When it comes to the history of alternative music and culture in

Memphis, all roads lead to the fabled Antenna Club, a grimy black hole

of a bar once situated on the northwest corner of Madison and Avalon,

between a pawn shop and a dentist’s office that was also — most

conveniently — a leasing office for inexpensive Midtown rental

properties. The Antenna, widely regarded as one of the first and

longest-lived punk-oriented venues in America, closed 14 years ago. It

was a hub for creativity in Memphis and is being remembered and

celebrated with a 26-band concert August 14th and 15th at Murphy’s and

at Nocturnal, the site of the original venue.

When the Crime played the Antenna Club in the early 1980s, lines

would snake down Madison and spill around the corner onto Avalon. The

band, which featured guitars and vocals by Jeff Golightly and Rick

Camp, was a risky experiment in a city where all the good-paying gigs

went to top-40 cover bands. But Golightly and Camp, who still play

together in a multigenerational band called the Everyday Parade, were

on a quest to play new wave and punk music in Memphis and to eventually

write their own songs. Before long, they were touring and playing

bigger clubs and coliseums around the region. But no matter how big the

gigs got, they always looked forward to coming home to the Antenna and

to Memphis’ burgeoning punk-rock scene.

G. Brent Shrewsbury

G. Brent Shrewsbury

“We were part of somthing new,” says Golightly, who has a

conflicting gig and can’t participate in this weekend’s reunion. “The

folks we called ‘criminals’ were ready for us, and they were ready for

the scene that developed around the Antenna. The room is magical. We

packed the place on a regular basis, and the heat and sweat practically

made the place rain inside. When you put bodies in that space, the

sound was like nowhere else, and the Crime could make it pulsate.”

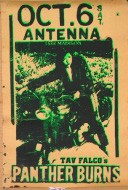

Panther Burns’ loquacious drummer Ross Johnson, who has attempted

but never finished a book on the Antenna Club, confesses, only somewhat

begrudgingly, that Golightly’s description of the early scene is

accurate. As a part of the snottier, noisier art-rock side of Memphis

punk, there was a time when Johnson couldn’t readily admit it was the

Crime’s smart power pop that kept the club’s doors open. “We could be

really cruel sometimes,” he says, remembering that he used to get a

kick out of sitting at the bar and heckling other bands. “Time softens

things,” he says, recalling the time he was thrown out of the club for

throwing a beer at his sometime-bandmate Alex Chilton.

Memphis’ punk scene got started in 1979, when the bar at 1588

Madison was still called the Well and local groups like Tav Falco’s

Panther Burns, the Randy Band, and the Klitz swapped out shows on the

weekends. In 1981, the property was sold to James Barker and Phillip

Stratton, who changed the name to the Antenna Club, painted the

interior black, mounted TV monitors on the walls, and started showing

RockAmerica music videos. They also started booking national acts.

Johnson says the videos, which were a novelty in 1981, a year before

MTV was available in Memphis, got old fast and that the outside booking

initially was met with resentment by locals, who liked having a

monopoly on the club’s stage.

When Steve McGehee, a former head waiter for TGIFridays, took the

club over from Barker and Stratton, outside booking became even more

aggressive.

“The club really started jumping, and more and more bands formed,”

Golightly says, recalling a period in the early 1980s when the Randy

Band’s bright pop and the heady new wave of Calculated X and Barking

Dog were showcased alongside the honky tonk swagger of Neon Wheels, the

privative stylings of the Klitz, and the noisy roots fusion of Panther

Burns and Milford & the Modifiers. “It was a scene where the famous

and the unknowns could share a stage,” Golightly says. “It was a venue

that would give any band a shot, as long as they brought a crowd that

drank some beer.”

The Antenna Club became as famous for the shows nobody saw as for

the ones everybody turned out to see. The first time R.E.M. played, the

club was barely able to scrap together enough cash to pay the band’s

$50 guarantee. McGehee remembers feeling completely alone while he

watched Mission of Burma play one of the greatest sets he’s ever

seen.

