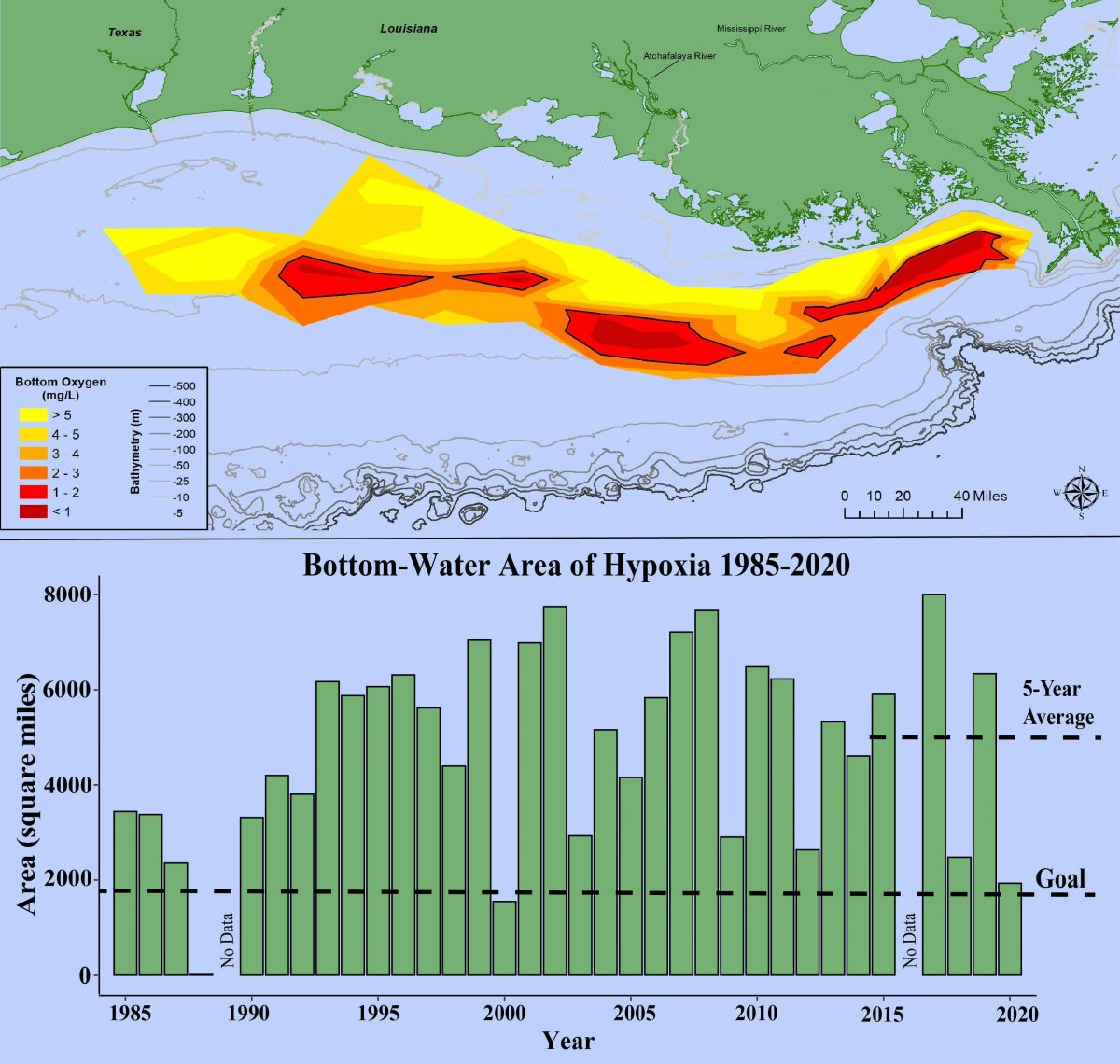

Scientists have collected data on this annual dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico since 1985. But for the last four years, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminstration (NOAA) have focused on the Gulf’s dead zone where oxygen levels are low and predicted its size.

This year’s zone is smaller than the five-year average of 5,400 square miles and nearly half of the 2017 record zone of 8,776 square miles. But at 4,880 square miles, the zone is not small — it’s comparable to the state of Connecticut’s 4,849 square miles.

The dead zone is primarily caused by excess nutrient pollution from human activities in urban and agricultural areas throughout the Mississippi River watershed. When the excess nutrients reach the Gulf, they stimulate an overgrowth of algae, which eventually die and decompose. This depletes oxygen in the water as they sink to the bottom.

The resulting low oxygen levels near the bottom of the Gulf cannot support most marine life. Fish, shrimp, and crabs often swim out of the area, but animals that are unable to swim or move away are stressed or killed by the low oxygen. This dead zone flows west from the tip of Louisiana and hugs the coast.

Most of the pollution that creates the dead zone arrives there by the Mississippi River watershed, which encompasses 40 percent of the continental U.S. And cross 22 state boundaries. That’s how Tennessee contributes to the dead zone, sending mainly agricultural runoff (like fertilizer) and treated human waste down the river. All along Tennessee’s river coast — including Memphis — treated human waste is the biggest source of pollution followed by fertilizer, according to data from the United States Geological Survey.

Memphis now operates under a 2012 federal consent decree after a number of agencies alleged the city illegally allowed its sewer system to overflow into the river. In 2016, the city’s system spilled millions of gallons of untreated wastewater into the Mississippi. The city is now working toward the end of the 10-year Sewer Assessment and Rehabilitation Program (SARP10) program to update the sewer system.

“Like many other cities, Memphis has an aging wastewater collection and transmission system that consists of buried pipes, manholes, and pumping stations,” Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland says on the SARP10 website. “In fact, parts of our system are more than a century old. Due to age, our sewers have experienced some deterioration.”

The federal Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force is also working to reduce the size of the dead zone to a five-year average size of 1,900 square miles.

“Through state leadership in implementing nutrient reduction strategies, support from [Environmental Protection Agency – EPA] and other federal agencies, and partnerships with basin organizations and research partners, we will continue to tackle the challenge of Gulf hypoxia,” said John Goodin, director of the EPA’s Office of Wetlands, Oceans and Watersheds.