In December 2007, Memphis artist David Hinske moved to Taos, New Mexico, opened a gallery in March, and a month later, took a 2,400-mile road trip. When Hinske returned home, he processed the previous six months by painting and putting together “Road Work,” the exhibition now on display at Jay Etkin Gallery.

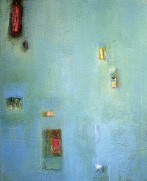

Many of Hinske’s beautifully modulated paintings are punctuated with small crevices and openings so scumbled, translucent, and free-form they seem to appear and disappear before our eyes. The blurred yellow squares and rectangles in the deep-blue acrylic-on-plywood 560 Rooms, 28 Miles bring to mind the lighted windows of the rows of motels Hinske drove past at dusk looking for a place to sleep.

In an interview, Hinske described pumping gas at midnight, dressing as casually as he wanted, and sleeping and eating whenever he chose. Freedom of the road is beautifully recalled in Red Shirt, No Shoes, a deep-red acrylic-on-canvas dotted with green fields and darkened windows of mostly vacant motels in small New Mexican towns like Tecumcari. On the right side of the painting, a stroke of pale pink slices the crimson background, underscoring the range of Hinske’s feelings, vibrating the entire chord of red.

Forty washes of white acrylic tinged with yellow simulate linen sheets in Sleep in Your Own Bed. Delicate cross-hatched portals open from the inside out as impressions of the past six months float into consciousness and are assimilated. The artist’s mind clears, and while driving across endless expanses of Texas, an eye-popping, purple-red sliver floating in yellow in Amarillo strikes Hinske’s retina (and ours) with the force of revelation.

Through September 22nd at Jay Etkin Gallery

In Jean Flint’s exhibition “Surface Attraction” at On the Street Gallery, energy arcs across time and space, explodes from the wall, and snaps objects like toothpicks in its wake. We can feel the energy building low to the ground in the eight-foot-square metal quilt Ring Cloth. Circles of baling wire at the center of the metal fabric lean toward one another as they are lifted several inches from the floor by a nearly invisible wire attached to the ceiling.

Jean Flint’s Surface Location

Large tornado-shaped cones fashioned out of 19th-century mailbags balance on top of early-20th-century topographical maps in Surface Location and create a sense of energy and information spiraling across expanses of time and space. Under the gallery lights, Couch Springs (37 of them) cast shadows and the distinct impression that the springs are coiling and recoiling across an entire wall.

Flint suggests the aftermath of destructive force in the mixed-media work Attraction. Multiple lines of slender string pinned high on the wall arc like cables of a suspension bridge. Some of the strings attach to sandbags piled on the floor. Others lie loose and serve as haunting reminder: For all our attempts to shore up levees and bridge large bodies of water, when water and wind combine, bridges can snap and lives can unravel like thread.

Through September 20th at

On the Street Gallery

David Hinske’s 560 Rooms, 28 Miles

The centerpiece of “Transformations,” April Wright’s exhibition at Artists on Central, is a nearly 800-pound, five-foot-tall ceramic sculpture Let Me Live Again, which looks like an ancient tomb and a huge, hollowed-out human torso. Every square inch, inside and out, is molded into fungi, coral, roots, tentacles, or the claws and incisors of predators — an entire evolutionary phyla that suggests the persistence of life.

Wright’s visionary works fill the gallery to near-capacity. A ceramic slab of the Mississippi River, Let the River Flow, evokes the heft and weight of a fast-moving current oozing deep into a riverbed, carving silt/sand/stone into oxbow lakes, sand bars, and canyons.

The large mural Let the Balance Begin consists of seven concentric circles — symbols for God, the sun, and a womb. Instead of precious stones or monumental slabs of granite, like those found at Stonehenge, Wright creates her circles out of fist-sized chunks of clay that look like Precambrian trilobites, Idaho potatoes, or dried dung. This complex work evokes Eastern and Western worldviews and some of the Bible’s most poignant passages: As above, so below the least of these God in all things.

Three of the show’s smallest, most evocative works a triad of anemones — titled Let Me Hide No More — suggest the creative process of all artists, particularly that of sculptors.

These sea-creature tentacles could be Wright’s long, expressive fingers, poised, slightly bent, reaching in all directions, waiting for the next creative impulse before she sinks her hands back into the clay.

Through September 30th at Artists on Central