Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

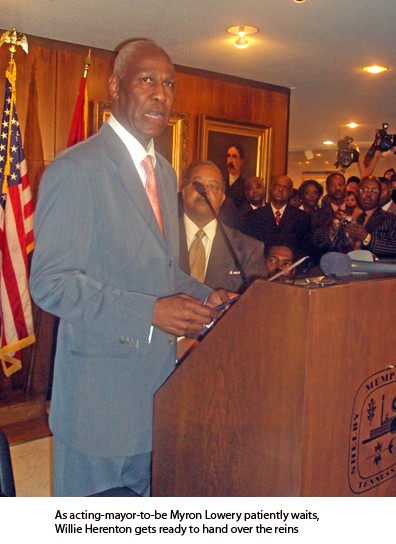

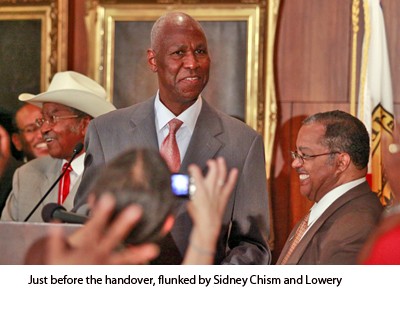

Let it be recorded that the very heavens opened when Willie Herenton left the job of Memphis mayor — for leave it he did, via a “retirement ceremony” in the Hall of Mayors, at the end of which he finally hand-delivered a formal letter of resignation to the patiently waiting city council chairman/acting mayor Myron Lowery.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Meanwhile, thunder and lightning and torrential rains and tornado rumors outside City Hall and throughout the city accompanied Herenton’s act of departure – appropriately enough, since the outgoing mayor (who won’t be excised from the city payroll until Friday morning) had declined to accept the role of unifier, pointing out during his retirement address in the Hall that “this city has never been unified” and that therefore his 18-year tenure could not be blamed for its disunity, and forswearing any intention to try to transform that fact when asked about it point-blank during the press availability that followed in the first-floor auditorium of City Hall.

Since Herenton had also made a point of telling the overflow audience in the Hall of Mayors that there was “only one human race,” his ultimate pitch to elect “someone who looks like me” for the 9th District congressional seat he intends to contest next year added to the general sense of an anomaly.

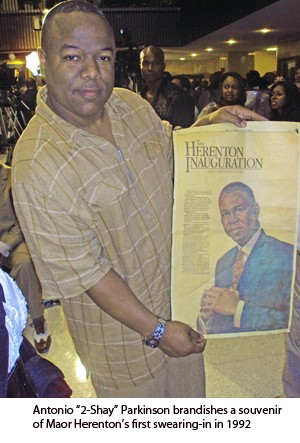

No matter. Mainly what Willie Herenton did on his final day in office was look back in satisfaction on his historical status as the city’s first elected African-American mayor, point with pride to what he regards as his major achievements (ranging from industrial recruitment to the FedEx Forum and the Grizzlies to improved public housing), remind Memphians everywhere of the city’s racist past, and celebrate one last emotional moment of bonding with the friends and supporters who had got him to City Hall and stayed with him through 18 years – sometimes triumphant, sometimes painful, always controversial.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Those friends included the Rev. Frank McRae, one of his few white supporters in 1991, the year Herenton was first elected; black businessman Luke Yancey, who had belonged to the former school superintendent’s corps of youthful backers that year; Keith McGee, the loyal CAO of Herenton’s last years; Rick Masson, his onetime CAO and chief finance officer; Shelby County Mayor A C Wharton, Herenton’s sometime campaign manager and would-be successor as mayor; and the Rev. James Netters, who delivered a final benediction.

Considering that the Hall of Mayors is essentially a small room, capable of holding a very few hundred people at elbow-to-elbow capacity, the catalogue of those present added up to a veritable Who’s Who of media, political, and civic types.

It also numbered a good many rank-and-file citizens – mainly Herenton admirers like 88-year-old Charlie Morris, a political and civic lion in North Memphis and a former amateur boxer like the mayor himself. Morris scorned those critics who “cast the first stone” and said he thought Herenton had been an unalloyed boon for Memphis. There were also detractors like Charlie Fineberg, the process server and sometime politician who stood a few feet away from Morris and condemned the reign of Willie Herenton as having lasted too long and become, not the cure for racism, but the means of exacerbating and perpetrating it.

Blogger Thaddeus Matthews, who in recent years has taken positions both favorable and highly unfavorable regarding the mayor, shrugged off the discrepancies as “all politics” and said, “No matter what you think about him, he made history for the African-American people.” All in all, said Matthews, he’d have preferred it if Herenton had stayed at the job of mayor longer.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

In his remarks, Herenton’s demeanor regarding himself was paradoxically both humble and immodest. He saw himself as having been a tribune of his people but could not resist, when speaking to the predominantly African-American crowd of the citywide quest in 1991 for a single black mayoral candidate “You put your very best forward.” Meaning himself, of course.

Considering the heavy emphasis given Herenton’s unique status as an African American chief executive by all speakers, including McRae and Masson, both whites, and by the mayor himself, it was something of an irony that Wharton chose to crown Herenton’s moment by reciting the concluding verses of “My Way,” a song written by one non-brother, Paul Anka, and made memorable by another, Frank Sinatra.

Almost as interestingly, there didn’t seem to be anyone in the crowd, black or white, who didn’t know the lyrics. By the time that Wharton had rounded to the last chorus of “I -did- it- my- way,” virtually everyone was chanting with him.

The mayor had honored his aged mother, who had a front-row seat in the Hall of Mayors, when he began his remarks in the Hall by directing the presentation to her of a bouquet. At the end of the ceremony, with a look in her direction, he visibly teared up. “They’re hating on your son,” he told her in one final reference to his critics.

At one point in his remarks, Herenton had noted the presence of son Rodney, with whom he intends to collaborate in business ventures even as he makes his promised run for Congress, but, after scanning the gathered throng, concluded that his other son, Duke, had not been able to leave his job to be present.

The mayor called out the names of those absent or present, living or dead, who had — as he told it — prevailed on him to run for mayor in 1991 when he had been initially reluctant to do so.

When the ceremony had ended and Herenton met for a brief availability with members of the press at the other end of City Hall in the council chambers, he reminded them that he had drunk from colored-only water fountains and sat in the back of buses but that his mother had fared worse – being denied the right even to try on the clothes she bought in the city’s downtown department stores.

Although in that final conversation with the press corps as mayor there was some banter back and forth, even a bit of heckling both ways, the affair was dominated by a general aura of respect. This was indeed a man who had traveled far and long, both in the personal and in the sociological sense, both for his own advancement and for the sake of his people.

As Herenton had pointed out several times in his remarks in the Hall of Mayors, there were no portraits hanging there of anyone “who looks like me.” Very soon there will be an exact likeness there.

After meeting with the press, Herenton prepared for a sit-down session with temporary successor Lowery, the better to review with him a list of “critical imperatives” which he had shared in outline with the crowd in the Hall. Some of the items on the list were traditional for any mayor of any city (“1. Promoting economic growth and development…5. Crime abatement strategies – both preventive and interventive….”), but many of them touched upon the peculiar local dichotomies of city/county and black/white.

Number six on the things-to-handle list he intended to pass on to Lowery said it all: “The racial divide: economic, social, political.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis