Robert Gordon is a different sort of music writer. With an investigative journalist’s penchant for going down dark corridors, knocking on closed doors, and driving the back roads, he’s brought readers a fresh perspective on regional artists who have been neglected, forgotten, or misunderstood. His first book, It Came from Memphis, had a companion CD that was an artfully crafted stroll through Memphis history, with a sublime rant by Dewey Phillips followed promptly by Mud Boy’s “Money Talks,” and so on through the hills and valleys of Bluff City obscurity. When William Eggleston released his first album of original music last year, Gordon’s readers and listeners already knew what to expect: he had featured Eggleston’s “Symphony #4” on this compilation over 20 years earlier.

So it comes as no great surprise that with the publication of Gordon’s latest book, Memphis Rent Party, comes another musical anthology under the same title, this time as a vinyl LP on the Fat Possum label. While the platter, like the collection for his first book, contains Memphis rarities galore, it is not as eclectic as its predecessor. There are no equivalents to Drive Inn Danny’s “Rocket Ship Rocket Ship” or the Eggleston symphony. But if this release is a more consistently rootsy affair, it offers many gems.

The first track, Jerry McGill’s “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” is a rich slice of the early ’70s Memphis scene, a Guy Clark tune transformed by a ne’er-do-well and his band of gypsies. As documented in the film Very Extremely Dangerous, by Gordon and Paul Duane, McGill was a real life desperado not unfamiliar with the slammer. The grit in his voice was hard-won, and well-complemented by the players: some of Mud Boy and the Neutrons, Ry Cooder, and Alex Chilton on background vocals. Though this was released with other McGill tracks on a CD accompanying the film, now will be the first time many listeners hear this ragged-but-right epic.

Other tracks tread more familiar ground. Luther Dickinson and Sharde Thomas, carrying the flame of her grandfather Otha Turner, take the allure of North Mississippi hill country fife-and-drum music to new heights with Dickinson’s blues guitar and a musical dialogue between the two singers. We can eavesdrop on Junior Kimbrough and Furry Lewis playing in their homes, though the former captures Kimbrough live with a full band in the midst of a swinging house party. Guitar great Calvin Newborn, who deserves a much deeper recorded catalog, can be heard swinging a “Frame for the Blues” in another live recording, this time from the Levitt Shell.

Side two opens with an even rarer live track, Alex Chilton spontaneously leading midtown regulars the Randy Band through the rock steady hit, “Johnny Too Bad.” It captures the focus and wit of Chilton, even in the midst of his ramshackle late ’70s Memphis period, simultaneously off-the-cuff and well-studied. He knows his songs, seemingly savoring every choice lyric.

One of the most powerful revelations comes from Jerry Lee Lewis, who cut “Harbor Lights” and other songs with Knox Phillips on a lark, to blow off steam while feeling straight-jacketed by his label during his country period. Unreleased until 2014, these early-mid ’70s tracks capture the Killer in raw, unfiltered sessions. This track in particular is a rocking re-do of a tune usually sung as a brooding ballad, nearly punk in its intensity.

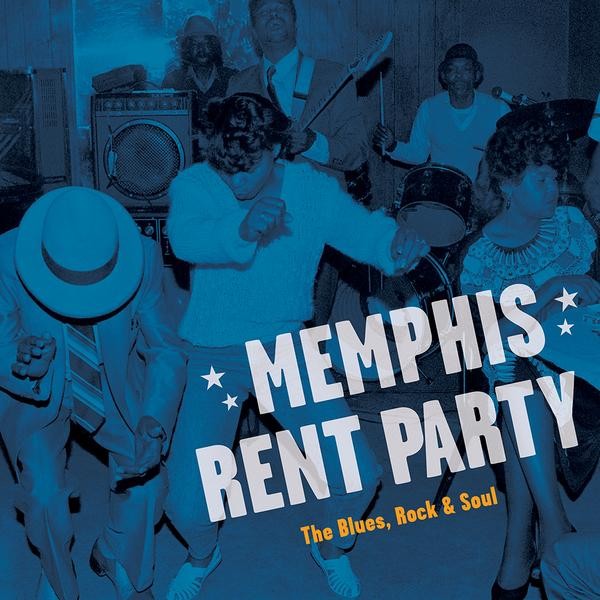

Fans of the now defunct blues club, Green’s Lounge, will love this LP, not only for the slice of 1989 captured in Gordon’s cassette recording of the Fieldstones’ “Little Bluebird,” but for the album cover itself, an image of dancing abandon from the club in the same era. Still more of the live Memphis experience is evoked with a very early Tav Falco & Panther Burns recording, possibly from the Well (later known as the Antenna), featuring a tango graced with the synthesizer squalls that the group largely dropped in their later sound palette.

Finally, a trio of studio recordings round the record out. Mose Vinson played his classic boogie woogie piano around town for decades, but wasn’t properly captured on tape until 1996 sessions at Phillips. One such tune is presented here, a welcome taste of piano in this rather guitar-centric collection. The LP then jumps back forty years to a 1955 session by Charlie Feathers for Sun Records, his earnest-yet-loopy “Defrost Your Heart.” It’s a country gem, Feathers briefly setting aside his rockabilly shoes. And finally, coming full circle with a return to the Mud Boy sound, so to speak, is Jim Dickinson’s tongue-in-cheek “I’d Love to Be a Hippie,” reminding us that, from the very outset, real hippies only adopted that tag semi-ironically. It’s a fitting set-closer, evoking, as does much of the book, the wild and wooly spirit of bohemian Memphis in the ’70s and ’80s, where counterculture freaks became the chief guardians of the old, creaky roots of our boogie roots.