Most Tuesday nights, when the weather’s right, you can find Memphis’ b-boys hanging out on the Highland Strip. Break dancers, graffiti writers, and hip-hop aficionados congregate outside Whatever, at the corner of Highland and Southern, their tools of the trade (backpacks, sketchbooks, and a boom box) piled on the sidewalk beside them. A monolithic mural bearing the b-boys’ group tag, UH, looms overhead, while beneath their feet, a linoleum square provides the perfect dance surface.

Ask anyone here what the acronym UH stands for, and each person will give you a different answer: Urban Hieroglyphics, Unsung Heroes, and Underground Hip-Hop all garner mentions, along with Under Hypnosis and Unholy Harvest.

Even if you haven’t attended the weekly — albeit unofficial — b-boy convention, you’ve probably noticed the UH tag. It’s all over town, covering walls outside accommodating businesses like Whatever and inside Midtown’s Umai Restaurant. Chances are, you’ve noticed illegal UH tags as well, rushed paintings that blot the scenery on the busy I-40 corridor and in certain inner-city locations.

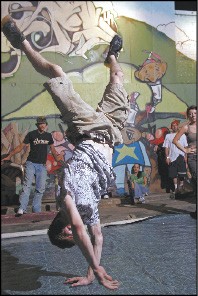

On this balmy evening, James Brown’s “Soul Brother #1” blasts from the speakers as two guys rifle through each other’s notebooks, a break dancer in black T-shirt and shorts nodding appreciatively over their shoulders. Sirens wail as a pair of fire trucks roar up Highland, but more and more people hear the music and come to the party. “That dude’s cold,” one passerby admiringly notes of a dancer who pirouettes on his toes, his knees, and elbows before gracefully slipping into a gravity-defying headspin.

And then the dancer — he’s called Nosy T — leaps back to his feet, shaking off the applause and making room for another b-boy to move into the spotlight. Nosy’s technique is effortless, gracious, jubilant, as he bends his skinny frame into impossible shapes, then steps off the mat to wait his next turn. James Brown has given way to a remix of Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billy Joe,” and a train rumbles noisily down a nearby track, but until the linoleum’s rolled up and put away, kids will keep joining the throng.

Nosy can’t remember a time in his life when he didn’t know about the b-boy scene. “I’ve always liked hip-hop,” the 19-year-old proclaims, “and I met up with older kids who got me into the scene and helped me develop my skills.” His backpack full of spray paint is, he claims, his security blanket, but since his 18th birthday, he’s been busted for illegal tags twice.

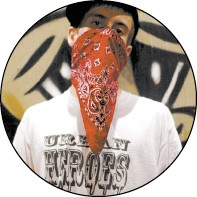

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Nosy T and the UH crew

“You have to be creative,” Nosy says of graffiti writing in Memphis. “Everything’s so flat that the scenery’s pretty limited. You have to find new ways to put your name out there. It’s common for a lot of people around Memphis to just scribble on things. I’d rather spend a lot of time on a nice production — a legal wall somewhere — but nine out of 10 people say, ‘We don’t want it.’

“This is artistic expression,” he insists. “It’s more than tag bangin’, but if you want to look at my stuff and say it’s vandalism, I can’t change you.”

Even so, Nosy and the rest of the UH crew, which includes writers like Foe, Betor, Epok, Cinko, Els, and Wase, have managed to win over several Memphis business owners.

“The kids came in and asked for permission,” Bill Holt, co-owner of Holt Tire Service on South Mendenhall, says of the UH mural that stretches across the back of his shop. “They were very straightforward, very open. We told the guys, ‘We realize there is such a thing as wall art, but we’re not into gang graffiti at all.’ It turned out that these kids have some talent.

