At times, the January 9th town hall meeting held in Harriman, Tennessee — hosted by celebrity environmentalist Erin Brockovich and set against the panic and uncertainty of a massive environmental calamity — resembled an episode of The Simpsons, TV’s long-running satire about a typical “nuclear” family living in a radioactive city where the fish have three eyes.

One woman worried that cleaning up the Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) massive coal-ash spill might disturb all the barrels of toxic waste rumored to be buried under the sediment.

A man in a wide-brimmed hat offered to donate the misshapen body of his tumor-ridden, river-loving dog to science as soon as the poor thing died.

A nattily dressed man with snow-white hair waited patiently, then, when he got his turn at the microphone, erupted like a volcano: “Who can I trust? Tell me, who can I trust?” he asked, his voice quivering.

The man ran down a list cataloging the incongruous viewpoints he’d been subjected to for 18 days — the time that had passed since the waste-retaining wall at the TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant gave way, and his hometown — once a water-lover’s paradise tucked into the postcard-perfect hills of East Tennessee — became the new synonym for environmental disaster.

“Tell me who I should trust,” he pleaded, obviously doubtful that Brockovich or the panel of scientists — and legal consultants from New York’s Weitz & Luxenberg law firm — assembled in the gymnasium at Roane State Community College were less self-interested than the environmentalists, media, or coal-industry spokesmen, all of whom seemed to offer conflicting answers.

The question captured the full attention of a room packed with people who’d come looking for clarity and hope. Instead, they got a nostalgic, student-produced film about life in Roane County, some sound legal advice, and a few heartfelt testimonials assuring everyone that, in spite of their reputations, lawyers often do help people.

“‘Who can I trust?’ was the most prescient question anybody asked,” said Owen Hoffman, an expert in risk analysis who brought a scientific perspective to Brockovich’s panel discussion.

“The ties between government and industry have been too close for many years,” Hoffman said, “so it’s not unreasonable to wonder if the information we get from our government agencies is reliable.”

Hoffman is the president of SENES Risk Management in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and has worked in risk assessment for 30 years. He understands the hard science as well as the social dynamics of the current Kingston situation. He knows that environmentalists are accustomed to thankless uphill struggles and can be counted on to accentuate the negative and that industry spokespeople and real-estate developers will tend to “trivialize” realistic consequences to protect financial interests — interests that in this case are clearly threatened.

What residents want desperately to know, of course, is what the long- and short-term consequences of the spill will be. So far, the answers to those questions depend on who you ask.

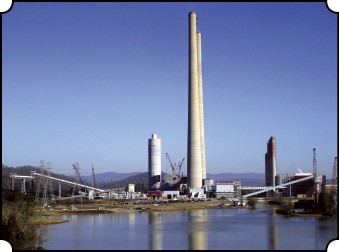

ON DECEMBER 22ND, RESIDENTS OF KINGSTON got a Godzilla-sized lump of coal in their Christmas stockings. When TVA’s dike burst, the contents of a 40-acre pond shifted and more than a billion gallons of pale gray coal sludge poured out, contaminating miles of the Emory and Clinch rivers and turning a 300-acre stretch of the Swan Pond community into a desolate moonscape.

On December 24th, NBC Nightly News termed the disaster a “toxic mess” and described it as “30 times larger than the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster.”

“What does that mean?” Hoffman asked. “Yes, health risks may be elevated, but no, I haven’t seen anything yet that says we have to evacuate the community. … When we are exposed to suites of contaminants, it’s not enough to say the concentrations are all above or below a certain level. We also have to ask questions about how all of these things act together?

“One thing we do know for certain is that the magnitude of the spill, the area spread, and the tonnage is tremendous,” Hoffman continued.

by Chris Davis

by Chris Davis

Shea Tuberty, a professor at Appalachian State University, worked with his colleague, Carol Babyak, and Watauga riverkeeper Donna Lisenby to collect and examine samples of water and wildlife in the affected area immediately after the spill. Tuberty calculates that in addition to the liquid content of the spilled slurry, more than 200 million gallons of solid waste were released into the environment.

“That much bulk, according to my back-of-the-envelope figuring,” said Tuberty, “adds up to 1,035 tons of trace metals.” Tuberty noted that recreational facilities in the area are already posted with signs warning of the mercury content in fish. In addition to Mercury, coal fly ash also contains arsenic and other potentially hazardous components.

“Exxon Valdez doesn’t compare,” Tuberty said. “And other ash spills have only been one-tenth to one-hundreth the size of this spill.”

Hoffman has publicly cited Tuberty’s and Babyak’s data showing that elevated levels of arsenic can be found miles down-river from the spill. Although newer data coming from TVA and other sources suggest that the levels are lower than those found by Tuberty, Hoffman says the Appalachian State data are still comparable and useful.

“The water samples used in the tests done by Appalachian State were taken right out of the river,” Hoffman said. “So, as drinking water, they represent a worst-case scenario since nobody is going to drink water directly from the river. But as a measure, it’s not off the wall. In a regulatory sense, treating river water like drinking water is a benchmark, because pets and livestock consume that water. In that sense, it’s not unreasonable.”

