The central motif of Wildlife, the brilliant new film by actor-turned-director Paul Dano, is an all-consuming wildfire. Released on the weekend when unreal images of burning Malibu and Paradise, California, flocked into our collective field of vision, the film has acquired an unexpected timeliness.

Or maybe it wasn’t so unexpected. As the Earth warms and rainfall becomes heavier but more sporadic, wildfire is becoming more common and more severe. This is a case of Dano and his partner, co-writer, and producer Zoe Kazan, making their own luck via deft choice of material — an adaptation of a 1990 novel by Jackson, Mississippi, native Richard Ford.

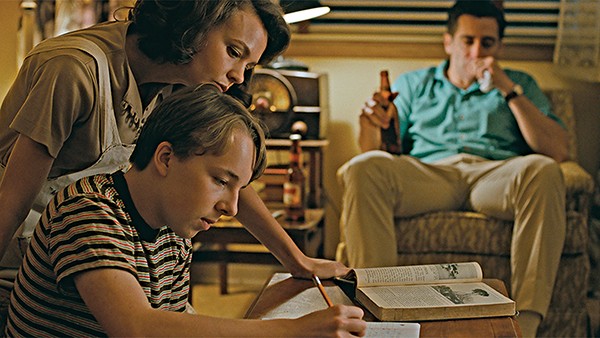

It’s 1960, and 14-year-old Joe (Ed Oxenbould) is trying to fit in and make friends at his new high school in Great Falls, Montana. His father Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal) is a golf pro, popular with the old rich guys at the country club. His mother Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) stays at home to keep the house like a good little wife.

Carey Mulligan, Ed Oxenbould, and Jake Gyllenhaal (left to right) star in Paul Dano’s tightly composed new drama,Wildlife.

Dano’s been acting since he was 10, and he’s been spectacular in films like Love & Mercy, where he nailed a difficult part as young Beach Boy Brian Wilson. So it’s natural that he would be an actor’s director. Wildlife is told from Joe’s point of view, but Dano pays equal attention and care to each of his lead trio of actors. In the beginning, it feels like Jerry’s story. Gyllenhaal’s epic, thrusting jawline embodies Eisenhower-era masculinity. He yucks it up with the privileged class on the links, even hustling them out of a few bucks here and there. But tellingly, he’s introduced cleaning the golf cleats of a cigarette-smoking banker, hunched over subserviently before capital.

When a bet comes back to bite him and he loses his job, Jerry starts to spiral into depression. A man without a job in America ought to be ashamed, even if it’s not his fault. Gyllenhaal’s performance is finely modulated — his mood in each brief scene is directly connected to what happened in the previous scene. Each rejection saps his will to go on just a little more.

As Jerry flounders, Jeanette starts to flourish. She gets a job teaching swimming lessons at the YMCA and enjoys getting out of the house and helping people be more self-sufficient. Even Joe gets a job before Jerry. He becomes a photographer’s assistant, and the portraits of weddings, graduations, and happy families become a poignant counterpoint to his own increasingly bleak home life.

The pressure of his own perceived failure becomes too much for Jerry, so it’s a relief to him when he finally lands a job on a firefighting crew that will require him to be in the Montana mountains until the winter snows put the fires out. The story’s focus shifts to Jeanette, who feels abandoned and betrayed by her husband leaving her to alone to raise a child, and the rest of the film belongs to Carey Mulligan. Joe watches his mother fall into a deep depression, then raise herself out of it by pursuing an affair with a rich man she met at the Y, played by a frighteningly greasy Bill Kamp.

Mulligan lets Jeanette’s self control slip away bit by bit. She is torn by financial worry, heartbreak, and social stigma, but also invigorated by the freedom of her bad behavior and the realization that she can be whomever she wants to be. Mulligan’s face gives you glimpses of the pitched battle inside her mind.

Dano not only has a deft hand with his actors, but also a great collaboration with cinematographer Diego García. As Joe’s formerly normal world closes in on him, García’s focal length narrows, leaving the character literally hemmed in by blurry uncertainty on the screen. The low light and muted palates give it a vintage 8mm home movie feel — assuming your old home movies were shot by Roger Deakins. Wyoming’s wide plains give way to soaring mountains in the distance, while in the foreground, desperate poor people huddle in desolate brick ranch houses. Wildlife is the inside story of a family burning down, but it is also a tale of toxic masculinity and capitalism’s spiritual toll. It’s a work that bridges the intimate and expansive with deceptive ease.