Where’s A C? By last week it was a ritual phrase in the campaign

— persistently intoned by Shelby County mayor A C Wharton’s

opponents at a variety of scheduled forums and debates to size up the

candidates for Memphis mayor.

Many of these affairs were well-attended — like the one

sponsored by several organizations and held in the Raleigh-Frayser

area, or another one held in Cordova under the auspices of the Cordova

Leadership Council. Others were held before smaller, specialized

audiences, like last week’s “green” debate at the University of

Memphis.

Mayor Pro Tem Myron Lowery was a regular at these events, as were

former City Council member Carol Chumney, current councilwoman Wanda

Halbert, and municipal bonds lawyer Charles Carpenter. Kenneth T.

Whalum Jr., a school board member and pastor of New Olivet Baptist

Church, was generally available, too, and a rotating cast of others

would check in: former county commissioner and perennial candidate John

Willingham, parks services employee Detric Stigall, or W.W.E. eminence

Jerry Lawler.

There are 25 names on the ballot overall. Some of them are well

known, like E.C. Jones, the former councilman whose decision to file

seemed to be a spontaneous emotional reaction to the sentencing of his

son Chris in a murder case, or Silky Sullivan, the Beale Street

restaurateur, or Robert “Prince Mongo” Hodges, the eternal

self-professed space alien whose act, like his eccentric wardrobe, has

a moldy look to it.

There are other names that tug at most people’s peripheral memory,

like perennials Johnny Hatcher and Mary Taylor-Shelby Wright (notorious

most recently for throwing water on her own lawyer in a courtroom) and

David Vinciarelli, still hopeful of getting a leg-up in some election

or another. There also are unknowns whose names conjured up parlor

games, like Leo Awgowhat (Knock knock/Who’s there?/Awgo/Awgo

who?) or the alliterative Vuong Vaughn Vo.

And there is at least one case — that of school board member

and former Charter Commission member Sharon Webb — of someone’s

losing a hold on identity in the very act of running. Webb’s dazy

know-nothingism outpointed even Mongo’s show-off rap for irrelevance in

the first showcase event of the special-election season, a late-August

debate on WMC-TV Action News 5.

That first TV debate also was the event that foreshadowed Wharton’s

intention to remain as elusive as possible, holding his participation

in group situations to the barest minimum while stage-managing

occasions that presented him on his own terms.

Take his “Sustainable Shelby” program, rolled out last month in a

public ceremony with the same kind of fanfare that had greeted such

other grand thematic approaches to problems as his Smart Growth

initiative of the mid-2000s and Operation Safe Community, which

addressed crime.

All well and good, but Sustainable Shelby dealt with environmental

questions in the macro manner. And, while nobody doubted that Wharton

knew his stuff on this issue as on most else that he might be asked

about, he was not on the scene last week at the University of Memphis

for a forum on green issues and therefore could not (or would not) mix

it up — either with his opponents or, potentially, with

questioners in his audience.

Beyond the matter of subjecting himself to barbs thrown by rivals

desperate to trip him up, Wharton also declined thereby to deal with

the specifics presented by other candidates. That night there was, as

always in forums of that sort, a certain amount of blather and sleight

of hand, in which the candidates dressed up their existing hobby horses

in green embroidery so as to pass muster as genuine environmentalism.

(Carpenter’s all-purpose “comprehensive plan” was so bedecked, as was

Whalum’s idea of dispersing city-government offices into

neighborhoods.)

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Candidate Carol Chumney takes the podium at the University of Memphis ‘green’ forum.

But there were also intriguing suggestions: Lowery’s for a monorail

system circling the city; Halbert’s for a return to cooking in school

cafeterias (instead of thawing and reheating pre-packaged products);

Chumney’s touting of gardens in vacated areas; Whalum’s call for the

Memphis Area Transit Authority to develop a bike-rental arm; and

Carpenter’s call for a thorough revamping of MATA’s antiquated

routes.