“Catfish eat all sorts of things off the bottom,” Tuberty said. “Stonefly larvae will live in the sediment and emerge as adults to be eaten by other things. As we work from bottom to top, the toxicity concentrates.”

Tuberty and Babyak also collected dead fish, looking for toxicity and stress levels. Although results aren’t yet available, there already have been some surprises.

“One catfish had 37 grams of ash in its gut, 8 percent of its total body weight,” Tuberty said. “I weigh 167 pounds, so that’s like me eating 13 pounds of the stuff.”

Samples taken with a dredge in the Emory River suggest that sediment from the spill ranges in depth from four meters near the spill site to eight-and-a-half inches two miles downriver. Six-and-a-half miles away, in the Clinch River, the sediment levels reach up to one-half inch in depth.

For many residents of the Swan Pond community, the effects of the coal-ash spill are more obvious and immediate. Bridget Daugherty described the filthy wall of displaced water that crashed over her house as a “tsunami.”

Bob Christie, who lives 300 yards from the spill site in a residential cove that is still covered in ash, was trying to sell his house before the disaster hit. He complained to Brockovich’s panel that his $400,000 property is now worthless.

by Chris Davis

by Chris Davis

Erin Brockovich

J.T. Melton claimed that his fly-ash allergy is so severe that he’s going to have to move, whether he can sell his home or not. “I have to leave this area, which means I’ve got to keep up two homes,” he told a representative of Weitz & Luxenberg. “Is there anything I can do?”

Peggy Adkins didn’t attend Brockovich’s meeting to complain about how the current ash spill had affected her. She came instead to show the crowd what exposure to heavy metals over time can do to the human body. Adkins, a Roane County resident who is wheelchair-bound with nerve damage in her lower extremities, told the Flyer she was exposed to the toxins by “air, water, fishing — and by irrigating my 4-H projects.”

ON THE NIGHT BEFORE Brockovich’s meeting, another group of scientists held a different kind of gathering at Kingston’s Midtown Elementary School. Consultants from the American Coal Ash Association (ACAA) hosted a meet-and-greet event that included a massive buffet table weighted down with shrimp, meatballs, croissants stuffed with chicken salad, fruit, pastry, cookies, and a selection of exotic cheeses.

There was no official presentation, but Kingston residents could walk around and ask questions of the ACAA’s scientists.

“I think the public has been very poorly informed,” one toxicologist said to a reporter in the crowd. “It’s wrong to characterize the ash as toxic sludge. That’s a pejorative term. It’s like my wife complaining that she had to drink toxic sludge because she recently had a gastrointestinal exam and the doctor made her swallow barium.”

There was also a medical doctor on hand to address — and minimize — concerns about long-term health risks and a coal-ash expert who explained how using fly ash in concrete helps mitigate the greenhouse gasses released in the coal-burning process.

“I don’t think anybody’s going to see Blinky the three-eyed fish in the river,” said Dr. Michael Bollenbacher, a radiation expert and the one showman among the ACAA’s consultants. He took on tough questions from Harriman resident John Hoage, a retired attorney who has sued tobacco companies.

Bollenbacher’s reference to Blinky was likely a response to the opening paragraphs of a 2007 article in Scientific American called “Coal Ash Is More Radioactive than Nuclear Waste” that had been making its way into e-mails all over Kingston.

Bollenbacher worked the crowd like a blackjack dealer, running a pair of Geiger counters over bags of local dirt and coal ash, as well as over typical household objects. The dirt and coal ash triggered little response from the machines, while the household objects made them screech.

by Chris Davis

by Chris Davis

TVA’s December 22nd coal-ash spill attracted an array of scientists, attorneys, politicians, and provocateurs to Kingston, Tennessee, including environmental advocate Erin Brockovich who hosted a town hall meeting.

“Did you hear what happened when I held it over the plate?” he asked, as if the red Fiestaware on the table was typical of contemporary kitchenware. But red Fiestaware, which hasn’t been produced for decades, is somewhat infamous for containing uranium and lead that can be leeched out by acidic foods such as tomato sauce.

“But what do I know about any of this?” Bollenbacher asked rhetorically. “I’m just a dumb scientist, an independent consultant who doesn’t have a dog in this fight.”

Attorney Hoage was not easily deterred. He pulled out a folder of information he’d collected about the ACAA. He said the organization’s membership page reads like a Who’s Who of coal industry heavyweights. He said he didn’t think anybody was telling him the whole truth.

“All of this reminds me of the 1950s,” Hoag continued. “The tobacco industry had scientists, too, and they used similar arguments to minimize the risks of cigarette smoke.”

The attorney recounted how studies funded by the tobacco industry were used to discount fears about secondhand smoke. “But flight attendants, who were stuck in these big tubes breathing other people’s smoke, eventually got lung cancer.”

BRYCE F. PAYNE, A CONSULTING SOIL scientist with Soil Ecosystems Services Inc., is a coal-ash expert who isn’t consulting with attorneys or working with TVA. Although his observations are informed and objective, he cautions that he’s making them from afar.

