This isn’t another story about Isaac Hayes. Or Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, and Booker T. & the MGs. While their voices and faces sold millions of Stax records during the company’s heyday, dozens of lesser-known musicians contributed their talents to the little label that did. Stax drew from Memphis’ deep reservoirs of talent — from its beginning in a garage on Orchi Road in the late 1950s to its bitter forced bankruptcy in 1975 — for its featured artists and for its supporting cast. Most of the studio musicians Stax employed for recording sessions lived in the city, and many have stayed. Memphis must have more residents who’ve played on Top 10 records than any city outside New York, L.A., and Nashville.

In honor of Stax’s 50th anniversary, we’ve dug up a few hidden treasures. The recognition these artists have received falls well short of the significance of their contributions to the Memphis sound. They have witnessed and participated in pivotal moments in Stax history and now share their stories.

In the beginning … a fan club and a pompadour

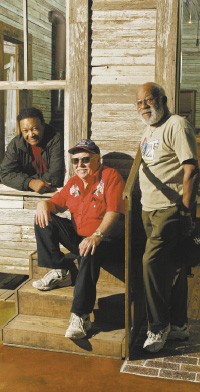

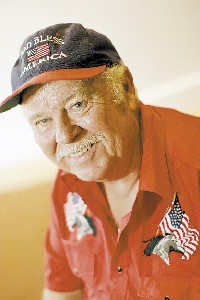

Charles Heinz goes back to the garage-studio beginnings of what was then Satellite Records. He recorded four sides for the label that would be Stax — including the local hit “Destiny” — in 1959, a time in the label’s evolution that predates its foray into rhythm and blues (the soul genre as such didn’t yet exist, either) and is, subsequently, overlooked in Stax history. It’s hard to find any mention of Heinz, a lifelong Memphian, beyond the wall of records in the Stax Museum, and his tracks were not included in the “complete” Stax singles box set released in 1991 or the Stax 50th-anniversary double disc released this year.

The artists whose records Satellite released before Heinz are dead or unaccounted for.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Heinz had a fan club and a pompadour back then. He sang in nightclubs with the Bill Black Combo and other bands. After his brief stint as a local pop star, he devoted his career to church music. He retired as music director of Central Church and helped found Redeemer Evangelical, where he conducts the choir and orchestra today. Here is his story in his own words:

“My influences were Mahalia Jackson and Mario Lanza. He was a tenor for the Metropolitan Opera. I would study things that they’d sing at the Metropolitan and then go out and sing rock on the weekends. It was an interesting combination. The soul that Mahalia Jackson put into songs connected with the instruction of how to sing correctly. It’s like a baseball player. Fundamentally, he’s got to know how to hit, but he’ll use his own style.

“I went to White Station and was singing with a group there that included Jim Dickinson on piano. I was introduced to the people at Stax, Satellite at that time, and they wanted me to record. In about ’59, Jim Stewart was looking for artists. Chips Moman and I wrote ‘Destiny.’ It was on the charts here in Memphis for about 10 weeks.

“We recorded at Pepper [also known as Pepper Tanner studio, formerly located at 2076 Union Avenue]. Stewart rented that studio to record, and they later did some overdubbing on McLemore. Bill Black played bass — I really enjoyed him.

“At that time, Satellite was not going in a rhythm-and-blues direction. With Carla and Rufus [Thomas] coming on, that changed things quickly. [Satellite] was going in a pop direction, but when they bought the studio on McLemore, it brought a lot of African-American people in [from the surrounding neighborhood], and they went in a rhythm-and-blues direction.”

The other Jerry Lee

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Jerry Lee ‘Smoochy’ Smith

Ask fans of early rock-and-roll to name their favorite piano-thumping Jerry Lee, and they’re guaranteed to say Lewis. But another ivory-tickler named Jerry Lee from Memphis has made his own mark on American music: Jerry Lee “Smoochy” Smith. Like his better-known namesake, Smith began his music career in the studios of Sun Records, where Smith played on recording sessions from 1957 to 1959. Smith wrote a riff that launched Satellite’s first million-seller and helped the company make a name for itself. Literally.