And it would have been interesting — and perhaps revealing

— to see how Wharton (whose knowledge of the general subject area

no one doubts) might improvise and ad-lib along with the others.

Long, tall, focused, and whip-smart — adjectives that could

also have once described former mayor Herenton, on whose coattails he

would come into prominence — Carpenter will likely not make it

this time around, but don’t discount him for 2010, when there’s a race

for county mayor, or in 2011, when there’s another one for city

mayor.

As he has so often noted on the stump, Carpenter is a home-grown

product, having ascended from humble beginnings in the downtown area to

get himself through Howard University and Notre Dame Law School. As he

so often has said, he came back home to find nobody wanted him, so he

hung out his own shingle. He already was on the rise, but his coming

aboard candidate Herenton’s campaign as its manager in 1991 allowed

him, after the upset win of the first elected black mayor in Memphis,

to apply his talents to large-scale urban projects, and his general law

practice rapidly escalated into one specializing in municipal financing

— a latter-day example of which involved bringing the FedExForum

project to fruition.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

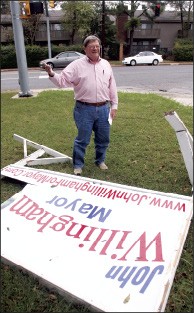

John Willingham checks on vandalized campaign signs on the corner of Colonial and Park.

His close association with Herenton is definitely of the

for-better-or-for-worse variety. Carpenter has disclaimed any

involvement in policy-making, and he notes that Wharton ran almost as

many of Herenton’s election campaigns as he did. He wants, he has

persistently said, to transition city government “from a political

culture to a business culture” and has meanwhile concentrated his

efforts on the larger Whitehaven area.

Carpenter’s public positions sometimes bespoke not only his

inner-city roots but his past relationship with Herenton, as if

unwittingly. Take his rejection of city/county consolidation, delivered

to several hundred attendees at the Breath of Life Christian Center in

Raleigh on September 21st: “I think this is one of the biggest

back-room deals in Memphis history,” he declared. After summarizing the

current plan as one in which the suburbs would retain their independent

schools and their municipal governments, while Memphis would dissolve

its separate governing institutions, Carpenter declared, “Let’s look at

the timing of all of this. Former mayor Willie Herenton has been

talking about consolidation for a decade. Nothing happens. He’s out of

office for 60 days, and there’s a plan!”

Back again for a second try at city mayor (she has also run once for

the county’s top job) is Carol Chumney, Herenton’s runner-up in 2007. A

veteran, as she invariably points out, of 17 years in public service

(13 as a state representative from Midtown, four as council member),

Chumney has succeeded to some degree in linking her public image to

what she perceives as the public’s desire for reform.

That goes even for her appearance. Gone is the sensible-shoes look

of 2007, her first try at city mayor. Some 30 pounds lighter and

considerably more fashionable in appearance, she is the would-be

leading lady of change in 2009. But she has been hampered.

Beyond the fact of her difficulty in raising money, Chumney

possesses two additional handicaps that did not exist for her in 2007,

when, in what amounted to a tripartite race with Herenton and former

MLGW head Herman Morris, she finished a strong second with 35 percent

of the vote, versus 42 percent for Herenton.

Two years ago, Chumney’s name was a household word. As an active

member of the council, she had stood out for her iconoclasm in all

matters and was among the first to challenge the infamous — and

soon discontinued — 12-year-and-out city pension arrangement. Her

talent was in finding the flaws in the usual. And, though she

challenged her fellow council members as often as she did the

administration, she had Herenton, whose reputation was in steep

decline, to kick around, and he made an admirable foil.

There was something retro and unconvincing about her pledge in this

year’s mayor’s race to “fight for you.” The slogan was appropriate for

a legislator, especially one who made a point of not going along to get

along. But it had an unduly reactive sound in the mouth of a potential

chief executive, whose charge was to lead — not to kick against

the pricks, as it were, but to coax them to come along.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Carol Chumney waves to passing cars at the corner of Park and Mt. Moriah.

