections.”

Still, Withers’ most renowned works remain his civil rights photojournalism, which the Logan Foundation and the Withers Museum have prioritized. Thanks to the new funding and training, 12,000 previously unseen civil rights images have been archived and digitized, and will soon be available online in a searchable database.

Meanwhile, at the Brooks Museum of Art, some of Withers’ previously known works are being shown, using a handful of images curated in the late 1990s for a traveling exhibit and book, Pictures Tell the Story. This period marked the beginning of a greater appreciation of Withers’ work. The entire collection was ultimately purchased by the Brooks Museum. Yet the collection of newly digitized civil rights images dwarfs this earlier curation, expanding the sheer volume of his photojournalism a thousandfold.

What makes Withers’ civil rights work so compelling is its combination of intimacy and daring. His life of community involvement and activism was strictly regional, but it placed him in the heart of the national civil rights movement, enhanced by his personal connections and his work ethic.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Roz Withers, caretaker of the archives

As Lauterbach notes, “Withers was covering the Emmett Till trial, which is its own incredible story; Withers was covering Montgomery, which is its own incredible story. Tent City, which was a major, important story that a lot of people don’t know about, Withers covered. And then of course he continued working throughout the Medgar Evers story. He went down to Philadelphia, he was in all of those hot spots. He was there, he was risking himself. He was arrested in Memphis doing his job at a Walgreens sit-in in 1961; he was beaten and arrested in Jackson, doing his job as a photographer at Medgar Evers’ funeral in 1963; and he continued to put himself in risky situations.”

This is clear in one photo in the Brooks exhibit, “Policemen in Riot Gear, March 28, 1968.” A phalanx of officers runs along the street, in riot helmets and gas masks, but one is closer to the camera than the rest, his glowering face and raised baton promising imminent danger to the photographer. As a portrait of unbridled hatred, it is without parallel. One shudders to imagine Withers’ resolve in holding his ground long enough to capture it.

The commitment apparent in Withers’ civil rights work made it all the more inflammatory when reporter Marc Perrusquia, working for The Commercial Appeal, published evidence in 2010 that Withers was a paid informant for the FBI during the 1960s. One historian called it “an amazing betrayal.” Interest was so great that Perrusquia ultimately published a book on the matter, A Spy in Canaan: How the FBI Used a Famous Photographer to Infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, which was released last week. As a tale of investigative journalism, it is a powerful read: Gaining access to the FBI files on Withers required dogged persistence, and ultimately yielded hundreds of pages of documented meetings between Withers and local FBI agents.

But most of the people who worked with Withers at the time remain unfazed by the revelations. Reviewing the FBI dossier, it is difficult to ascertain any concrete harm that Withers did to civil rights organizations, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), or local activists the Invaders, through his FBI reports. The New York Times quoted Andrew Young, who was a prominent member of the SCLC, as saying “It’s not surprising. We knew that everything we did was bugged, although we didn’t suspect Withers individually.” Indeed, Young has stressed that SCLC was transparent to a fault, feeling they’d be less endangered if the FBI was kept apprised of their activities.