G. Brent Shrewsbury

G. Brent Shrewsbury

Alex Greene, a multi instrumentalist who’s played with Big Ass Truck

and Reigning Sound, was one of a handful of people who saw Detroit

garage legends the Gories when they played their first show in Memphis.

(A recent double reunion featuring the Gories and the Oblivians packed

the Hi-Tone to the point of discomfort.) And not every great show went

under-appreciated. “I believe we had the devil himself in here the

first night Black Flag played,” McGehee says.

In the ’80s, the Antenna became a regular stop for hardcore and punk

bands recording for Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn’s SST label, bands

such as Hüsker Dü, the Meat Puppets, the Minutemen, and Bad

Brains.

Johnson says the club probably owes its longevity to the enduring

nature of Memphis’ hardcore scene. He attributes much of the lingering

interest in the venue to its successful embrace of all-ages shows. Cult

filmmaker Mike McCarthy, whose band Distemper played the Antenna’s

first all-ages show, has a simpler explanation. “The great irony is

this,” he says, “if you were an alternative person in Memphis in the

1980s, you only had one place to go.”

In July, McCarthy, who once shot a horror movie at the Antenna Club,

spent three weeks touring his latest film, Cigarette Girl,

around Australia, where it premiered as part of the Revelation Perth

International Film Festival. In 1983, however, McCarthy had another

kind of road trip in mind. After visiting Memphis and taking in a show

by an edgy New Mexico power pop band called the Philisteens, the Tupelo

native decided to move to the Bluff City to attend art school and play

rock-and-roll at the Antenna.

“I sat terrified in the parking lot of River City Donuts, scoping

the place out, watching the toughest dude I’d ever seen in my life

walking into the club wearing a black leather jacket and a mohawk,”

McCarthy says. “Amid the disorienting TV screens with the Sex Pistols

doing ‘God Save the Queen,’ and lights that turned my teeth as green as

Johnny Rotten’s, I realized that the punk I’d seen outside was merely

the waiter, Steve McGehee. That night defined punk for me.”

Although the Antenna had a reputation for being a punk club, all

kinds of bands played there. Before he moved to Athens, Georgia, and

wrote “The Night G.G. Allin Came to Town,” Patterson Hood lived in

Memphis and played the Antenna with his band, Adam’s House Cat. Nancy

Apple, a driving force behind Memphis’ singer/songwriter scene,

describes the Antenna as a “country-friendly” establishment, where she

gigged with Linda Gale Lewis and Cordell Jackson, the rockabilly

granny. “I always felt like I had hit the big time when I played

there,” Apple says, allowing that her brand of twang was often referred

to as “cowpunk.” “It was one of those places where there was almost

always a great crowd, no matter who was playing.”

Even rappers played the Antenna. “Big Ass Truck would serve as a

backup band to various rappers [playing the Antenna],” says Alex

Greene, citing a gig the band performed with the young Al Kapone.

The 1990s saw new scenes spring up around the Grifters, a brooding

quartet that mixed angular, atmospheric indie rock with blues and metal

flourishes, and around garage-rock innovators the Oblivians and Impala,

surf-rockers with a flare for squalling crime jazz and dirty rhythm and

blues.

G. Brent Shrewsbury

G. Brent Shrewsbury

Shangri-La records founder Sherman Willmott, who produced many of

the Grifters’ first recordings, describes the Antenna as a place where

great shows received little or no promotion: “You always knew you were

going to be one of a handful of lucky people to see the best bands in

the world — like the Screaming Trees, the Chills, and Government

Issue — but you were never really sure if the band mentioned on

the club’s answering machine would play, when they arrived and saw a

broken sign, no posters for the show, a couple of underage girls, a

crazy looking doorman straight out of film-noir, punk-rock,

motorcycle-gang hell, and a couple Midtown hipsters hanging at the bar

watching RockAmerica videos and drinking stale keg beer.” Willmott

complains without actually complaining. “Only in Memphis could a club

run so poorly — no phone-answering, ever — survive for that

many years despite itself. God bless the Antenna Club, with all of its

open sores and decrepit beauty. It was like an alternative-universe

island in a nightmare town of classic rock.”