Wanda Halbert, a first-term council member who served two terms on

the city school board, was a surprise entry for mayor, and she has been

woefully underfinanced, but she has been a dutiful candidate,

schlepping into as many open arenas and public forums as possible and

declaiming there an often detailed and quasi-revolutionary attitude

toward government.

Almost as persistently as Carpenter, she has noted what she

considers an injustice in the system — a preference, as she sees

it, for bestowing benefits on corporations and management firms rather

than on neighborhoods and the people who live in them. She is like

Carpenter, too, in calling for what they both call “tax equity,” a

revision of the relationship between city and county in which, they

both say, inner-city residents end up paying for their richer neighbors

of the county suburbs via a dual system of taxation.

The Rev. Kenneth Whalum Jr. has been nothing if not entertaining.

And his repetition of simple ideas in concrete terms is refreshing:

Restore Libertyland. Fire the “400 appointees” of the former mayor.

Disperse city offices into the neighborhoods. Lease office space in the

Pyramid to newly licensed doctors and lawyers on the proviso that,

within a set period of time, they, too, would hang their shingles in

neighborhoods. But, for all of the 83,939 votes he had won in his

at-large school board race, there was little sign that he had tapped

into a citywide groundswell.

“K.T. is running for City Council in 2011. You can count on it,”

said one of his rivals late in the game.

Perhaps that was too limiting. The charismatic pastor of New Olivet

Baptist Church could remain a vocal maverick on the school board, and

it was easy to imagine him mounting up for a serious challenge to

whoever would be the incumbent in 2011 — especially someone like

Wharton, whom he could clearly brand an establishmentarian.

I still wonder what might have happened if Jerry Lawler had done

some serious campaigning. Like Chumney, whose first and most serious

splash in a mayoral contest is evidently not to be repeated this time

around, Lawler’s first foray, in 1999, might have been his high-water

mark.

Granted, he only got 12 percent of the vote that year, but that,

too, was a multi-candidate race, with some serious big-name candidates

in it, in addition to the then still popular and high-flying incumbent

Herenton. And he had been restricted by a week-long schedule of

wrestling obligations from doing much in the way of campaigning.

This year, as he repeatedly said, his duties with the W.W.E. were

restricted to one night a week (Monday) on which he would fly to a

different American city, where he was responsible for some televised

wrestling commentary. Period. End of story. The rest of the time he

could devote himself to campaigning — though it would not be of

the conventional sort. After all, he was “no politician.” (A disclaimer

adopted also by Carpenter.)

Even so, Lawler should have given himself more of a chance to make

more elaborate sense of some of the issues: The Pyramid. Going green.

Urban blight and sprawl. As it was, he spoke in bromides: Allow people

to keep more of their money. Cut waste. Bring government to the people.

All well and good, and some, or all of it, was echoed by others.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Ray White campaigns for A C Wharton at the early voting station inside the Church of Christ on Colonial near Dee.

Late in the campaign — just this week, in fact — Lawler

hitched himself to an unlikely star, an education initiative chaired by

an ensemble including Al Sharpton and Newt Gingrich, two figures

unlikely to resonate anywhere, much less in a race for Memphis mayor.

However remote, however strangely authored, it was a bona fide

issue.

But essentially, all we had to go on was a man likable and

well-intentioned, intelligent, committed to Memphis, and certainly able

to do more than walk, chew gum, and sign autographs. But all of that,

and a good deal else, was spoken to by the apparent man of the hour, A

C Wharton, who, politician or no politician, was riding high in the

polls and was experienced besides.

A C Wharton is speaking in sound bites — in inaugural-sounding

snippets in TV ads which feature that famous uplifting persona of his:

“one Memphis.” Provide our police with the best technology possible. A

smiling, confident presence — one whose air of calm and

reassurance may be what the city yearns for after its 18 years of

experience with a sometimes inspiring, often abrasive Alpha male.