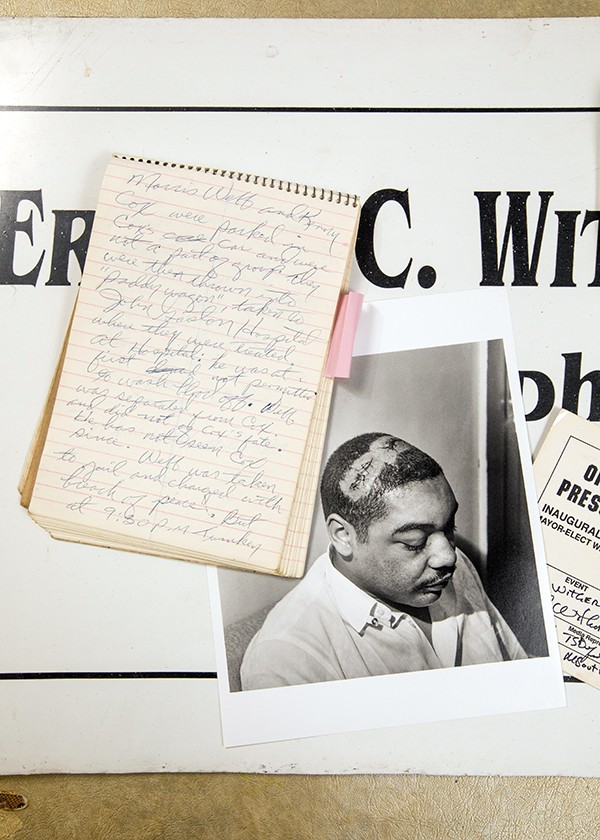

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

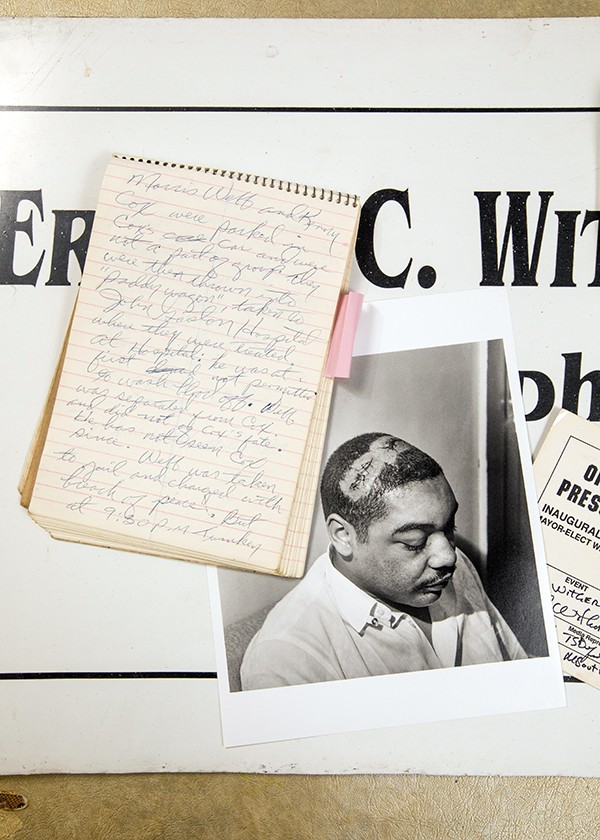

A reporter’s notebook, found in the Withers archives, details the beating of Morris Webb on March 28, 1968, alongside Withers’ image of Webb from that day.

Withers’ reports to the FBI, while giving some information on SCLC meetings, focused largely on the personal relations and foibles of local black activist group the Invaders (chronicled in a documentary film by Prichard Smith). Thinking that former Invaders, if anyone, would feel the greatest sense of betrayal at the hands of Withers, I spoke with onetime Invader John B. Smith, now residing in Atlanta.

“That son of a bitch!” Smith said of Perrusquia. “He’s making a living, trashing Mr. Withers. But Mr. Withers deserved admiration. Most people don’t recognize that he put his life on the line getting a lot of those shots. Traveling by himself to places where things happened that white people in the South did not want reported. So it wasn’t like he was a paparazzi or some bullshit like that. This man was a very serious scholar, and he worked to bring truth in the face of a horrible history. I think he deserves a statue somewhere.”

If Perrusquia’s book stirred up resentment by seemingly redefining the life’s work of a heroic figure, it also left many wondering what motivated Withers’ involvement with the FBI. Given the paltry fees he received for his photojournalism, it’s no small matter that the feds paid him well. We also have Withers’ own admission of his involvement, when his work first began to get wider recognition in 2000. “I always had FBI agents looking over my shoulder and wanting to question me. I never tried to learn any high-powered secrets. It would have just been trouble. I was solicited to assist the FBI by Bill Lawrence who was the FBI agent here. He was a nice guy but what he was doing was pampering me to catch whatever leaks I dropped, so I stayed out of meetings where real decisions were being made.”

Lauterbach also believes we have to consider the possibility that Withers saw the federal agency as a protection of sorts against local police. “There was this outcry: Where was the federal involvement in the Emmett Till case? People were pissed off about it, and called Hoover to task. Then you jump to Little Rock, where the federal support really did arrive. Well, Withers was in both of those places, so he understood the contrast, and a potential for federal help that was new. And by the time you get to Tent City in 1958-60, you have black journalists, among them Withers, who published photos from Fayette County in Ebony magazine, and Memphis office FBI investigators blowing the lid off a voting rights discrimination case.” Indeed, Withers subsequently reported the police brutality he suffered in Jackson, Mississippi, to the FBI in 1963.

In any case, the revelations about FBI involvement, while casting a new light on FBI operations in Memphis at the time, seem destined to be a footnote to the undeniable power of Withers’ work. As Lauterbach notes, “I think his level of risk and sacrifice for taking photographs for publication of those stories is a fair balance to whatever people might suspect his FBI involvement means.” The risk — and the commitment — is palpable in the images.

Soon, in addition to the revamped archives and plans for traveling exhibits, the Withers legacy will receive another bump of recognition with two films now being developed. Phil Bertelsen, whose film Chisolm ’72 won a Peabody Award, has been shooting in and around Memphis for a documentary on Withers’ life.

And, as Rosalind explains, a feature film, 68: I Am a Man. The Sanitation Workers’ Story, is also being developed, “along the same lines as Selma.” And this week, the film’s producers will gather people from all over the world to stage a recreation of Withers’ famous “I Am A Man” image, now expressing an international diversity.

Once that photograph is snapped, it will be further proof that Ernest Withers’ Memphis legacy has gone global.

Note: The Withers Archive also recently yielded a striking, detailed account of King’s first March on Main found in a notebook of a yet-identified writer.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Memphis Rox

Memphis Rox

© The Withers Family Trust

© The Withers Family Trust  © Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust  © Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust  © Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust

© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue