Impressionism: Barbizon Paintings from the Walters Art Museum” at the Dixon Gallery & Gardens is an elegant exhibition rich in insight regarding how a loose-knit group of friends, known as the Barbizon painters, impacted the way we look at art.

All the key players are here: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, Gustave Courbet, Jules Breton, and Rosa Bonheur, one of the most noted female painters of the 19th century.

Because Corot and the other Barbizon painters wanted to experience nature up close and personal rather than filtered through the mists of time or the noble deeds of the powerful, they fled a sooty, fetid, politically unstable Paris for Barbizon, a tiny village bordering 45,000 acres of wilderness known as the Forest of Fontainebleau. With sometimes loose and spontaneous brushwork, they attempted to capture the ever-shifting patterns of atmosphere and light in Fontainebleau’s ancient woods, rocky gorges, and marshy flatlands.

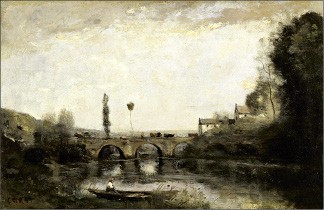

There are elements of Romanticism and classicism in Souvenir of Grez-sur-Loing, Corot’s serene, soft-edged, silver-toned painting of a medieval church and stone bridge, while Rousseau’s large, looming masterwork The Frost Effect pulls us into a wide expanse of frozen fields north of Paris. The horizon, directly ahead, is nearly black. Above us, windswept, golden-red clouds race like flames across the sky. Rousseau’s staccato brushwork allows us to feel as well as see nature’s immense energy and the sharp edges of the frozen earth.

In between the serene, silver tones of Romanticism and the light-filled landscapes of the Impressionists, Rousseau and the rest of the Barbizon painters forged a vision that brought them face to face with an implacably fierce and beautiful world.

Through January 11th

The comprehensive, beautifully mounted exhibition “The Baroque World of Fernando Botero,” at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, explores the genius of a sometimes misunderstood South American master best known for his oversized human figures that speak of the exuberance, the excesses, and ultimately the indomitability of the human spirit.

The 100 paintings, drawings, and bronzes selected from Botero’s extensive private collection include many of his masterworks, such as the frighteningly expressive 1959 painting, Boy from Vallecas, in which the features of a dead child appear to dissolve and flow down his misshapen face.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Souvenir of Grez-sur-Loing (ca. 1865-70);

The thin line between ripeness and rot is signified by the tiny worm that has eaten its way to the surface of Botero’s massive, pulpy, pale-green 1976 painting titled Pear.

Botero transforms a brothel in a small provincial town in his 2001 painting The House of Marta Pintuco into a memento mori and morality tale by introducing, at the far right, a cross-eyed baby sitting on the floor, unattended. Far left, an old woman, with a poignant expression of wistfulness and regret, looks through an almost closed door at the prostitutes and their clients eating, drinking, smoking, sleeping, and taking turns lovemaking.

Botero’s 2004 graphite drawing A Mother compresses into one image the terror and violence in Botero’s homeland, Colombia, a country torn apart by drug wars and extreme political factions since the 1960s. In this work, a woman lifts her child, throws back her head, and wails.

Trapped by pomp and circumstance, puffed up with self-importance, and dressed in the full regalia of royalty, the princess Margarita inflates to the point of bursting in Botero’s signature painting After Velazquez.

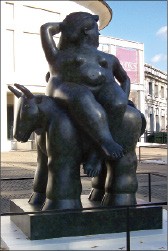

Some of Botero’s largest, most profound, and sensual works stand in front of the museum. The one-ton, seven-foot-tall bronze The Rape of Europa reenvisions the myth of the maiden raped by the god. Instead of whisking Europa away against her will, in Botero’s version of the story, Jupiter, who has transformed himself into a bull, stands powerful, patient, and ready. Europa caresses the bull’s rump with her left hand, strokes her own hair with her right hand, and twists in the direction of Botero’s nearly 12-foot- long Smoking Woman whose mounds of Rubenesque flesh look as soft as the bedding on which she lies.

Nearby is the 10-foot-tall bronze sculpture Hand with beautifully shaped, slightly bent fingers that appear to caress the air. This could be Botero’s ingenious portrait of himself as well as all painters/sculptors who sense the world with their fingers as well as their eyes.

Sunlight plays across the polished peaks and valleys of all these bronze forms. Their green and golden-brown patinas are earthier and more sensual than the paler, porcelain complexions of Botero’s paintings. Surprisingly, these huge metal sculptures are some of the most electrically charged, alive works of Botero’s career.

Through January 11th

Fernando Botero, The Rape of Europa (1999)