As COVID-19 rampages through the country, its effects are disproportionately affecting people in disenfranchised communities — those living in poverty, the undocumented, certain African-American neighborhoods — and the children in these communities. Issues of low wages, lack of access to medical care, and educational disadvantages have existed for years. Now the coronavirus pandemic is magnifying these problems and bringing them to light. Here’s a look at how COVID-19 has impacted the less fortunate among us.

Dr. Elena Delavega

Poverty in a Pandemic

For those living in poverty, Dr. Elena Delavega, a professor at the University of Memphis and an expert in poverty, says the pandemic has “tremendous implications on a number of fronts.”

Memphis has a poverty rate of just under 28 percent, according to the 2019 Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet compiled annually by Delavega and others at the U of M. That’s more than double the 11 percent poverty rate for Tennessee and the 12 percent rate for the country.

“From health care, to the ability to work from home, to accessing protective gear and other necessary supplies, to education, the effects of poverty are only being highlighted now,” Delavega says.

As more people are laid off or furloughed, Delavega notes that the ability to withstand a furlough depends largely on one’s savings. But, she points out, people living in poverty often don’t have savings. This means they don’t have the financial resources to buy supplies and food in bulk. “They can only buy what they need, little by little. Now they are going to the store more often and facing more exposure. And if there is a disruption in the supply chain, those who aren’t able to stock up on resources will be most impacted.” An issue that Delavega says can no longer be ignored is access to health care. Because health care is often tied to jobs in the United States, when people lose their jobs, “they are essentially being condemned to death.” Delavega adds that many who hold essential jobs, such as fast food and grocery store employees, don’t have access to health insurance through their employer.

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

“One thing we’ve seen in South Korea is that everything was made available to everyone,” Delavega says. “Here, we don’t do that. Wealthy people have access, while poor people don’t. In Europe, we’ve seen a triage based on who has a greater chance of survival, but here that triage is economic. The priority is not given to those with a greater chance to survive, but to those who can pay for medical services.” Delavega also notes that those who are living paycheck to paycheck must continue to work, whether they are sick or not. “People in poverty can’t afford to avoid the virus. They have to work. They have to eat.”

Tiffany Lowe, an employee at a local Kentucky Fried Chicken who joined other fast food workers in a strike to protest unsafe working conditions amid the COVID-19 outbreak in early April, knows the struggles cited by Delavega firsthand. Lowe has been working at KFC for three years and makes $8 an hour.

“I have a son with an immune deficiency disease, and I’m afraid one day I’ll bring home the virus to him and he’s not going to be able to fight it off,” Lowe says. “I’m frustrated, angry, and confused as to why a multi-billion dollar corporation such as KFC wouldn’t give us the things we need to survive like hazard pay, health care, and paid sick leave. I mean, if they want to call us essential employees, then they should make us feel essential, treat us like human beings, and give us what we deserve.”

Lowe says the company is also putting customers at risk, as employees who are sick are likely to still show up to work because there is no paid sick leave.

“This job is the only source of income for a lot of us,” she says. “So without working, how would they survive? Some people might come if they’re sick, putting people’s lives at risk.”

Delavega says people in Lowe’s position, living in poverty, making little above minimum wage, have always been in danger of losing their livelihood and lives when a crisis occurs.

“The reality is in the American society, the lives of poor people don’t really matter.” she says. “These things aren’t new. The pandemic is just highlighting conditions that already exist. The crisis has made it obvious. We’re seeing it on a grand scale.”

This is the reality for poor people every day, she says. “One disease, one tornado, one case of bad luck for the business they work for, and this is what happens. This is true for nearly 200,000 people in Memphis. Every single day. When this is over, are we going to remember the most vulnerable among us? Are we going to remember the need for universal health care and a livable wage? Are we going to recognize the importance of internet access and make it a public resource? It’s not a luxury, but an essential utility.”

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Children Will be “Most Impacted”

Children living poverty will be the “most and worst impacted,” Delavega says, citing the education gaps closed schools and remote learning has created. Nearly half of the children in Memphis, or 44.9 percent, live in poverty.

“They are essentially missing a half semester of learning,” she says. “Students living in wealthy homes with computers can continue to study. They have the books and the resources to continue learning. Families without computers or the internet are simply not going to be able to continue that education.”

She says for those children the school year has essentially ended, and Delavega fears they will be at a disadvantage at the beginning of next school year. “If students lose knowledge over the span of summer break, imagine how much more they are losing now and how much more academically disadvantaged they will be next year.”

Delavega fears the impact of COVID-19 on children living in poverty will be “permanent and long-lasting. The educational impacts will follow them for the rest of their lives.”

Katy Spurlock, with the Memphis Interfaith Coalition for Action and Hope (MICAH) education equity task force, says MICAH sees greater inequity in education “than we do anywhere else. We’re focused on bridging the gap.”

With schools closed, Spurlock agrees that the greatest issue for students in impoverished communities is the lack of internet access and devices. “There is a huge divide there. Children whose families have internet access and devices or go to schools that provide them are a step ahead. We’re just trying to work to hold the community accountable to make sure that need is met.”

