On the evening of the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center’s 36th annual Living the Legacy of Nonviolence, Tami Sawyer accepted the Happy Jones Award on behalf of #TakeEmDown901. As the masses of people stood and applauded, Sawyer said, “Everyone in here … was a part of #TakeEmDown901. The reason it was so successful as a movement is because it was a people-centered movement. It gathered the voices and sentiment of our entire community.”

Sawyer’s words were a reminder of the power of widespread participation in collective political action. When members of the community are in conversation and they collaborate and strategize together, social change is more impactful and long-lasting. #TakeEmDown901 demonstrated how community dialogue with differing opinions on how to address local issues helps complicate and strengthen resistance to not only racial inequality but also symbols of racial violence.

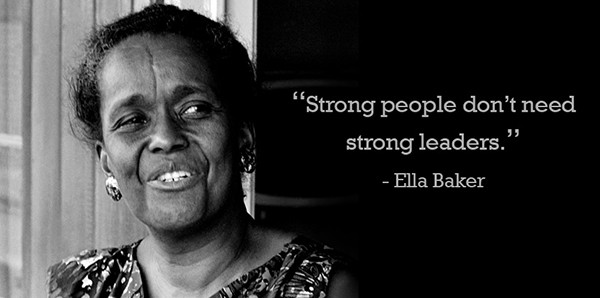

The approach of a people-centered movement is reminiscent of Ella Baker’s grassroots leadership philosophy. In 1957, along with Bayard Rustin and Stanley Levison, Baker co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As a field organizer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), she traveled extensively throughout the South to organize local NAACP chapters.

From her travels, Baker came to recognize the collective power of communities and the importance of their participation in decision-making processes that affect their lives. These methods of organizing did not sit well with the other leaders of the SCLC, who were accustomed to a “top-down” approach. Baker challenged this practice with her understanding of how individuals can find empowerment through direct participation. Thus, they do not depend on the direction of a larger, outside institution but they find the resources within themselves first to address injustice in their community.

Baker found that the SCLC’s hierarchies within its organizational leadership conflicted with her philosophy. She said “In organizing a community, you start with people where they are.” She believed that individuals and communities already had resources and strengths that could be harnessed for collective liberation.

Additionally, Baker had disagreements with Martin Luther King Jr.’s leadership, because the SCLC relied so heavily on him as a sole leader. She knew the dangers of having a singular person portrayed as the face of a movement. Many of her ideas and suggestions, which called for the engagement of youth and women in organizing, were also overlooked, because they were voices of a black woman in a male-dominated space.

In the 1960s, Baker witnessed the organizing power of students in North Carolina. Following the example of 1940s and 1950s sit-ins in cities such as Chicago, Baltimore, and St. Louis, black students in Greensboro, North Carolina, used nonviolent protest to desegregate Woolworth lunch counters. The four college freshmen, now known as the Greensboro Four, were joined by other college students in daily sit-ins which drew national attention to the segregation in the South. They unveiled the curtain to the violence that white people would inflict to maintain segregation and racial inequality.

The grassroots organizing that these students were engaging in drew Baker to them and led to the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Baker supported the student organizers working independently of SCLC because she knew that the youth needed to have agency in the direction of their organizing. Her advising influenced SNCC’s major role in the civil rights movement. Using Baker’s framework, SNCC was able to do much of the radical work that SCLC could not.

As we reflect on the legacy of Ella Baker, one of the most influential people in civil rights movement, we must consider how her framework exists today. The Black Lives Matter movement is strategic in moving away from single, national leaders. Rather, the movement encourages black communities to address issues that are affecting them locally. As such, black communities can have more agency in how they address injustices in their neighborhoods. This group-centered leadership where members work together to assess how they respond and organize is one of the main elements of Baker’s framework of participatory democracy.

Similarly, we can look to United We Dream as another example of an immigrant, youth-led movement. It includes a network of immigrant-rights organizations across the country that uses localized systems of political action to push for a comprehensive immigration reform. They, too, engage in decentralization and collective decision-making by training young people to organize in their communities through an intersectional analysis of immigrant and LGBTQ+ struggles.

We are also seeing the activism of the Parkland survivors and the obvious pressure they have placed on elected officials and corporations. They have helped mobilize another wave of young organizers. In various cities and states, Memphis included, students are coordinating with the National School Walkout to call for gun control. The mobilization is happening at a local level, with groups deciding on their own what type of demonstration suits them best. For this generation of organizers, I offer the advice that was offered to me: Find and work from the strengths within you and your community; seek guidance when you need to, but trust yourself; do not be pacified, do not be co-opted, and do not give up.

In the words of Ella Baker, “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.” We are all agents of change. Adelanté. Aylen Mercado is a brown, queer, Latinx chingona pursuing an Urban Studies and Latin American and Latinx Studies degree at Rhodes College. A native of Argentina, she is researching Latinx identity in the South.