“I have taken some grief for it,” admits Holt, an unlikely graffiti supporter. “It’s from non-customers, people I’ve never seen before who are scared to death that it might invite gangs into our neighborhood.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

In mid-April, Nosy was arrested while putting the finishing touches on Holt’s store. “I was painting when the cops came up, and the next thing I knew, I saw three of my friends with their hands on the car waiting to be frisked,” he recalls. “I walked down, and a police officer put his hand on the back of my neck and slammed me down on the hood. Cinko got the owner, and when the cops found out we had it legal, they let us out of the car. I asked for a badge number, and the cop looked at me and said, ‘What do you need — a play-by-play?’

“I laughed at first, but the more I thought about it, the more it pissed me off. I said, ‘You guys aren’t doing any good — you’re just out here harassing us and wasting our tax money.’ A cop said to me, ‘You don’t work or pay taxes.’ I flipped out, asking, ‘How could you assume that?’ I ended up in a holding cell at 201 for eight hours. I went to court the following Monday, and the judge threw it out.

“Here I am, trying to pursue my art form in a legal way, and I get thrown against a cop car and put in jail,” Nosy muses. “If we were out there painting a sunset and flowers, it would be all good, but because we’re graffiti writers, we’re looked at as vandals.”

“There’s such negative connotations with graffiti,” says 21-year-old Gnars, a co-founder of UH who’s currently enrolled at the University of Memphis. “There are people behind the work, and a lot of people who write have stuff going for them. A crew is not a gang. It’s about sharing a universal idea and working with people because you paint for the same reason.”

That thinking, he says, is also why he left UH two years ago. “We’re all still friends. I’m not any better than they are, but they’re more bombers [illegal graffitists]. I bombed hard when I was a kid, but I don’t feel the need to do that anymore. I’m not into the legal thing, either. I want to go out and take my time painting big productions on track sides or abandoned buildings and let somebody find it.”

“I prefer to do legal walls,” says 16-year-old Wase, the youngest member of UH. “It’s an art form for me. It’s not about destroying everything. When we find a wall we really want to paint, we show the owner a picture to give them an idea of what we can do and just hope they say yes.

“You can knock out a piece in one day, but sometimes, I don’t feel like rushing,” Wase says. “A lot goes into it. You can freestyle it or sketch it out. For the background, you’ll use rollers, then spray paint for all the piecing. I like Krylon — it’s cheap, it’s accessible, and it’s thick.”

Comparing Wase’s eloquent writing style with the hastily scrawled gang graffiti that also mars the Memphis landscape is like putting a kindergartner’s portrait next to the Mona Lisa. Yet many civic groups, such as the Cooper-Young Community Association, frown on graffiti in all its forms. The neighborhood is rife with easy targets, such as the train trestle and the alleys behind the area’s many restaurants. Another point of contention — a legal wall offered to local graffitists by Sharon Andrini, who owns a business on Young — has some people seeing red.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Some illegal tags, like the graffiti on the Sears Crosstown building, are created by visiting graffitists who find Memphis’ unblemished surfaces irresistible. “UH is really the first big wave of writers to hit Memphis,” Nosy says, “and since it’s new, not everyone understands the concept of having more than one person out there. Too many people are making assumptions.”

Elizabeth Alley, the UrbanArt Commission’s director of public art, says most people don’t really know the difference between gang graffiti and graffiti art: “We see both as the same thing — maybe a little threatening and definitely an encroachment on private property. Maybe what this UH collective should do is show us what the difference is.”

Memphis Police Department detective Monique Martin already understands the distinction. “With murals, the [artists] are usually given permission to paint, and we see most of these as positive messages,” Martin says. “If someone wants to project that image within their community, we can’t stop it. Any graffiti is vandalism, [but] we’re most concerned about gang graffiti, things like bridges that are tagged and other territorial markers.”

In Louisville, Kentucky, civic leaders tried to legitimize graffiti art by offering a legal graffiti wall in the East Market Arts District, the city’s equivalent to Memphis’ South Main, in October 2006. “One of the things you want good art to do is stir conversation, and we felt like this would do that,” says Cynthia Knapek, a member of the the Mayor’s Committee for Public Art in Louisville.

But six months later, the project was kaput.