Like the King of Rock and Roll, who passed away after slipping from

his private Whitehaven throne in the wee hours of the morning, the

Antenna Club’s death was less than proud. A venue that hosted great

performances by the likes of Robyn Hitchcock, the Replacements, and

Suicidal Tendencies quietly closed following a poorly attended concert

by a disposable buzz band called Tripping Daisy.

According to the club’s last manager, Mark McGehee, who’d taken over

operations from his brother, Steve, things “went kind of sour” when he

told the band that he couldn’t possibly meet the pre-arranged $680

guarantee. Commercial Appeal reporter Larry Nager noted in an

article about the club’s closing that after combining monies from the

door, beer sales, and the cigarette machine, McGehee only had $400 and

that wasn’t enough to satisfy the band. That’s when McGehee decided he

was finished. When the media inquired, he told them the club had closed

because live entertainment was dying in Midtown. He added that

alternative music had become mainstream, and the Antenna Club had

outlived its usefulness.

But like a stubborn ghost, the Antenna Club never left the building.

The property’s next two incarnations, the Void and Barristers, were

short-lived alt-rock clubs in the mold of their famous predecessor. In

1997, the space was significantly renovated, decorated with

red-and-white candy-striped furniture, and rebranded as a tony lesbian

bar called the Madison Flame. The club’s owners would occasionally book

rock shows for Midtown bands and music fans, who regarded 1588 Madison

Avenue as holy ground. Nocturnal, the club currently located on the

site, features a regular slate of live music.

But this weekend, the ghost returns from punk purgatory, and the

Antenna Club will live once more — at least for a couple of

days.

The A List

Hundreds of bands played the Antenna Club. These are a few of

them:

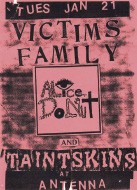

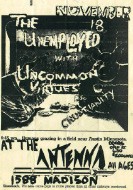

The Replacements, The Fall, Neon Wheels, Dead Milkmen, Suicidal

Tendencies, Mudboy & the Neutrons, R.E.M., Angerhead, Odd Jobs,

Pezz, The Bongos, The Randy Band, Adam’s House Cat, Widespread Panic,

Teen Idols, The Compulsive Gamblers, NRBQ, Greg Hisky, Guided by

Voices, Calculated X, The Gun Club, Trusty, Impala, Linda Heck &

the Trainwreck,The Hellcats, The Gories, The Verbs, The Country

Rockers, The Marilyns, Jason & the Scorchers, Mojo Nixon, Vibration

Society, The Oblivians, Gene Loves Jezebel, Black Flag, The Scam, Think

as Incas, Los Pimpin, Love Tractor, Flaming Lips, Metro Waste, Big Ass

Truck, G.G. Allin, The Modifiers, Paul Burleson, Man With Gun Lives

Here, Panther Burns, The Cadillac Cowgirl, Neighborhood Texture Jam,

Beanland, Crowded House, Circle Jerks, Alice Donut, The Bum Notes, The

Klitz, DDT, Hüsker Dü, The Generics, Sobering Consequences,

The Grifters, Econochrist, Meat Puppets, The Simpletones, Alex Chilton,

Hole, Bad Brains, Taintskins, Mission of Burma, White Animals, Royal

Crescent Mob, Barking Dog, Xavion, Bob’s Lead Hyena, The Crime, Robyn

Hitchcock, Busta Jones, The Minutemen, Webb Wilder, The Plimsouls,

Uncle Tupelo, Cordell Jackson, Green Day.