As I speak with the songwriter on the other end of the phone, it’s a bit difficult to believe that he’s from Lafayette, Louisiana: His accent is colored with the rounded tones of the English midlands. “I bounce back and forth between the U.S. and the U.K., as you can hear in my voice,” explains Richard Orange, chief guitarist and songwriter of the long lost Memphis band Zuider Zee. Though he now lives in Orange County, California, to these ears, it’s proof positive that he is an artist committed to growth and change, just as he was in the early 1970s, when his group was poised to take the world by storm.

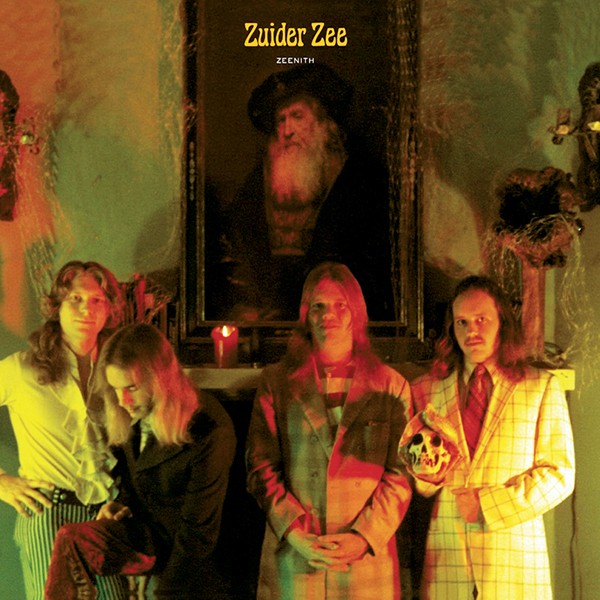

Memphis is already familiar with one tale of unsung power pop masters who cut marvelous tracks here in the early 1970s, only to languish in obscurity. So iconic is the Big Star story that it’s a shock to learn, with this year’s release of Zuider Zee’s Zeenith (Light in the Attic Records), that there was an even more obscure band woodshedding and recording in Memphis at the same time. Like Big Star, Zuider Zee (it rhymes with cider tea) was creating highly original music that holds up remarkably well today, but that is where all Big Star comparisons must end.

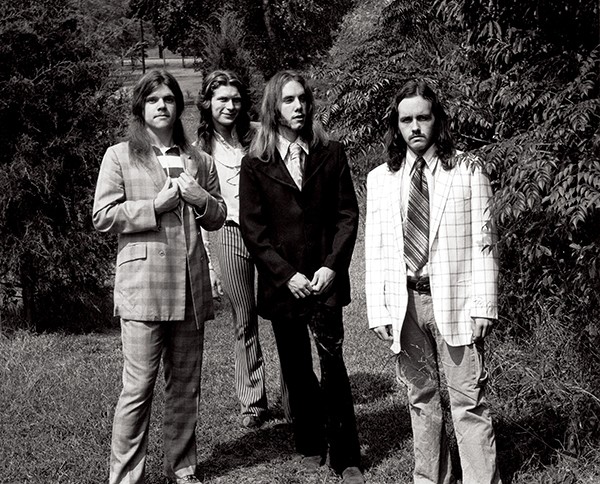

Gary Simon Bertrand

Gary Simon Bertrand

Zuider Zee (l-r, Richard Orange, Gary Simon Bertrand, John Bonar, Kim Foreman)

The greater adventurism in the songs, sounds, and arrangements of Zeenith are what make Zuider Zee unique, somehow redefining both power pop and prog rock simultaneously. Certainly, the band was drawing inspiration from the Beatles’ example of constant evolution, not to mention other sounds coming from across the pond. “What I liked at the time was mostly from England. I just adored King Crimson,” says Orange. Like those icons of prog, Zuider Zee was actively seeking novel sounds, textures, and harmonies (including a greater use of keyboards). But, unlike most prog, all innovations were in the service of concise songs that eschewed long flights of virtuosity.

Hearing the adventurism of Zuider Zee’s production and songcraft, it’s astounding that all of the tracks on Zeenith were previously unreleased, having been cut as demos at Memphis’ Trans Maximus International (TMI) studios. Those demos arose from still earlier demos the band cut in Louisiana under the name Thomas Edisun’s Electric Light Bulb Band [sic]. When Mississippi-based promoter and manager Leland Russell heard those, “he came and hunted me down in high school,” says Orange. Ultimately, Russell convinced them all to join him in a move to Memphis, where he set them up in a band house across from his new home on Raleigh LaGrange Road.

Once there, they relentlessly honed their material. “One thing I can say about that band is, I made them rehearse a lot,” recalls Orange. “We were very well rehearsed before we would go in and cut. So we could do a lot of those arrangements in real time.” The blend of turn-on-a-dime performances and imaginative production bells and whistles adds up to a kind of loose perfectionism in the tracks. While Orange’s voice has echoes of Paul McCartney or Freddie Mercury, things never get too glossy: The foibles give the record an earthy humanity that is sometimes missing from power pop.

Ultimately, Zuider Zee did get their big break with a major label, but that was years after these demos, and it was too little, too late. “The material on Zeenith wasn’t really an album. We just put that together for this release. Zuider Zee on Columbia Records in 1975 was a big deal. But they just completely dropped the ball. Probably no one’s heard of it because they never released a single. And in those days, radio wouldn’t play you unless you told them what to play.”

As if to refute the fickle logic of major labels like Columbia, the once-forgotten demos pre-dating Zuider Zee’s big break now add up to one of the best releases of 2018, or any year: a strange, inventive hybrid made by Louisiana boys stuck in the Bluff City, casting their eyes to England for a bit of transcendence.