“There were definitely two distinct groups of people,” Knapek confirms. “True artists who happened to use aerosol as their medium and a whole separate group of folks who just wanted to have fun with a can of spray paint.

“This particular phase of the project is over,” she says, “although we may try to do something similar in the future.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Foe and Betor in Orange Mound

One Sunday, the UH crew decides to work on a legal wall in Orange Mound. As Cinko puts it, “We go paint [there] because those guys are a lot cooler than anyone else.” By early afternoon, Betor and Foe have pried open a bucket of Glidden Black Satin and begun rolling the paint over a cinderblock wall. They’re creating a blank canvas — and covering an intricate design painted by Wase just hours earlier.

As they work, they talk.

“Graffiti’s my main thing,” says Foe, who also MCs and DJs with local hip-hop groups. Now 25, he’s been graffiti writing since 1990. “Our crew is like a family,” he says, explaining that he views today’s work as a gentle form of hazing.

After breaking out his arsenal of spray cans, Betor, a 20-year-old artist who works in multiple media, delves into local graffiti history. “Memphis has had some of the most amazing writers from the South,” he says. “A crew called TM inspired me, and when they left, UH picked up the slack. When I started, I was a teenager, just tagging and leaving markers. Now, it’s almost an addiction.

“If anything, our crew is about sticking to the elements of hip-hop,” he adds, echoing comments made by the graffitists depicted in the movie Wild Style, which documents the New York b-boy scene of the early 1980s.

“This is just chill, trying to do something nice,” Foe murmurs, stepping back to analyze the gold and blue forms taking shape.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Nosy T at Whatever

Hours later, he and Betor sit on a concrete wall across the street, idly contemplating the empty paint cans that, for the time being, lie scattered across the parking lot.

Foe offers a language lesson. “A ‘burner,'” he says, “has every color in it. A ‘piece’ is a masterpiece. ‘Bombing’ is doing fast illegal work.”

Betor displays the variety of interchangeable caps — used to create myriad effects — jumbled in the bottom of his backpack and points out the difference between a needle cap and a calligraphy cap.

“We weren’t even trying to get this wall,” he says softly of the day’s work, which sparkles in the fading sunlight. “We were doing a nearby building, and the owner said, ‘If you want, you can do this one too.'” Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Betor sketch

For weeks, the UH crew has been scrambling for legal walls in preparation for the second annual Soul Food graffiti jam, slated to take place June 15th and 16th.

“Last year’s Soul Food jam was fun, almost like a carnival,” declares Whatever proprietress Mary Setser, who employs b-boys like Nosy, hip-hop DJ Redeye Jedi, and Tunnel Clones MC Bosco at her retail shop. “At one point, the police came by and said, ‘Ma’am, do you realize that people are painting graffiti on your building? Don’t you want it stopped? They’re stopping traffic. It’s a hazard!'”

Setser laughs. “I told them, ‘I’m sorry, but that’s your problem.’ Since then, I’ve had people come in and ask who did the painting, so they could hire them to decorate their businesses. Someone from the city came in and asked about submitting drawings of the work to see if they could get permission for UH to paint expressway walls and other places around town. They’re gonna get graffitied up anyways. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have something nice up there?”

While the expressway offer has yet to materialize, Nosy has secured a legal wall at the University of Memphis for Soul Food 2. Through his former art professor, Cedar Lorca Nordbye, he’s gotten permission to paint the construction wall surrounding the school’s new University Center — and $2,000 to pay for paint.

“We’ve got 15 Memphis writers. Everyone else is coming from out of town. We’re going to have a PA system blasting old soul music while we work,” he says.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Betor on Jackson Avenue

DJ Redeye Jedi plans to offer scratching lessons at the event, which will lay the groundwork for the Memphis Hip-Hop Academy that he, Nosy, and other local b-boys hope to launch this fall.

Nosy’s excited, even after he remembers that the U of M wall is already slated for demolition. “Betor and I talk about that a lot,” he confides. “Most of our work we like best isn’t about the actual pieces, which we have photographs of anyways. In the long run, I think, it’s more about the act of going out and doing it.”

