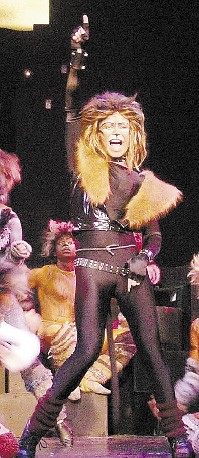

Lupita Nyong’o as Red in the climax of Us.

Jordan Peele’s provocative horror film Us is on track to break $100 million at the box office in its second weekend. It seems to be one of those rare moments when commercial and artistic success line up. I talked over coffee with Dr. Marina Levina, a scholar of horror at the University of Memphis’ Department of Communications and Film about the Us phenomenon. We went on at great length, so I was merciful and edited our conversation for clarity and (relative) brevity.

Do I have to say there will be spoilers? Because it’s wall-to-wall spoilers, so this conversation is best consumed after you see the film.

Dr. Marina Levina

I was excited to see this movie. I went to see it on opening night, because I knew my film students would want to talk about it immediately. On Monday, most of them did. They went to see it on opening weekend. It’s what everyone’s seeing and talking about. My Facebook page, which is my colleagues, media studies professors from all over, that’s all anyone is talking about.

Chris McCoy

It’s literally in your wheelhouse.

ML

I teach horror and monster films, and I write about monstrosity. It’s an interesting movie. It gave me a lot to think about it. It’s not as clear cut as Get Out. It’s more experimental. There were parts of it that worked for me, and parts of it that didn’t work for me. But it’s definitely something I’m thinking about every day.

CM

Me and Laura, my wife, have talked about it nonstop. I’ll wake up and we’ll have coffee and she’ll be like, “So, in Us…” What makes it so interesting?

ML

First off, it’s Jordan Peele, and Get Out was such a breaking point in the horror genre. A horror movie with a black filmmaker is significant. Unfortunately, that’s still significant. A horror movie that addressed the question of race in America, in academia, that’s all anyone was talking about for years, and still are. That sound you hear is dissertations being written about Get Out. And now you can add Us. The expectations were super high. It’s one thing to make a horror movie that’s scary. It’s another thing to make a horror movie with ideas and analogies. Academics always like those movies. For me, it was not a scary movie. But then again, I am very hard to scare at this point. I’m sure other people found it more jumpy. What was interesting to me is, I hate the home invasion genre. It is the only genre of horror movies that genuinely spooks me. It gives me heebe jeebies. I avoid them as a rule, and I was kind of leery about going to see Us, because it looks like a home invasion movie. But it really wasn’t a home invasion movie. It was something different.

CM

It was like he was cycling through horror subgenres every fifteen minutes or so. It’s like a home invasion movie, but it’s an awkward dad comedy for fifteen minutes.

ML

Peele’s movies are genuinely funny. But it’s interesting that it sort of displays the question of race in some way, shape, or form. I guess the race of the characters is important. But that’s not the point. It is important how unimportant it is. It is definitely subversion in a horror movie for black characters to be a well-to-do family. Usually, you see those characters in an impoverished area with gang violence. This is an upper middle class family who can afford a summer home and a boat, who hangs out in Santa Cruz, which is super white. I used to go to Santa Cruz. I loved that it was Santa Cruz, because it’s the same roller coaster from The Lost Boys…there are references to the 80s throughout the movie.

The boardwalk in Santa Cruz, California as seen in the 1986 vampire horror classic The Lost Boys.

It engages race, but at the same time it displaces race. At some point I was expecting to see that the white characters didn’t have a Tethered. It would only be the black characters who had a Tethered. But when everyone did, it was really, really surprising. To me, the best way to think about this movie is as a companion piece to Sorry To Bother You. I think there are certain similarities, with the black people being immersed in white culture—the “white voice” that sort of permeates these black characters lives…Someone pointed out that they didn’t have any questions about calling the police. I kept waiting for the moment when it became a thing, but it never became a thing.

CM

Because that’s not what this movie is about.

ML

It’s such a subversion of expectations…In Sorry To Bother You, it’s a more overtly political critique of capitalism and the white establishment.

CM

It’s more overtly science fiction as well.

ML

It has that same sort of surreal element. In Sorry To Bother You, you have these horse people who are underground. In this, we have the Tethered. Who created them? It’s never really explained. But who would have the money? Who would it benefit? There’s this larger conspiracy framework to it.

Whatever we’ve built, we always built on the backs of others. It’s easy to say that these others are people who we don’t have to pay attention to. But they’re not. They’re us. At any moment, it could be us. The flip at the end, that’s what that’s indicative of. It is us on whose backs everything is being built.

CM

We think we’re the upper class, but we’re really not.

ML

Do we really think that any more? I keep trying to think of this movie in the context of the Trump administration. I don’t really know what to make of it in that context, but I think it’s like when [Lupita Nyong’o] says, “We are Americans”.

CM

It drops like a bomb at just about the middle of the movie.

ML

I think it’s definitely about exploitation and otherness. Whatever it is that’s happening, this Make America Great Again. It’s about the myth of this nation, its success, built by the strength of individuals, is not really true. It’s always, perpetually, in a capitalist system, about the exploitation of others. I think that’s where he was going with it. I don’t think it was always clearly articulated enough, almost on purpose, but it’s this idea that we think we are not the oppressed, but we are. We don’t think we oppress anyone, but we do.

CM

I’m not sure he really knew what he was doing—and that’s when the best art happens. We don’t know, and authorial intent doesn’t really matter. But I think the best art comes when the artist is pursuing an idea that they don’t fully understand. You discover what the meaning is, for yourself and for everyone else, during the process.

ML

That’s the work that media scholars like myself do. It’s something I tell to students. This is not auteur theory. We don’t really care about Jordan Peele’s intentions. But it’s interesting to consider. He’s in a unique position as a black man in Hollywood. He himself becomes a part of the text.

Right now, I am writing a book on cruelty. I just got my research assistant to collect everything written on Us in the last week. I think it’s going to become part of the book. What do we do to others when we don’t think about it?

CM

Who do we have permission to be cruel to?

ML

Yes. And what is considered to be cruel? That’s how I’ve been thinking about it. Not every act of violence, not every law, not every discourse, is considered to be cruel. What is the cultural thing that happens that makes a certain act cruel? For example, when we talk about border policy, and we’re locking kids in cages. People are saying, Oh my god, this is cruel? And it is. But you know what is really cruel? Locking human beings in cages. It shouldn’t just be about kids. It should be about human beings. But it’s cruel because it’s kids. Others, we’re OK with that. We have a system of mass incarceration that locks adults in cages, and we are cool with it. But not kids. We have these delineations in society about whose lives matter and whose doesn’t. Whose experiences are validated and whose aren’t. And I think that’s what Us is fundamentally about. To whom can we do what things to? At what point does it come back and bite us in the behind?

YMCA

YMCA

Jerry’s, Facebook

Jerry’s, Facebook

TDOT

TDOT  National Community Reinvestment Coalition

National Community Reinvestment Coalition