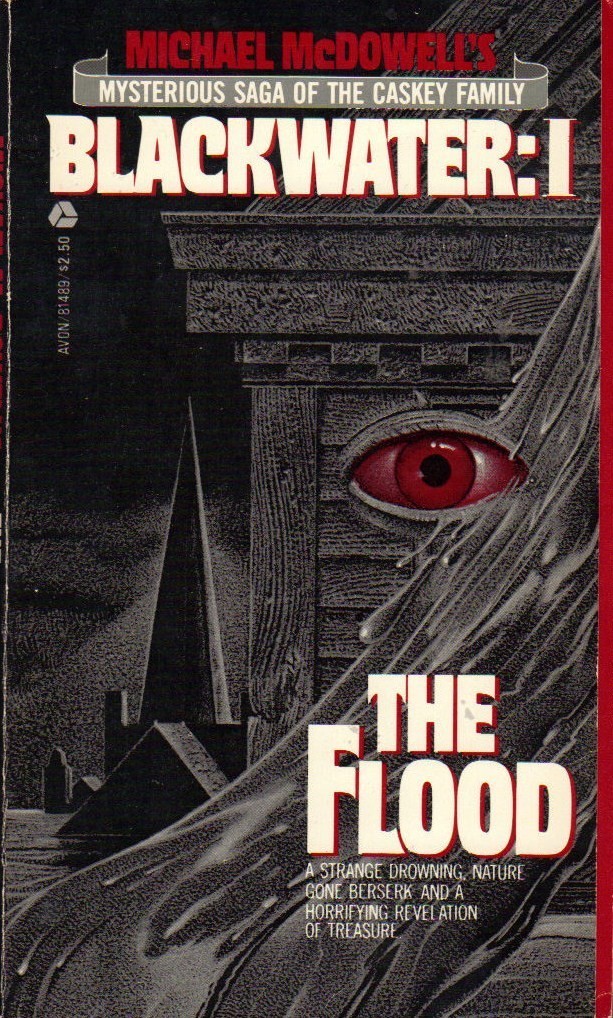

I recently finished Blackwater: The Complete Saga (Valancourt Books) by Michael McDowell, the prolific author who wrote the script for Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice.

Originally serialized in six volumes in 1983, I’m not sure how big a splash the Blackwater saga made on its initial release, but the darkly comic, Southern Gothic horror novel about family drama, societal norms, and a shapeshifting river monster still gets brought up on the kinds of message boards and subreddit threads where people talk about cult classic genre fiction.

The novel begins in 1912 in Perdido, Alabama, a little town nestled between the Perdido and Blackwater rivers, and records the lives of the Caskey family — beginning when Elinor, the aforementioned river monster, marries into the family. The fuel that propels the novel is the Caskeys’ ever-evolving family drama. And Blackwater offers no shortage where drama’s concerned; there’s plenty of porch-sitting infighting between the Caskeys themselves, not to mention the tension between the oddball family and the straight-laced Perdido townsfolk. Plus sometimes Elinor morphs back into an alligator-creature and eats someone.

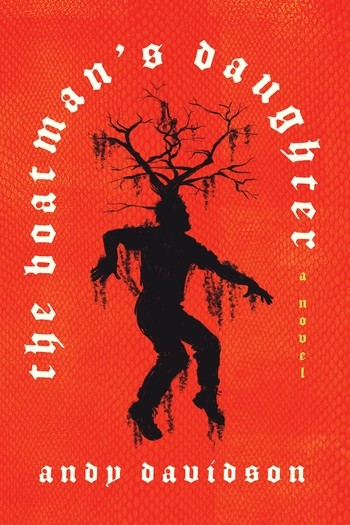

As much as I loved the 1983-era horror saga, I never thought I would get to write about it — that is, until I read The Boatman’s Daughter (MCD x FSG Originals), released earlier this February. I would wager that Andy Davidson, author of The Boatman’s Daughter, has probably read Blackwater. I had the good fortune of picking up an advance review copy after finishing McDowell’s six-volume saga, and I was struck by how much Davidson’s new novel reminded me of Blackwater — only bloodier, more muscular, and with far more menacing fangs.

Andy Davidson

Davidson will be in Memphis to discuss and sign The Boatman’s Daughter at Novel bookstore, Tuesday, March 3rd, at 6 p.m.

The Boatman’s Daughter recalls, at least in page-turner quality, the work of Joe Hill or Neil Gaiman (the British author’s more nightmarish fairy tales, anyway — think Sandman or Coraline, but, again, bloodier). The often poetic prose, though, and some of the motifs call to mind another Southern writer, one Cormac McCarthy. Still, the river creature, the book’s focus on ideas of family and outcasts, and the novel’s wrestling to understand that it’s not always what one does but how one looks that often leads society to label someone a monster — these all seem to hearken back to Blackwater.

All that isn’t to suggest that The Boatman’s Daughter is a collection of homages; it’s not. Instead it feels like an evolution. For all that Davidson’s novel seems to advance the work of earlier Southern authors, especially those mining the rich horror vein, it is also a delightfully original work. Its social commentary seems well-earned, too. Davidson can write about the South; he was born and raised in Arkansas, studied in Mississippi, and now lives in Georgia. And, as I mentioned earlier, it really seems as though he’s done his homework when it comes to the classics (and cult classics) in his chosen field.

The novel begins with a birth, a witch as a midwife, and an unnamed monster — all on the night of protagonist Miranda Crabtree’s father’s death — and it doesn’t slow down from there. Miranda works as a sort of swamp smuggler, ferrying contraband for Billy Cotton, an insane and murderous preacher. The cast of characters includes Miranda, the preacher, a corrupt sheriff, and the witch and a young boy, both under Miranda’s protection. And yes, someone looks like a river creature.

With such a weirdly wonderful cast of characters, a setting that centers around the river and the rotting Holy Days Church and Sabbath House, and themes of greed, violence, and family, Andy Davidson has crafted a creepily compelling Southern Gothic for our time. Even if I’m wrong and he hasn’t read Blackwater.

Andy Davidson discusses and signs The Boatman’s Daughter at Novel bookstore, Tuesday, March 3rd, at 6 p.m.