Just before 8 o’clock on a blustery January morning, about 50 men and a few women gather on the front porch of a modest house on Jefferson Avenue in Midtown. Some are bundled in coats, scarves, and hats, while others wear only ragged jeans and too-thin jackets.

Inside, volunteers of Manna House, a hospitality facility for the homeless, are preparing to open the doors and welcome a small group of the city’s chronically destitute.

One volunteer offers to man the coffee station, while another holds a jar of vitamins to hand to those in need of proper nutrition. Another person volunteers to staff the laundry room, where homeless folks can trade their dirty togs for clean, used clothing and socks.

Manna House head volunteer Peter Gathje, a tall man with gentle eyes and a shaved head, leads the group of 20 or so volunteers in a short prayer, as they hold hands and stand in a circle.

When the “Amen” has been delivered, Gathje opens the Manna House doors and shouts, “Good morning!” A cheerful “Good morning!” sounds from those gathered on the small porch.

One by one, the homeless pour through the front door to take in a few hours of warmth and hospitality. Some rest on tattered couches, while others stand and chat with volunteers.

Manna House, funded by donations from churches and individuals, offers the city’s homeless a place of welcome, at least for the few hours it’s open on Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday mornings. The rest of their days are often spent trekking back and forth between downtown and Midtown, seeking free food, spare change, and a place to rest.

“There are 1,800 homeless people in Memphis on any given day — at least that we can find,” says Pat Morgan, executive director of Partners for the Homeless, a nonprofit organization attempting to coordinate resources and services for the city’s homeless. “We know there are more than that, but we can’t find them.”

Morgan’s numbers come from a head count of homeless people on the street and in the shelters taken on one designated night each year. Though Partners staff and Memphis police check parks, alleys, and abandoned buildings (known as “cat holes”), it’s impossible to pinpoint the actual number of Memphis’ homeless population.

But one thing is certain: There aren’t enough resources for the chronically homeless in Memphis. The city is lacking permanent supportive housing for the low-income to no-income poor. There are very few shelter beds open to intact families.

Unlike many large cities, Memphis has no free shelters for men, yet men make up about 80 percent of the city’s homeless population. And based on recent spikes in shelter statistics — the Union Mission served 14,371 meals in February of last year compared to 18,094 in December — the economic downtown may be driving even more Memphians into homelessness.

Give Me Shelter

Bone*, a young man wearing silver rings on every finger, probably wouldn’t strike most people as homeless. But he’s been living on the streets, off and on, for four years.

“My grandparents raised me, and after they passed away, I ended up on the streets,” says Bone, on the porch of Manna House.

Bone has slept in abandoned houses and at bus stops. He stays at the Union Mission, the city’s largest men’s shelter, when he can.

“I prefer the shelter, where I don’t have to worry about getting robbed,” Bone says. “Ain’t nothing wrong with the Union Mission building. The problem is the other people in it. It’s better than being outside though.”

The Union Mission, a Christian ministry since it opened in 1945, provides 120 beds and 100 mats per night for men willing to listen to a sermon by on-site pastor Jeff Patrick. Each man receives four free nights of lodging, but every night after that costs $6.

The mission dishes out an average of 600 plates per day of free breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In addition to acting as an emergency shelter and soup kitchen, the mission also provides a residential drug and alcohol treatment program for the homeless.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Peter Gathje, left, volunteers at Manna House, a hospitality center for the homeless on Jefferson Avenue in Midtown.

“On some nights, we’ll have 250 people in here, but there’s no violence,” Patrick says. “The guys that stay here regularly love it because they feel safe.”

Other shelters — such as Midtown’s Living for Christ shelter, Peabody House, and the Salvation Army — provide emergency shelter for men or women, but most charge a nominal fee per night. In total, there are 1,126 beds for the homeless in Memphis, but some of those are reserved for people recovering from substance abuse and the mentally ill. Others are available only by referral from a nonprofit agency.

Yet some homeless people, like Mike, seek out alternatives to the shelters. In his mid-40s, Mike has been on the streets since September 2006, after he was released from spending a year in jail due to missing court on a DUI charge.

“I do my four free days at the Union Mission, but most of us would rather sleep outside than sleep there. It’s just too crowded,” Mike says. “I’ve stayed in cat holes. I used to sleep at the [temporarily closed] Magevney House, and it even had a bathroom.”

Those who do wish to sleep in a shelter will not only need $6 to $8 per night, depending on where they stay, but they’ll also need a picture ID.

“We help people get birth certificates, since picture IDs are required for shelter stays,” says David Figel, executive director of the Hospitality Hub, a point-of-entry center for the newly homeless. “To get an ID, you need a birth certificate, two letters (no older than four months to show residence), and a Social Security card. We let people open a mailbox here, and we send them two letters. The process takes about three to four weeks.”

