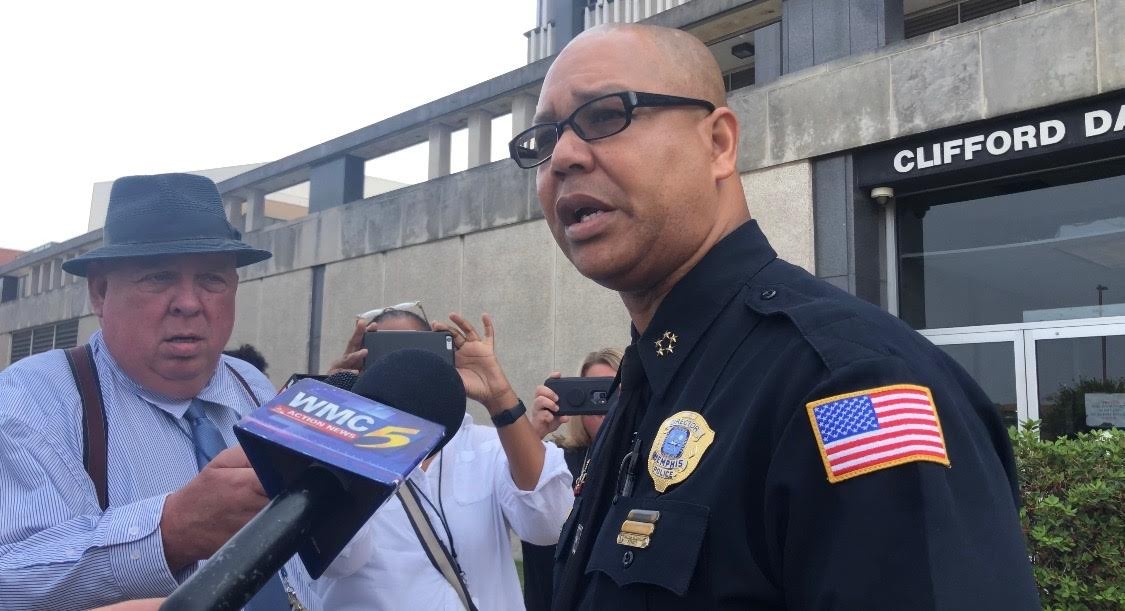

MPD director Mike Rallings

Memphis Police Department (MPD) director Michael Rallings wrapped up his testimony Wednesday morning in the federal trial on Memphis police surveillance.

Rallings said before this litigation began, he had “vague knowledge” of the 1978 consent decree, the issue at the center of the lawsuit. The decree, saying that the city would not gather political intelligence on non-criminals, was entered by the city with local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

When one of the lawyers from the ACLU-TN asked if the consent decree is covered in training material for officers, Rallings said he wasn’t sure, as there are “hundreds and hundreds of pages of policies and procedures.” But the decree is posted on the department’s kiosk, which is accessible by all officers.

“We didn’t care about that or spend a lot of time talking about it,” Rallings said of the consent decree. “Because we didn’t do that.”

Rallings emphasized throughout his testimony that the department’s motivation for monitoring social media and protests was to maintain public safety.

After the incident in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, Rallings said he “saw things ramping up” here and the department took a detailed look at how to allow citizens to exercise free speech lawfully.

“We respect the right to protest,” Rallings said. “We just want it done in a law-abiding way.”

Since then, Rallings said MPD’s intentions have been to assist protesters, but never to deter a demonstration. On the stand, Rallings testified that he can’t remember an incident where officers attempted to end a protest, whether it was permitted or not.

In monitoring social media for potential protests, Rallings said the content of the event or the associations of the organizers never played a role in determining the type of police response necessary. Instead, Rallings said the department monitored social media to ensure they could prepare and have enough resources ready to respond.

[pullquote-1]

Following the MPD shooting of Darius Stewart in 2015, Rallings said “things were getting heated” and the department was “extremely strained.”

Managing all of the events related to Stewart’s death with MPD’s limited resources was one of the key reasons for closely monitoring social media, Rallings said.

“We have to know what’s going on, so we can deploy resources,” Rallings said. “We’re not concerned with anyone’s beliefs. We’re concerned with protecting the public.”

On the stand, Rallings was asked to recall the day of the Hernando de Soto bridge protest in 2016, one he says “I’ll never forget.” He said he had an “aha moment” that day, as he realized the high potential for citizens and officers to get hurt.

He estimated there were about 1000 protesters on the bridge that day, and although the department would have been authorized to use tear gas or other means to disperse the crowd, MPD tried to use a minimal amount of force.

He said the officers showed an “enormous amount of restraint.” The event “was out of control,” Rallings said, and it could have easily turned “catastrophic.”

[pullquote-2]

“I thought that situation could have made Selma, Alabama look like a day in the park,” he said.

Following the bridge protest, Rallings said the department started looking at how to better manage protests to avoid future threats to infrastructure and public safety.

After his testimony, Rallings told the media that he “looks forward to working with the court in regards to the consent decree and moving on.”