“The invention of Bob Dylan with his guitar belongs in its way to the same kind of tradition of something meant to be heard, as the songs of Homer.”

— Robert Fitzgerald

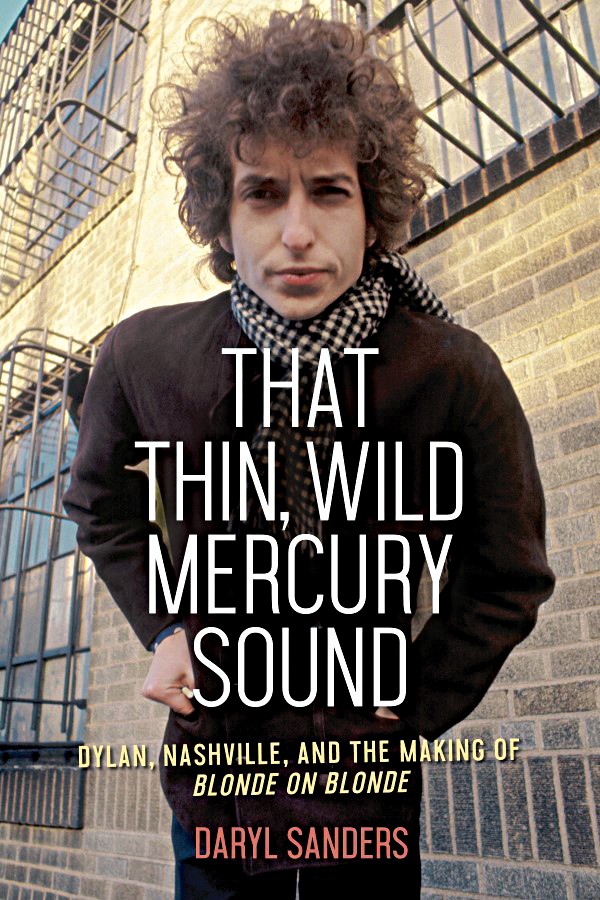

I’ve always loved making lists, ranking anything from movies to books to music to my friends. My ears perk up when I hear, “Name your Top 10 whatevers.” So, numerous times throughout my life, I’ve enthusiastically answered the question “What’s your favorite album?” Trouble is I’ve toggled back and forth numerous times between two albums: The Beatles’ Revolver and Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. To me, they seem the pillars of ’60s rock, my favorite genre in the known universe. Obviously, the book That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound: Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde by Daryl Sanders was right up my alley.

Sanders slowly leads up to the recording of that double album in Nashville, providing some colorful background: Dylan going electric, Dylan making Highway 61 Revisited, Dylan meeting and going on the road with the Hawks (who became The Band). It’s a pivotal period in Dylan’s life. He is about to change music forever. “I know my thing now,” Dylan says. “I know what it is. It’s hard to describe. I don’t know what to call it because I’ve never heard it before.” Sanders adds, “It would be another thirteen years before he found a description that worked — ‘that thin, wild mercury sound.'”

The title phrase refers to a music Dylan heard in his head, but which eluded him in the studio. He thought he found it with the Hawks. Instead, he was finally able to create the sound in his head on record when he went to Nashville and recorded this, his greatest album. Here’s the most common lineup with whom he found that once elusive sound: Producer: Bob Johnston. Nashville cats: Charlie McCoy (guitar and harmonica), Hargus Robbins (piano), Joe South (guitar), Henry Strzelecki (bass), and Kenneth Buttrey (drums). And Dylan brought with him Robbie Robertson (guitar) and Al Kooper (organ).

I’ve read a lot about Dylan, but he seems an inexhaustible subject. I learned a lot here. For instance, I didn’t know that Jerry Schatzberg, who later became a wonderful director (the Al Pacino film, Scarecrow), took the iconic cover shot. Dylan himself chose the blurry print, which delighted Schatzberg.

The meatiest part of the book concerns the actual recording of the album. Many of the sessions were done in the wee hours of the morning, which didn’t always please the professional Nashville cats, though they were, mostly, aware that they were part of something momentous. “According to studio records,” Sanders says, “it was 4 a.m. when the Nashville musicians finally got their introduction to the ‘Sad Eyed Lady’.” The reference is to “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” the epic song that took up the entire side four of the LP. “To me, this is the definitive version of what 4 a.m. sounds like,” Al Kooper said. Much of the wait was because Dylan was writing and polishing the lyrics as they went along. Often, he sat in a part of the studio cut off from the other musicians with just paper and a pen. Strzelecki said, “You know, this is going to be either the biggest album in the world, or it ain’t gonna do nothin.'”

Fortunately, the former part of his prediction is on the mark. After Blonde on Blonde was released and digested, it became one of the most influential records in rock music. Much about the recording, the songs, even the title, has become part of rock myth. Many believe the title is a reference to Edie Sedgwick, from Warhol’s factory, who dated Dylan briefly. Others suggested it referred to Brian Jones and Anita Pallenberg, or to Dylan’s high school girlfriend. Sanders adds, “Finally, there is also the fact that taken as an acronym, the title spells BOB.”

This fascinating, delicious book offers great insight into both the minutia of the recording process and Bob Dylan’s idiosyncratic, eccentric methods. For songwriters, this book may offer unlimited inspiration. For Dylan fans, it is a must.