Communities can’t heal from wounds of the past without facing them first.

That is the premise behind the Lynching Sites Project (LSP) of Memphis, which aims to memorialize the known lynchings in the Shelby County.

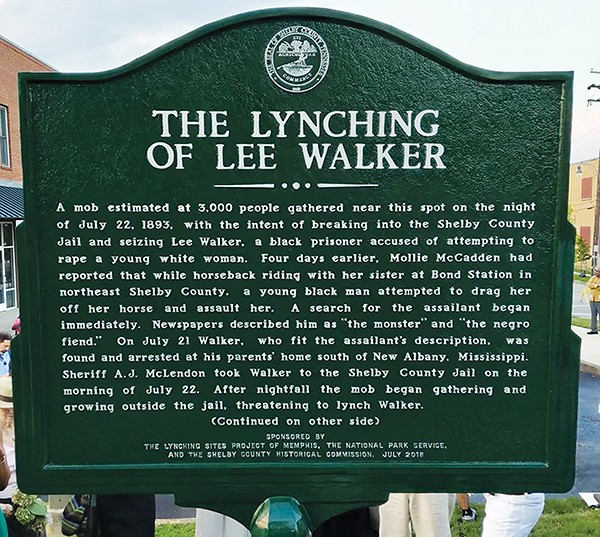

Over the weekend, the group and community members gathered to dedicate its third marker, which commemorates the 1893 lynching and death of Lee Walker. Walker, a young black man accused of sexually assaulting two white women, was dragged from the Shelby County Jail by a mob, beaten, and then hanged in an alley near A.W. Willis and Front.

LSP was formed about two years ago, and it’s comprised of residents who “want the whole and accurate truth” to be known about people like Walker and other victims affected by racially motivated violence in the county’s history. Jessica Orians, media strategist for LSP, said the goal is to have an accurate historical marker at each site.

Lynching Sites Project

Lynching Sites Project

marker for Lee Walker

“Without the Lynching Sites Project, these horrors of the past would never be known,” Orians said. “We try to make things right by telling the entire story.”

The group is actively searching for lynching sites based on the NAACP’s 1940 definition of lynching: “There must be legal evidence that a person has been killed, and that he met his death illegally at the hands of a group acting under the pretext of service to justice, race, or tradition.”

Shelby County has a recorded number of 35 lynchings between the Civil War era and 1950. That’s more than any county in Tennessee.

Margaret Vandiver is the lead researcher in charge of identifying the victims and sites of the county’s lynchings. By studying historical documents and old newspapers, as well as interviewing surviving family members, Vandiver and a team of volunteers “piece together the stories of the victims,” Orians said.

“It’s a tiring and critical process,” Orians said. “It’s just like detective work.”

Vandiver and team are in the process of identifying two more lynching sites, which are expected to be confirmed by the end of the year.

Orians said many people are weary of the group’s work, questioning if incidents like lynchings should be be dug up from the past. But, Orians said without the project, people would never know the truth of the past and the victims would remain nameless.

“We try to turn on the light of truth,” Orians said, quoting Ida B. Wells. “The way to bring about racial healing is to make these sites known to the public. It’s important to us that these atrocities in history that no one knows or talks about can be brought to light so we can learn and heal the present racial tensions.”

Orians said memorializing the “horrific events” aids in moving forward and bands people together, by creating a sacred place where people can learn and heal.

In addition to the group’s work at lynching sites, they also meet bi-monthly, facilitating “listening circles,” where community members can come and talk through racial issues. Orians said the goal of the meetings is to figure out ways to move forward and heal the “painful wounds of the past that people are still bearing.”