Monday afternoon at FedExForum, in the middle of the fourth quarter of a previously ugly, physical game against the Chicago Bulls, the Memphis Grizzlies pulled away with a barrage of alley-oop dunks and three-point bombs — Stro Shows, La Bombas, Spanish connections, and Rudy Gay daggers. It was a fun, rousing conclusion to the team’s annual, nationally televised, Martin Luther King Jr. Day showcase, and coming at the exact midpoint of this NBA season, it capped off the first half on a highpoint.

Unfortunately, for the Grizzlies, highlights have been few and far between this season. Monday’s win brought the team’s record to 12-29, only two games better than the 10-31 record the team sported at the midway point a year ago in a season in which the team ended up with the worst record in the league. Along the way this season, the Grizzlies have won back-to-back games only once and have yet to notch a three-game win streak. This is not the performance most fans expected from a talented, albeit young, roster seemingly capable of making a 15-game-or-so improvement on last year’s 22-60 record.

Fans who haven’t been paying close attention (and, with average home attendance down more than 1,000 per game this season, that’s a growing group) could be forgiven for thinking that this year’s model is more of the same for the NBA team in town.

But, despite the disappointing similarity in the win-loss column, this Grizzlies team is playing better and, most importantly, more meaningful basketball than they were a year ago.

Last season, the Grizzlies closed the season with lineups filled with middling veterans (Chucky Atkins, Damon Stoudamire) and soon-to-be-departed journeymen (Dahntay Jones, Junior Harrington) playing for an interim coach (Tony Barone) and lame-duck executive (Jerry West). Despite the up-and-down development of rookie Rudy Gay, it was a team already waiting for the season to end soon after it began.

This season’s team isn’t waiting on the future, but building it, with each of the top eight players in the rotation under the age of 28 and potentially part of the long-term future and with a new, presumably long-term management team (coach Marc Iavaroni and general manager Chris Wallace) in charge.

On the floor, this younger, less experienced team has been more competitive, even if the difference in wins has so far been minimal. Last season, the Grizzlies finished with the worst point-differential in the league in addition to the worst record, the former statistic generally a truer measure of how good a team is. Their record reflected their quality of play.

At the mid-point of this season, the Grizzlies have the league’s fourth worst record but only the ninth worst point differential. The reason for this disparity is the most demoralizing aspect of the team’s season so far: This Grizzlies team has been unbelievably bad and/or unlucky at finishing off close games.

Through 41 games, the Grizzlies have gone an astounding 1-10 in games decided by three points or less or that go to overtime. Compare this record in close games to that of other “bad” teams this season: Of the five worst teams in the league aside from the Grizzlies, only one (the similarly disappointing Miami Heat at 2-7 in close ones) has played even five nail-biters.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

That the Grizzlies have played so many of these games is a testament to the team’s talent. Unlike Seattle (2-3 in close games) or Minnesota (1-3) or New York (1-3), the Grizzlies are good enough to compete. That the record in these games is so dismal is a comment on many things: A rookie head coach still feeling his way (success in tight games is often used as a barometer of quality coaching), youth, porous defense, a lack of clutch scorers. But the 1-10 record is so extreme that it’s also a bit of a fluke.

Aside from the losing record, the biggest disappointments this season have probably been the two high-profile big men the team acquired in the offseason — 6’8″ former player Iavaroni and free-agent seven-foot center Darko Milicic.

Milicic played reasonably well the first month of the season, averaging 11 points and 8 rebounds in November, but his game has been on the decline since, averaging a more Tsakalidis-like 5 points and 5 boards a game over the past two months.

A robotic offensive player with an over-reliance on his left-handed jump hook, Milicic’s game has suffered from a series of minor ailments (thumb, ankle, knee) and resulting shaky confidence, only compounding his struggles to make shots around the basket. Sadly, it’s become clear that this team needs a different kind of center to thrive — one more adept at providing energetic help defense and rebounding out of his area. It’s hard not to think that, had the team been able to acquire Cleveland’s Anderson Varejao in free-agency instead, they’d be at least five games better right now.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

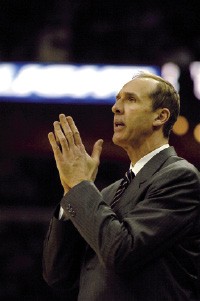

A long-time assistant under some of the league’s best coaches (Pat Riley in Miami, Mike D’Antoni in Phoenix), Iavaroni came into the job with a seemingly perfect pedigree, but also without any head-coaching experience at any level, and it’s shown. He’s taken longer than seemed necessary to find his way through the roster and settle on a rotation that most close watchers of the team would have selected from day one, along the way showing a legitimately odd commitment to ineffective free-agent swingman Casey Jacobsen.

On the sidelines, Iavaroni has seemed to rely on his assistants in game decisions much more than previous, veteran Griz coaches Hubie Brown or Mike Fratello, something that is neither surprising nor necessarily a bad thing, though it does speak to his own learning curve as a head man. Regardless of the approach, Iavaroni has certainly left himself open to more than usual second guessing of his late-game decisions en route to that 1-10 record in close games.