Census data shows that in the South Memphis and Washington Heights neighborhoods more than 80 percent of households have no broadband internet access. In Frayser, 63 percent of households are without internet access.

A report by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance published in 2018 found that of the 256,973 households in Memphis in 2016, 126,428 of them had no broadband connection.

Spurlock says, “We’re already behind the eight ball realistically in this community with education and being able to successfully matriculate students through the school system. We already had problems with disparities before COVID-19.”

However, Spurlock says she is going to be optimistic about the outcome of the pandemic for students. “I’m going to say we’re going to be able to get this right and at least not make things worse, to ensure that children get the access they need to continue to be able to learn. When we start back school in the fall, creative thinking will prevail. I see this as an opportunity to get things right.”

Alexis Gwin-Miller, who also serves on MICAH’s education task force, says this crisis presents a “wide-open door for equity to rise. We don’t have to stay in a place of disparity.” She says it is an important time for collaboration across socioeconomic lines to address equity “for all students, no matter where they live.” She also calls for the use of concrete data to deploy resources where they are needed, explaining there should be a priority to provide internet access in ZIP codes with the least amount of connectivity.

To bridge the digital divide, Shelby County Schools is working on a new plan to provide students with devices and internet access. A draft of the plan, including three options, was released in April and awaits approval from the school board. The initial cost of investment for the three options ranges from $22.2 million to $77.3 million. The options vary from providing all 94,691 students with devices equipped with the internet to only those who are eligible for free or reduced lunch.

If approved, the distribution of devices would begin within 30 to 90 days, depending on the option selected, which leaves little time to bridge the gap left in this school year scheduled to end on May 26th.

The ‘Invisible’ Community

Mauricio Calvo, executive director of Latino Memphis, says the struggles of the Latinx and immigrant community have been threefold amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Latinx people are just like everyone else,” Calvo says. “We have the same fears and emotions, and on top of that, are struggling, as many people in poverty are, and then on top of that, there are barriers that come when you are an immigrant.”

Calvo says from the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in Memphis, “There’s been an invisibility of our community. I know it wasn’t intentional, but I think in the midst of the crisis, there hasn’t been an effort to reach out to subgroups. It’s been more of a one-size-fits all response.”

For the Latinx community, Calvo says the pandemic has highlighted specific challenges already present, such as the language barrier and lack of access, trust, and health care.

Cecilia Martinez, a caseworker for Latino Memphis, says she works directly with Latinx clients and one of the main concerns is getting accurate information in their language.

“For example, the shelter-in-place information hadn’t been correctly translated to say what it really means to say,” Martinez says. “If you don’t know what’s going on from the beginning, that makes it harder to get ahead. A lot of the time the information comes in English, and it’s usually not translated until someone brings it up.”

Martinez notes the hardest population to reach is those who speak dialects of Spanish not widely spoken, such as the Guatemalan community. “It’s hard enough to get things in Spanish, but even harder to get them in more specific languages.”

The lack of health insurance is another obstacle Calvo says the immigrant community faces. “If you are undocumented, you can’t get health insurance. This is a real issue among older Latinos. People worry about getting tested and being positive and not knowing what to do next. Some worry about getting tested in the first place because of what documentation they’ll be asked to provide.”

Calvo says the undocumented community, like many impoverished populations, is also facing financial challenges. “The stimulus payments only benefit taxpayers who have social security numbers. This is very unfair, and it’s important to know that there are many, many people who do not have social security numbers and still pay taxes and who are parents of American children. But these people were still left out of the stimulus package.”

The government is leaving people behind who are a part of the economy, Calvo says. “We can’t pretend these people aren’t a part of the economy. There are hundreds of people feeling left out. These people are humans, Memphians, and taxpayers. It’s a matter of representation.”

Duane Loynes Sr.

Health Disparities

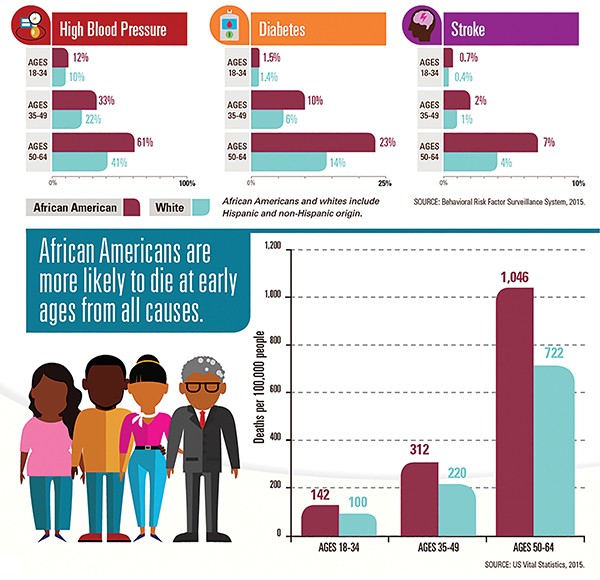

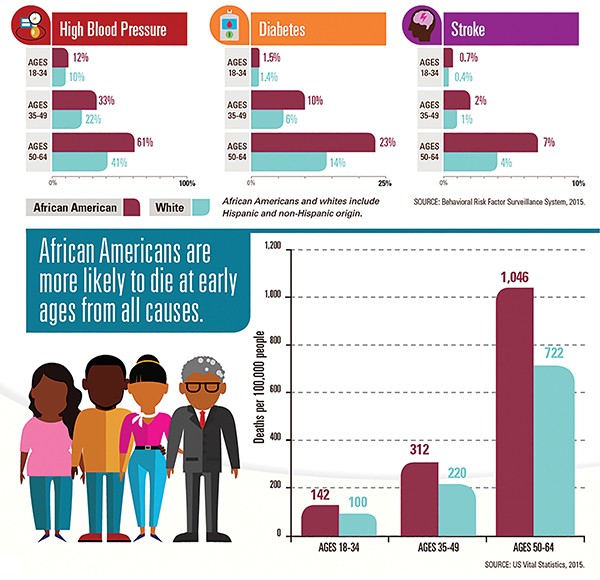

Preliminary data suggest disproportionate effects of COVID-19 among racial and ethnic minority groups, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted in a recent report.

One of these racial groups is African Americans. While blacks represent only 13 percent of the U.S. population, nearly one-third of people diagnosed with COVID-19 nationwide have been black, according to CDC data. (Race has only been reported in 42 percent of cases.) Similarly, nearly one-third of those who have died across the country are black, notes a recent analysis by the Associated Press using available state and local data.

While blacks make up 52 percent of Shelby County’s population, 68 percent of the county’s confirmed cases where race was reported are African-American. The county has not released demographics for the 44 deaths recorded here.

Duane Loynes Sr., assistant professor of urban studies and health equity at Rhodes College, says he is not surprised that COVID-19 has “ravaged” the African-American community. By design, he says African Americans are a socially vulnerable class.

Those living in the 38106 ZIP code near the Soulsville area have a life expectancy of 13 years shorter than those living in the Collierville ZIP code of 38107, Loynes says. “When you drive the short 30-minute drive from Soulsville to Collierville, the life expectancy ridiculously increases.”

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Loynes points to scientific reasons for this disparity and behind why African Americans might be more susceptible to contracting COVID-19 and ultimately dying from the disease.

When one is stressed or fearful of danger, Loynes says their body produces excess cortisol, a long-acting hormone. Preparing one to fight or to take flight, cortisol does three key things in the body. It raises one’s heart rate to prepare the body to take in more oxygen, thickens the blood in case of injury to slow blood loss, and slows down one’s insulin response to give the body more energy.

“It’s really a genius way our bodies are designed, but it’s designed for occasional usage. But suppose you live in a world where you’re poor or African-American and you’re constantly worried about how you’re going to pay your bills, how your children will get a good education, that you’ll be evicted, or about law enforcement. Your body is constantly doing something we’re not designed to do — putting cortisol into your body.”

Loynes says an increased heart rate, thickened blood, and slowed down insulin correspond perfectly with three health issues African Americans are more likely to have than others: diabetes, stroke, and heart disease. “If your body is under stress and having to adjust to it, these are the consequences.”

Another health issue more prevalent in African-American communities is asthma, he says. “We understand that there is a direct correlation between communities of color that struggle with asthma and waste sites. Black folks tend to live in close proximity to toxic areas. We see this all around the country.”

This is not incidental, Loynes says. “I’m not saying someone said ‘Hey, let’s do this to African-American communities,’ but the disregard for black life has made black communities vulnerable, and that makes all these other things worse. Because of these underlying health conditions on top of everything else, when COVID-19 comes on you, the body is already under significant stress.”

In a press conference in early April, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, who is African American, discussed blacks’ higher risk of contracting COVID-19. In his statement, Adams urged black Americans to “step up” and stop behaviors such as smoking and drinking to curb the spread of the virus among blacks. Loynes says Adams had good intentions, but “he talked in a way that blamed African Americans for why they may be more at risk. He said things like ‘tell grandma and them not to smoke or cut back on this or don’t drink the alcohol.’ But it’s very clear all the ways racial bias leads to health disparities. But we don’t like to talk about it. We’d rather blame big mama and say stop smoking. That’s not the point.”

Loynes says white Americans or those living in wealthy communities can afford to partake in bad behaviors because they are “born farther away from the edge. White people drink and smoke as well, but they’re not dealing with the same issues. The consequences aren’t as dire. The difference is they have a safety net. African Americans are born at the edge, and one mistake is it for us.”

It all points back to poverty and structural racism, Loynes says. “I’m not saying African Americans are perfect. We all need to make better decisions. But the big picture items we struggle with are not our fault. They are structurally designed that way.”

Loynes says fixing the structural issues and the resultant disparities that exist in U.S. society won’t happen overnight. “We have to remember it typically takes longer to fix something than it does to break it. The problems that we are dealing with have been in existence for 401 years. We have to change the structural realities. We have to roll up our sleeves and get ready for multi-generational work.”

Dining With Myself/Facebook

Dining With Myself/Facebook

Joseph Jones Photography

Joseph Jones Photography

Julie Song

Julie Song

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Richard Murff

Richard Murff