The Hospitality Hub, located on Jefferson Avenue downtown and funded by the Downtown Church Association, provides access to computers, one free local and long-distance phone call per day, free books, and locker rentals so the homeless have a safe place to store their belongings. They also assist people in finding jobs, though with the economy in the dumps, that task has been more difficult.

“Jobs are becoming more scarce,” Figel says. “We used to have a list of day labor centers, but now day labor isn’t hiring as much. We really feel the cutbacks at this level.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

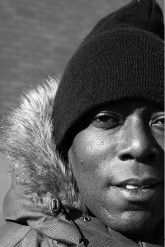

Bone

Power to the (Homeless) People

Homelessness can happen to anyone. Take Sam, a small-framed man who hangs out in Court Square. He attended college and says he was once an expert guitar player and a skilled electrical worker. But in August 2007, Sam was hit by a car. One of his hands was severely injured, and the medical bills began stacking up. Since he was uninsured, he eventually lost everything. His injured hand prevents him from doing the electrical work he once loved.

Now Sam lives on $675 a month in disability. Sometimes, when he has money left, he stays in cheap hotels. But he’s often forced to seek out a shelter bed or an abandoned building.

In the current economic crisis, stories like Sam’s are becoming more common. Patrick of the Union Mission says in recent months they’ve seen an increase in “East Memphis types who’ve lost it all” and checked into the shelter. The foreclosure crisis is putting more and more intact families on the streets.

“We’ve never had enough housing for families,” Morgan says. “We’re not serving the ones who need our help the most.”

Only women’s shelters accept children, so fathers are often separated from their families. The Union Mission does provide five fully furnished transitional homes for needy families, but there’s a waiting list.

In 2002, the Mayor’s Task Force on Homelessness, a group of service providers and government representatives, outlined a “blueprint to end chronic homelessness,” identifying key service areas that could use a boost. But, as Morgan indicated at a meeting of the Center City Commission in December, the plan hasn’t come very far in the past six years.

The blueprint lays out the city’s biggest needs for the homeless. Among them are filling housing gaps, developing safe havens of supportive housing, and providing more assistance for homeless people discharged from rehabs and hospitals.

“There’s still nowhere to house the medically fragile,” Morgan says. “The current emergency shelters can’t handle them.”

There hasn’t been much progress in filling housing gaps either. There’s currently no permanent housing for people with substance-abuse problems, but Morgan says Partners is working to develop apartments for people discharged from residential rehab facilities.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

David Figel of Hospitality Hub counsels one of Memphis’ homeless.

Though not outlined in the mayor’s plan, Jacob Flowers of the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center has long advocated for a large free shelter for males and females, similar to the Nashville Rescue Mission.

“I think a free shelter could be federally funded,” Flowers says. “Partners for the Homeless brings in money from the [Department of Housing and Urban Development]. Why can’t we put that money into a free shelter?”

But Morgan believes providing free shelters promotes irresponsibility among the homeless.

“If you work all day with a day labor crew and then you get paid and smoke it all up in crack, I’m not paying for your room tonight, thank you very much,” Morgan says. “We have to teach the homeless to be responsible and be good stewards of the money that people give us.”

But not all homeless people are on drugs. Tony, a middle-aged Vietnam veteran, doesn’t do drugs, but he’s currently homeless and out of work. With day labor jobs becoming scarce, it’s often hard to come up with shelter money without panhandling.

“Memphis is a bad place for homeless people,” Tony says. “The Nashville shelter is as big as a Home Depot or a Lowe’s, and it’s free. Most cities I’ve been to have free shelters.”

Flowers believes the answer to addressing the needs of the homeless lies in the formation of a homeless-run advocacy group like the Nashville Homeless Power Project.

The group, made up of homeless and formerly homeless people, has managed to secure $800,000 in Nashville city funding for 60 units of low-income housing, and they’re campaigning for more. The group also has registered more than 1,000 homeless people to vote, and they’ve trained Nashville police officers in how to deal with the homeless.

Each Thursday at Manna House, Flowers leads a discussion group with homeless people interested in advocating for their own needs, such as free shelters and an end to harassment by the Center City Commission’s public safety officers in Court Square. In addition to stopping panhandlers, the officers cite homeless people for public urination, cursing, and sleeping on park benches.

Flowers believes letting homeless people address their own needs could be more effective than waiting on the city to step up to the task.

“It’s not effective for us as privileged individuals to advocate on behalf of the less fortunate,” Flowers says. “We’re trying to identify people on the streets who can organize themselves around these very real issues, and we’re training them in grassroots advocacy. We have to address the root causes of homelessness if we’re ever going to truly fix the problem.”

* Some names of the homeless have been changed to protect their identities.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Jeff Patrick, pastor of the Union Mission on Poplar