“I could dream up a scenario that would be worse,” Payne said of conditions at the Kingston site. “Based on my years of experience with coal fly ash, it’s not a hazardous material. But loose in the environment, it can cause problems.

“This a good news/bad news situation,” Payne said. He described coal fly ash as made up of small, almost perfectly round hollow or solid beads. Some of the beads are tiny black pieces of unburned carbon; others are magnetite, a dense magnetic iron compound. The bulk of coal fly ash consists of light-colored or clear beads of silicon aluminum-oxide glass.

“There will be little risk of dusting problems from the ash under winter weather conditions,” Payne said, “except for some of the low-density cenospheres, which will move in the wind under almost any conditions.” Payne also said conditions could change in warmer weather.

Payne generally seemed to agree with the ACAA scientists, who described coal fly ash dust as more of a nuisance than a hazard.

“Coal fly ash particles are smooth, round, and carry no readily soluble or absorbable toxic components,” he said. “For 10 years, I have observed and worked with plants and animals that live in and on coal fly ash, some for more than 40 years. On my reclamation sites, there are flocks of wild turkey that would dust-bathe daily in dry coal fly ash. I have never been able to identify any harm to the plants or animals living in or on these soils.

“Nevertheless, due to its small particle size, coal fly ash dust can be expected to cause irritation of mucous membranes and related respiratory problems, especially for those with pre-existing respiratory conditions,” Payne said.

Payne described a 40-acre pond of coal fly ash near one of his work sites that has developed a large carp population. The pond, he said, is a popular resting area for migratory waterfowl, including ospreys that have nested in the area.

“If the level of arsenic or selenium in the coal fly ash pond water were present at biologically important levels, then the ospreys should have had obvious health and reproduction problems, even if they only occasionally consumed carp from the CFA pond,” he said.

But Payne is no Pollyanna, and the bad news is pretty bad.

by Chris Davis

by Chris Davis

“Among humans, the tolerance for exposure to toxic elements can vary widely,” he explained. “Some can tolerate high exposures, some only very limited exposures. The same is true among plants and animals. Carp are a rough fish species, tolerant of pretty poor water quality. Other fish species cannot tolerate conditions that carp thrive in.

“In all likelihood, the greatest environmental release of toxic elements occurred at the time of the ash spill and has already begun to decline,” Payne said. “However, due to the environmental chemistry of coal fly ash, there is a real possibility there will be subsequent temporary increases in the levels of some toxic elements. If those levels occur, it is highly unlikely they will last for extended periods.”

According to Payne, coal fly ash particles can potentially present a fairly significant inhalation risk, since the thinnest-walled cenospheres can occasionally fracture into microscopic glass shards, like shattered Christmas ornaments. “Such microscopic glass fragments would be extremely sharp,” Payne said, and could present considerable potential for cell injury to mucous membranes “if there were significant or prolonged exposure.” This risk, he said, “is probably actually quite limited, because only a small portion of cenospheres are likely to fracture.”

“There are a number of toxic elements in coal fly ash at somewhat elevated concentrations,” Payne said. “My experience has been that the release of toxins directly from coal fly ash as it weathers is so slow that they rarely accumulate to harmfully active levels,” he said. “On the other hand, if coal fly ash is stored in, say, a pond, it will weather to form new minerals [that are] stable in the pond environment. As long as the ash and its weathering product minerals remain in the pond environment, the toxins are retained, because they have weathered to a form that is chemically stable in the pond environment.”

If the ash is released from the pond and exposed to substantially different environmental conditions, as happened in Kingston, however, Payne thinks there is then a substantial chance that the previously stable elements will become unstable. If that occurs there could be a net release of the toxins “that will accumulate to potentially threatening levels.”

So, what’s in store for the residents of Kingston as environmentalists and attorneys square off against the coal industry and helicopters fly overhead, spreading hay and grass seed over the thick gray sludge that has brought so much attention to the community? Unfortunately, if the experts can be trusted, nobody knows for certain. The truth remains buried in shades of gray.

What is Coal Fly Ash?

by Chris Davis

by Chris Davis

Coal fly ash is one of the residues generated in the combustion of coal. Fly ash is generally captured from the chimneys of coal-fired power plants and is one of two types of ash that jointly are known as coal ash. The other type, bottom ash, is removed from the bottom of coal furnaces. Depending upon the source and makeup of the coal being burned, the components of fly ash vary considerably, but all fly ash includes substantial amounts of silicon dioxide (SiO2) (both amorphous and crystalline) and calcium oxide (CaO). Toxic constituents include arsenic, beryllium, boron, cadmium, chromium, chromium VI, cobalt, lead, manganese, mercury, molybdenum, selenium, strontium, thallium, and vanadium, along with dioxins and PAH compounds.

In the past, fly ash was generally released into the atmosphere, but pollution control equipment mandated in recent decades now requires that it be captured prior to release. In the U.S., fly ash generally is stored at coal power plants or placed in landfills.

by Chris Davis

by Chris Davis