“I was playing in a band, and my guitar player was Chips Moman. Chips was the engineer at Satellite. We were playing one night at the Hi-Hat Club. In one of the songs, I throwed in a little groovy piano sound. Chips, having the ear for music he has, turned around and said, ‘Where did you get that?’ I said, ‘I made it up. It’s a rhythm-and-blues-type riff.’ He said, ‘Come on by the studio, and let’s put that down.’

“Chips called me one night and said, ‘I’ve got a group over here [at the McLemore Avenue studio], and we’re working on that riff you put out.’ He had added the horns in there. They were blowing two notes against my rhythm pattern. I said that sounds pretty good. I forgot about the song for a while. It stayed on the shelf maybe six months.

“Meanwhile, Jim Stewart had gotten in touch with Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records. Wexler came down to listen to some of the songs that had been recorded to see if he liked any of them. Chips played every song that they did. Wexler told him he didn’t hear anything that knocked him out. He was fixin’ to leave, and Chips said, ‘I’ve got one more song. This is an instrumental.’ He played it, and Mr. Wexler said, ‘Now that’s what I’m looking for. Only thing, I’d like for you to put a saxophone ride in it.’

“Chips called a session, and we went and recorded it. He added two horns, Gilbert Caple and Floyd Newman. Gilbert played the saxophone ride. Floyd, he’s the one that said, ‘Awww, last night.’ He came up with that.

“I wasn’t but 21 years old when we recorded that. It took us four weeks to get it where we wanted it to be. I played organ and piano on it. I didn’t have much faith in the song. It started climbing the charts. We went on the road, and finally it hit #1. It turned out to be a great song. We recorded it in 1961, and I’m still drawing royalties on it.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Howard Grimes

“The song has been put in movies, and a lot of different people have recorded it. One year, the NBA used it as their theme song. Every now and then something happens with that song, and I’m making more money off of that song than I did when it first came out. It has kept me going over the years.”

Smith’s song, “Last Night,” recorded by the Mar-Keys, was the first million-seller for Satellite Records. It came to the attention of a California record company, also named Satellite Records. The California Satellite offered Jim Stewart the name outright for a hefty fee. Rather than pay or risk legal action from the California company, Stewart opted to rename his company. By combining the first two letters of Stewart’s last name with the first two letters of his sister Estelle Axton’s married name (she had bought into the company a couple of years earlier), a new brand was born: Stax.

“That was my shot, and I missed it.”

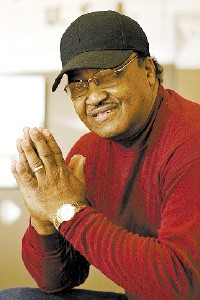

The lazy, laid-back beat that drove Al Green to the top of the charts in the late 1960s and early ’70s is one of the distinctive elements of the Memphis sound. Hi Records producer Willie Mitchell cultivated that groove at his Royal studio located one mile from Stax’s McLemore Avenue site. A different drummer, though, would have turned out different tunes. Name a hit from the Hi Records heyday and chances are Howard Grimes played drums on it. Though he made his mark at Hi, he got his start at Stax as a child prodigy.

Grimes lives a block away from the Stax Museum, yet, he says, he’s never been asked to participate in events there. “They don’t acknowledge me,” he says. “I don’t let it bother me, though I used to.

“I was self-taught on the drums. My mother had them big old 78 records of Big Joe Turner and Ray Charles. I’d play on the pots and pans. My granddaddy used to listen to the Grand Ole Opry. I’d sit and listen to it with him.

“I could hear the drums from the school over there on Smith Street where I lived in North Memphis. I came to Manassas in ninth grade. That’s when I took an interest in band — Mr. Able was the band teacher there. Mr. Able and them were into jazz, listening to Max Roach, Art Blakey, and these drummers. They started tuning me in.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Charles Heinz

“Mr. Able singled me out as a drummer that he felt would be successful. He used to let me out of school — I got an opportunity to record up there at Satellite. Rufus Thomas decided to cut a record one day, and it was suggested that I play on it. I was excited ’cause I had never recorded before and didn’t know whether I could do it. I was 12.

