From rockabilly and Philip Glass to diamond mines in Africa, this year’s exhibitions ran the gamut of culture, art, and current events, and some of the most evocative artworks were created by already accomplished artists moving in new directions.

For “Perspectives,” the Brooks Museum’s juried exhibition this summer of regional artists, abstract painter Bo Rodda filled an entire wall with a computer-generated world, one with laws of physics different from our own. There were no horizon lines, no solid ground in this alternate universe. Instead, swerving lines, printed on metallic paper in endless shades of gray, read like infinitely complex galvanized interstates careening simultaneously toward and away from the viewer.

Warren Greene, an artist best known for saturate pigments oozing down large canvases, also went beyond color and form to infinite shades of gray in three of his strongest works in “Paleoscapes” at Perry Nicole Fine Art in December. Like a Phillip Glass symphony, the subtle rapid shifts in tone in “Searching for P. Glass” generated unexpected images as what looked like trails of electrons, interference patterns, jet streams, ectoplasm, and snippets of dreams slid our point of view across surfaces sanded as smooth as glass.

David Comstock’s exhibition “Flow” took black-and-white abstractions to new levels of raw power at L Ross Gallery in March. Rods pierced egg-like shapes on frayed and torn canvases in what looked like moments of procreation and checkmate in the well-worn board game of life.

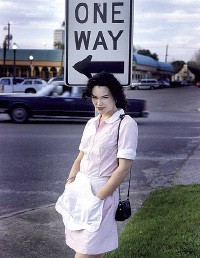

Jonathan Postal’s Waitress, Roadside, TX

Also in March, in an otherwise empty David Lusk Gallery, Terri Jones drew delicate, nearly invisible lines on the wall and on large sheets of vellum that were bathed in the sunlight pouring through plate-glass windows. Those of us who stayed awhile in Jones’ spare luminous space experienced something akin to Buddhism’s Sky Mind.

Bob Riseling’s “Halcyon Days” premiered Memphis College of Art’s new gallery On the Street in November. Pale colors, deep shadows, and haunting monolithic shapes paid homage to the dead trees standing sentinel on Horn Island’s post-Katrina beaches, an ancient hulk of a barge stranded on one of its sandbars, and countless pieces of driftwood washed up on its shores.

Highlights of the year also included Hamlet Dobbins’ luminous textural abstractions at David Lusk in October and John McIntire’s summer show at Perry Nicole that transformed smooth, cool stone into sexual icons, fertility fetishes, and sacrificial gods. And at L Ross Gallery in November, in some of the best works of his career, Anton Weiss scattered scratched and gouged scraps of metal across large earth-toned paintings accented with thalo blue, scarlet, and cadmium yellow.

Last year’s most riveting works of art confronted brutality and oppression. Memphis College of Art’s March exhibition, “Reasons To Riot,” included Zoe Charlton’s searing mixed-media drawing Destiny, in which a man leaned back on his haunches. His face and upper body were whited-out, and the prow of a 17th-century slave ship was strapped around his waist like a dildo. Humanity’s unexpressed (repressed, denied, watered-down) passions were crammed into his phallus, which was as pointed as this artist’s insights, as unadorned as truth, as double-edged as our species’ capacity for cruelty and joy.

A work from David Comstock’s exhibition at L. Ross, ‘Flow’

In early fall, Clough-Hanson Gallery showcased 15 works from Eliot Perry’s collection of contemporary works by African artists, many of them internationally acclaimed. Among them was Wangechi Mutu’s sinuous, cinematic, horrific collage Buck Nose. The images depicted an antelope shot with a high-powered rifle, blood exploding around its head and horns and entrails coiling around a starving girl curled in a fetal position. Most chillingly there’s a manicured hand caressing a gemstone, reminding us that in today’s global market, African diamonds are prized, but life is still cheap.

In “Two Years,” Jay Etkin Gallery’s December show, we saw Sandra Deacon Robinson’s paintings evolve from Klimt-like mosaics of glittering gemstones to abstractions of Louisiana wetlands. At the top of one of her most beautiful works, the 40-by-60-inch painting Protected, wisps of ochre almost brushed our foreheads, delicate tangles of lines at the bottom reached toward our torsos and legs, and muted golden light at top right suggested we were at the edge of a moist, dark cocoon with a clearing just ahead.

Also at Jay Etkin in December was photographer Jonathan Postal’s “On the Road.” In one of the show’s most disarming images, Waitress, Roadside, TX, a woman with jet-black hair dressed in a white apron and light-pink uniform stands at the side of a thoroughfare. Whether she waits tables in an upscale diner with a retro theme or is working in a smalltown café that looks pretty much like it did when it opened in the Fifties, this woman looks comfortable in her own skin. With a wry, sensual smile she leans back and sizes up Postal (and any gallery viewer who dared to look her in the face).

Postal is best-known for his black-and-white photographs of people living at the edge. While his images of burlesque queens scowling after a swig of hard liquor and wrestling fans howling for blood are fever-pitched and powerful, this body of work’s wide-open spaces and wry waitress boded well for a country at moral and political crossroads in need of citizens, whatever their lifestyles, who can step back and see things clearly.