In early May, Wase quits UH.

“We all have our own ideals about where we want to take our graffiti, and right now, I don’t feel the need to be in a crew,” he says.

Wase doesn’t find fault with Foe or Betor for covering his Orange Mound tag, although he does say, “I don’t think it had anything to do with hazing. They just needed somewhere to paint. I’ve gone over their pieces before too.”

Turning a critical eye to the rampant graffiti work in Memphis that grows, like kudzu, overnight, Wase says, “It’s getting out of hand. Everything around the legal walls is getting tagged. When you tell people to be respectful [of business owners], they do it anyways. That area around Southern and Highland looks like complete shit.”

One sunny day, without much fanfare, a squad car rolls into a parking lot off Highland to handcuff a graffiti writer. Around the corner, Foe and Betor work, unruffled, as the kid gets busted for tagging an illegal wall that’s already coated with paint.

Even though Wase has dropped out of UH, he’s hardly quit painting bold productions all over town. “I’ll still paint with them, and they’ll still be my friends,” he says of his former cohorts. “I’m just not so into the hip-hop culture. I like it, but I don’t involve myself in every aspect of it or spend every minute of every day thinking about it.”

For Nosy, however, UH is Memphis and Memphis is UH: “We grew up here, and we love Memphis. We love everything about Memphis, but it goes deeper — we’re family.

“This crew is about collaboration, and some people aren’t about that at this point in their graffiti career. It’s fine, and it doesn’t make me respect them any less. When I paint, it’s only with crew, but if Wase or Gnars call me, I’ll work with them too,” Nosy says. “I love ’em as much as anyone else.”

One Friday in mid-May, Foe offers to take me to an illegal graffiti site currently used by the UH crew. We drive east on I-40, then park at a box store and walk a quarter-mile down the highway. I follow Foe as he disappears over a guardrail. The drop is treacherous, but he descends with the agility of a mountain goat, then patiently waits for me to catch up.

We trek single-file through a wooded area, pausing at a wrecked car that sits in a shady glen, saplings growing through the engine block. The vehicle has a few graffiti tags on its burned frame, but Foe continues on to a highway overpass that crosses the Wolf River. Here, the trail ends, and we duck into a space the size of a football field that’s completely shrouded by trees.

Inside, it’s 10 degrees cooler, and the sound of cars whizzing over our heads gives way to a hushed silence. A makeshift shelter, constructed of faded sheets and broken branches, sits like Huck Finn’s raft between two concrete pilings.

On the far wall, I spot some old tags — names like Billy Bob and Cyclops and some racial slurs. But a series of UH pieces, along with adjoining work from Gnars and Wase, nearly obliterates the earlier scrawls. Each “canvas” is approximately 10 feet high and 20 feet wide, demonstrating the precision and creativity of unhurried artists.

This far from b-boy civilization, the effect of the art is startling.

“It’s like a cathedral, almost,” Betor says later. His respect for the place is evident. Not a single piece of trash lies on the sandy ground, a sharp juxtaposition to the litter-clogged roadway overhead.

“It’s a place to paint and chill out,” Foe says. “It’s a calm spot, where we can take the time to step back and look at our work, figure out what we’re doing, and get our techniques down.”

The luxury of such a secluded site isn’t lost on me. I blink, trying to take in the beauty of the scene as Foe trots past, heading to the river itself. Leaping down a steep, short incline, he points to another wall, which spans the water. On it, he has spelled his name in bold red-and-white. The piece, which stretches across hundreds of feet of concrete, took Foe two days to paint, while he stood in knee-deep water. Yet, I wonder, who will see it but us?

“As far as adrenaline goes, you can’t beat a good tag,” Foe says. “Most of it is just taking a chance and hoping no one sees you,” he says. “But it’s so much more satisfying when you have time to get the piece done.”

For a longer version of this story and more photographs, visit MemphisFlyer.com

June 7th.