“I went up there and met Ms. Axton and Mr. Stewart. Chips Moman was the engineer. He was the most kindhearted man I’d ever met. He believed in me for some reason. It was Bob Talley’s band: Alfred Rudd, Wilbur Steinburg, Talley — he was a piano player but played trumpet on that session — Booker T. Jones, long before he became the MGs … Me and Booker were the youngest ones up there. The record was called ‘Cause I Love You.’ [Released in 1960 between Charles Heinz’ only two singles.]

“After that, they brought me back, and I cut Carla Thomas’ ‘Gee Whiz.’ [Released in late 1960, it was Satellite’s first national hit.] Something went wrong with the machine, so we did the session at Hi [Willie Mitchell’s studio at 1320 Lauderdale]. Marvell Thomas played piano, I played drums, and they had the Memphis Symphony, Noel Gilbert and his two kids. Sam Jones and the Veltones were the back-up singers.

“They called me back for William Bell. I also cut with Wendy Rene, Prince Conley. And I did a lot of instrumentals with the Mar-Keys. I never got any royalties. I got statements but never any money.

“A lot of [rumors] have come out over the years. Someone said that Al Jackson [Jr.] tutored me. Al Jackson never tutored me — I was before Al Jackson.

“[Stax] gave Booker T. an opportunity to record one day. I don’t know where I was, usually I was at home, but that day I left home. When I got back, my mother told me [Stax] had called. I was the staff drummer, but I called them back, and they said they had got someone else. I found out it was Al Jackson. Steve Cropper had recommended him. He called [Jackson] in that day for ‘Green Onions,’ and the rest is history. That was my shot, and I missed it.”

The man who kicked Isaac Hayes out ofthe high school band

High school bandleaders have had an influence on Memphis music that is huge and overlooked. To name just two, the great jazz orchestra leader Jimmie Lunceford taught at Manassas in the 1920s, and Harry Winfield tutored future Stax luminaries at Porter Junior High.

Emerson Able started teaching music at Manassas in 1956 and instructed many, including Grimes, who became prominent musicians. The most famous of his former pupils is the one who got away.

While a student at Manassas, Isaac Hayes couldn’t decide between Able’s band class or voice class. “I told him, ‘Go on,'” recalls Able. Hayes didn’t hold it against Able and later hired his old teacher to join the Isaac Hayes Movement. “Hayes introduced me on stage as the man who kicked him out of the school band,” Able says.

“I was not one of the musicians that hung around Stax. I had a job. They had been doing a lot of ‘head’ tunes at Stax [i.e., a song played from memory or verbal instruction rather than sheet music], and that can be very time consuming. A head tune is like ‘Last Night,’ a simple tune that they can pick up on. Basically, that was the Stax sound.

“Musicians didn’t always get credit for what they had recorded at Stax. They were doing what they called demos. You’d go down, record a demo, and they’d pay you 12 bucks. They have you to believe that it was only a demo, and they’d have you back to cut it [i.e., record for the purpose of releasing the material rather than practicing on a demo]. Then they’d [release] it and have you believe you’re not on there. Some of us could identify our errors, and we knew it was us.

“Another game they’d run, they’d make a demo, then play it on WLOK for a while. If [African Americans] in Memphis like a record, we’ll like it anywhere. So they’d test it on black listeners here, and if it got a lot of requests, they’d make a record out of it.

“Onzie Horne [Hayes’ arranger] brought me into Hayes’ band. That’s when we hit the road. We had charts, he had accomplished musicians, and we never would have gotten through all of that shit had it been a ‘head’ thing.

“We lost the music [traveling] between San Francisco and Los Angeles for Wattstax. We didn’t know it was missing until it got there. We assumed the airlines lost it. We had to write the music from memory before Wattstax.

“The other thing that happened, the tune we originally did for Wattstax was a Burt Bacharach tune [probably “Walk On By”]. After we recorded it at the Coliseum in L.A. and got back to Memphis, we had to go back out there. Bacharach would not give permission to use the tune [in the Wattstax film]. They fixed up the Coliseum, and we shot again.

“We’re supposed to be getting monies off of that, but we ain’t getting shit.”