Day after day this summer’s heat indexes are topping 100, and this August is one of the driest, hottest, muggiest months on record. Instead of trying to beat the heat, David Mah decided to accentuate it with “Erotica 2006,” an exhibition/full-frontal assault on the funny bone as well as the erogenous zones.

Forty-nine artworks by 25 artists include paintings of Barbie in leather, a peephole (with a footstool for voyeurs 5’2″ and under), black-and-white photographs of nude Adonises and Venuses, and a beautifully crafted designer set of 11 milk-white phalluses all bending toward a small round opening at the center of Bryan Blankenship’s ceramic installation Wishing Well.

Mel Spillman’s It’s Alright If You Love Me, It’s Alright If You Don’t lies at the crossroads of pornography and fine art. A fine grade of untouched paper suggests flawless alabaster skin. Pools of red for nipples and a wide-open mouth, a lemon-yellow wash for hair, and a few fluid strokes of gouache and iridescent ink for nostrils, eyebrows, a collar bone, and the edges of the breasts complete Spillman’s vision of purely physical, no-strings-attached erotica.

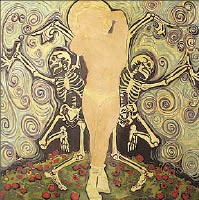

This exhibit is not just unabashedly sexual. It’s campy, philosophical, and it broaches the ineffable. In Tim Andrews’ Eros and Thanatos (oil and acrylic on canvas), a youth in a field of red poppies is surrounded by Van Gogh-like swirls. He cradles his head with his hands — a gesture that suggests a flood of feeling and Eros’ tenderness as well as his passion. Crowned with a Byzantine halo, his lithe pink body glows with an inner light that blurs his features. Skeletons leaping with abandon beside the youth (a kind of memento mori) suggest that at transcendence, the physical and spiritual passions, rather than splitting off, are partners in a dance of remembrance and joy.

The subject of Jane I by Jack Robinson (silver and gelatin print, circa 1960s) is borderline anorexic and pushing 30. She straddles a chair that is as reed-thin as her limbs.

Eros and Thanatos by Tim Andrews

The curve of her back and ribs is repeated in the frame of the black bentwood chair. Dark shadows and ebony wood contrast with fair skin, blond hair, and light reflecting off ribs. Robinson’s repeated curves and contrasts create a strong image. The stories Jane I suggests are even more powerful.

The largest work in the show, a photo collage by Mah, David Nester, and Areaux, induces flashbacks. Stuffed behind the edges of a mirror, dozens of copies of postcards and snapshots reveal how dramatically “what turns us on” has changed over the years. From the 1950s, you’ll find ducktails, lots of Vitalis, and beach balls decorously covering the private parts of women with hourglass figures. There’s the “Mod” look of the ’60s, replete with white patent leather, bellbottoms, hot pants, and Cleopatra masks (or pastel eye makeup and frosted lipstick). And you’ll find some of the classics, including the centerfold of a nude Burt Reynolds on a bearskin rug that appeared in the April 1972 issue of Cosmopolitan.

Adam Shaw takes us all the way back to classical Greece. In Veiled (oil on canvas), he sculpts the human torso with thick strokes of paint. Folds of drapery cover the figure’s face. Dark shadows along the edges of the pubis suggest the genitalia of both sexes in a beautifully executed work that resembles Greek sculpture and pays homage to the complexity of desire.

No exhibition of erotica would be complete without a ribald raunchy-and-red work of art. Doug Northern’s Tracing May — Tongue Painting (acrylic on masonite) shows a couple making love on a palpitatingly red mattress. The woman’s right foot stretches over the edge of the mattress and almost touches an electrical outlet. Her partner’s long purple tongue almost touches her breast. This electric-red and neon-purple painting counterpoints the exhibitions’s more reflective works and raises the temperature to torrid.

Many of the works express the fleeting quality of life and embrace the attitude of carpe diem. The lights of Val Russell’s ancient marquee still flashing around the barely-discernable letters “PUSSY” advocate sexual pride no matter how dilapidated the packaging. Bill Rowe’s red-and-yellow neon sign Don’t Stop hangs beneath an open-mouthed, eroded stone face that once gushed water in some outdoor fountain. Rowe’s installation exhorts us to burn our candles (or neon signs) at both ends. And his corroded fountain head, like the shattered stone visage in Shelley’s Ozymandias (“Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”), reminds us that everything slows down, stops, decays — except, perhaps, for an endless succession of disintegrating and regenerating worlds. Ahhh … sexuality.