To Iavaroni’s credit, however, he’s generally kept his eye on the franchise’s long-term strategy rather than lapsing into the more common coach’s tendency to worry only about the game in front of him. His primary focus has been on implementing an uptempo style and developing the young players needed to make it work. And you can see this success in the promising seasons of the two players most likely to form the core of the Grizzlies’ future — 21-year-old second-year forward Rudy Gay and 20-year-old rookie point guard Mike Conley.

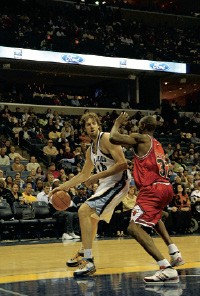

After a rocky rookie season, Gay has taken the kind of leap that suggests stardom: He’s emerged as a serious scoring threat, challenging Pau Gasol for the team lead and Portland’s Brandon Roy for top scoring average among second-year players. Along the way, Gay has proven both versatile and clutch: He’s the only player in the league in the Top 40 in both dunks and made three-pointers, and his late-game threes to beat the Spurs (over Duncan) and to go to overtime against the New Orleans Hornets are season highlights.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

Rookie Conley’s immersion was delayed by a combination of injury and coaching decision, but, since moving into the lineup at the beginning of January, he’s already proven to be a very effective lead guard. Even as a rookie who was still a teenager on draft night, Conley has created more shots with fewer turnovers than either Stoudamire or backup Kyle Lowry have. His two biggest adjustments — outside shooting and learning to finish plays over bigger, more athletic NBA defenders — have also, so far, proven less of a problem than expected.

If Conley’s production as a starter (10 points, 6 assists, and 1.3 steals per game on 44-percent shooting) doesn’t seem like much on the surface, put it in context — of his age (20), experience (one year of college ball), and position (point guard, the hardest in the league to play as a rookie) — and then remember how much Gay and Hakim Warrick struggled as rookies and how much better they got as second-year players. If Conley makes a similar improvement next season, the Grizzlies could have another young star on their hands.

And put both Gay and Conley in a wider league context: Among NBA players age 21 or younger, only the Lakers’ Andrew Bynum, 20, and Seattle’s Kevin Durant, 19, have matched Gay’s combination of production and potential. Among players who have yet to reaching drinking age, only the same pair have played better than Conley.

It’s been the overdue insertion of Conley into the starting lineup that might be turning this season around. Without Conley starting, the Grizzlies went 8-22 (a .267 winning percentage) with a -5.0 point differential. Since promoting Conley, the team has gone 4-7 (.364) with a (barely) positive point differential (+3 across 11 games). Could they play .500 ball in the second half? It’s possible.

But it isn’t just Conley that has the Grizzlies looking more like the team fans expected to see back in November. It took a while, too long perhaps, but the Grizzlies are finally putting their best lineups on the floor: Conley in; Stoudamire out. Crafty sharpshooter Juan Carlos Navarro getting consistent minutes and shots; ineffective Jacobsen on the bench. Younger, more talented Hakim Warrick playing over less reliable Stromile Swift. And then there’s Pau Gasol.

The team’s ostensible “franchise player,” Gasol got off to a slow start due to his own series of minor ailments and averaged a decent but sub-par 17 points and 7 rebounds on 49 percent shooting in November. This lackluster production enraged segments of the fan base and local media already prone to histrionics on the subject of Gasol, but it was clear to anyone who’s watched him over the years that he wasn’t right physically and clear to anyone with an active brain that Gasol wasn’t past his prime at age 27.

Gasol started to come around physically in December, his production ticking up to 18 points, 9 rebounds, and more than 3 assists per game. This month, fully healthy and with improved talent around him, he’s been better than ever, averaging 23 points, 11 rebounds, 3.5 assists, and 2 blocks per game while shooting 54 percent from the floor.

One of the great myths of Grizzlies basketball is that Gasol hasn’t improved since his unexpected rookie of the year campaign in the 2001-2002 season, when, in fact, his game has improved incrementally — aside from a few injury setbacks — every season: His shooting, his passing, his shot-blocking, his rebounding, his ability to handle the ball under pressure, even his still mediocre-at-best defense have all ticked up over time. Since rounding into shape physically, Gasol has played a little bit better than he did last season, which was a little bit better than the season before, and so on and so on.

That said, trading Gasol is still very much an option for this team, and should be a subject for further research as we get closer to the league’s late-February trade deadline. Gasol’s fate is something to watch in the second half, but the real story should be on the court.

Instead of a team waiting for a season to end, Grizzlies fans now get to watch a team busy being born, with all the messy growing pains that implies.

This season, more than ever, the Grizzlies have suffered in comparison to the other “pro” team in town, the currently top-ranked one operated by the University of Memphis, a franchise whose built-in advantages in a relatively non-competitive system will make them a better bet each and every year for fans only concerned with seeing the home team win.

The pleasures of pro ball are both more micro and macro than the college variety. In the pro game, there’s more to be found in the small details of games, in the simple pleasures of watching the world’s greatest athletes at work. And then there’s the big picture of watching how teams and individual players develop over the course of a long season or over many seasons. What chess moves made in the coming months — on and off the court — will set up larger successes (or continued failures) down the line?

Last spring, pro hoops fans at FedExForum only got to watch a team in a holding pattern — twiddling their thumbs waiting on the lottery. This spring, the basketball is more meaningful, and the hope — in the form, especially, of Gay and Conley — far more tangible than dreams of a lucky Ping-Pong ball.