Here’s an odd and almost forgotten fact: When black Memphians went

looking for an exemplar to become the city’s first African-African

chief executive in 1991, the year Herenton was finally selected,

Wharton, then serving as Shelby County public defender, was an also-ran

among the contenders, generally considered to be less viable than such

other hopefuls as Otis Higgs, a judge and veteran of mayoral races, and

Shep Wilbun, then a member of the City Council and one of the

organizers of the consensus movement.

He has worn well, however, and served well on behalf of such others

as Herenton, two of whose mayoral campaigns he managed, and statewide

candidates like Congressman Jim Cooper, a candidate for U.S. senator in

1994.

He already was considered a likely city leader when he was tapped by

various establishmentarians to run for county mayor in 2002, after

two-term Republican Jim Rout, seeing evidence of strengthened

Democratic demographics, decided to step down. A C, as almost everybody

called him, was black but had crossover written all over him. His very

blandness became a virtue. Yet, when needed, he could snap to and

answer a challenge — as when he warned Governor Phil Bredesen

last spring not to interdict any federal stimulus money headed for

Memphis, then charm Bredesen into not minding, with a joke about how the news

reports must have confused one mayor whose name ended with “-ton” with

another.

And Wharton has persistently fielded doubts about his overall

achievements as county mayor by pointing out the obvious — that

the powers of that job are as circumscribed as those of the one he now

seeks are expansive.

All his major opponents have criticized Wharton, with some justice,

as having dodged the debates. “Disrespectful” is the common term of

reproach. But the polls — his own, those of opponents, and those

taken by third-party sources — have been consistent. He doesn’t

just lead the field. He has virtually lapped the others, who trail him

by anywhere from 25 to 40 points, and he is candid enough to publicly

entertain hopes of winning an outright majority (though a plurality is

all he’ll need).

All this must be more than frustrating for the other mayor in

the race — Lowery, whose 60-plus days in office as the city’s

acting chief executive have been marked by a take-charge attitude and

by specific achievements: an edict allowing beer sales (and consequent

revenues) during University of Memphis games at the Liberty Bowl; his

announcement last week of red-light cameras at key intersections, a

means whereby policing powers could be conserved while advancing

detection of traffic offenses; a whirlwind of actions taken in the name

of transparency, culminating only this week with the release of

documents demonstrating that predecessor Herenton and the ex-mayor’s

CEO, Keith McGee, had claimed what seemed to be extravagant

compensation for unspent vacation time.

Lowery’s one stumble, his frustrated attempt to fire city attorney

Elbert Jefferson within minutes of being sworn in as mayor pro tem, had

the virtue of making Lowery look bold, like someone willing to take

chances, even if it meant running afoul of a council majority. Even if,

as Lowery’s detractors contend, Jefferson, a diabetic who has been on

sick leave for the last several weeks, is essentially a scapegoat for

the sins, real and imagined, of the Herenton administration, Lowery

succeeded almost instantly in becoming the anti-Willie of this year’s

mayor’s race. That was especially the case when the outgoing mayor

spent many of his last days in office singling out Lowery as an

antagonist who had to be stopped at all costs.

A councilman since his first election in 1991, the same year

Herenton became mayor, Lowery has positioned himself over the years as

a swing man on the council and, despite a certain brusqueness,

something of a conciliator.

Arguably, he has been the most effective of all participants in the

public forums, trotting out his motto, “What the others are promising,

I have already done,” and citing chapter and verse when asked about the

issues.

Surely he knows the odds against his succeeding this time around are

great. But, though he maintained after a downtown fund-raiser last week

that he had “no plans” for either 2010 or 2011, it is hard to see how

he could avoid trying again to get his hands on the reins.

That is, if the amiable and able A C Wharton wins as expected and

gives Lowery or anybody else a ghost of a chance to do so.