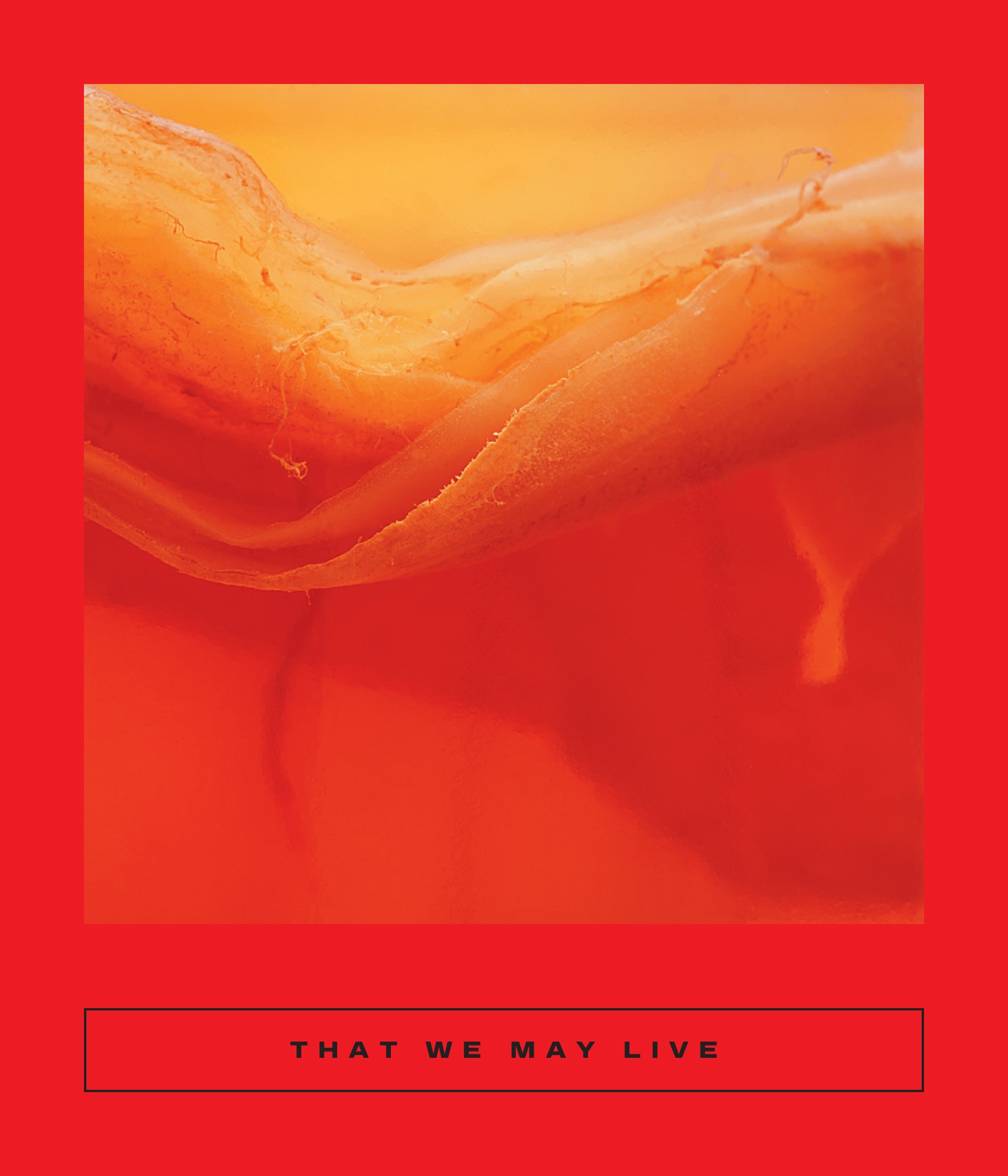

That We May Live

On March 10th, with the publication of That We May Live: Speculative Works of Chinese Fiction, Two Lines Press will debut the Calico Series, artfully reproduced collections of translated works of literature. The inaugural collection gathers seven short works of speculative Chinese fiction. Plastic surgery, surveillance, intoxicating fermented “tea,” and buildings that shuffle themselves around on their own accord fill the pages of the debut.

The collection begins, in Dorothy Tse’s “Sour Meat,” with a speeding train, squealing metal on metal, and a woman identified only as F starting awake, immediately establishing several of That We May Live’s motifs — the juxtaposition of human-made with natural phenomena, and the permeable barrier between the absurd or dreamlike and reality. Tse’s “Sour Meat,” translated by Natascha Bruce, reads like a fever dream of a fairy tale. That danger lurks in F’s future is certain, but the rules for how to skirt it are less clear. Why should a young woman’s trip to visit her grandmother be so fraught and frightening? What secret inner life is awakened at the taste of the grandmother’s fermented “tea”? And who are the strange sorority of women obsessed with — addicted to? — the mysterious beverage? The 26-page story deftly juggles dreamlike passages with hints of generational trauma, giving just the barest hints, wafting like steam from potent tea.

Dorothy Tse (courtesy Two Lines Press)

Dorothy Tse (courtesy Two Lines Press)

Enoch Tam’s work is represented twice, and his first offering, “Auntie Han’s Modern Life,” deals with issues of urbanization, displacement, and the uneven symbiosis between modern/urban and traditional/rural areas. “Auntie Han knew the houses had been in low spirits for a while,” Tam writes. “Some were even depressed enough that they stopped moving altogether. The others did everything they could to remind their moribund companions of all the times they’d worked together to thwart the humans and how satisfying it had felt to be constantly mobile. But the sad, silent houses remained sad and silent.”

That the stories in That We May Live resonate with the gravity of fairy tales and mythology is a credit to all parties involved — the writers, translators, and editors all did excellent work. Every short story should strive for high stakes and economical, poetic use of language, but not every short story collection hits that mark with the consistency and accuracy of the selections represented here. Each offering adds a layer, deepening the resonance of the themes explored in the collection.

Natascha Bruce (courtesy Two Lines Press)

Natascha Bruce (courtesy Two Lines Press)

“After the elephant vanished, my life fell into chaos,” writes Hong Kong-born Chan Chi Wa, translated by Audrey Heijins, in “The Elephant.” In a sentence that could be applied to any story in the collection, Wa continues, “I wondered if I was hallucinating — the scene in front of me must have been an illusion, a misconception, a mirage in broad daylight.” A mirage in broad daylight, indeed, is often what the reader is left contemplating. But these mirages tempt the reader onward — searching for meaning or just another beautiful, dangerous, dreamlike image.

Enoch Tam (courtesy Two Lines Press)

Enoch Tam (courtesy Two Lines Press)

“It was the garden-keepers who ruined the mushrooms,” Tam writes in his second contribution to That We May Live, a story that also focuses on geography and gentrification. “When the residents opened their front doors the morning after the storm, they’d find their street completely transformed, a seafood restaurant suddenly where a convenience store used to be, a stationary store now replaced by a comic book shop.” Though, if anything, “The Mushroom Houses Proliferated in District M” is even more bizarre than “Auntie Han’s Modern Life.” Tam’s ability to transform a short story about gentrification into a hallucinogenic fable populated by house-sized mushrooms serves to prove his masterful handling of the craft. Tam has earned his double-inclusion in That We May Live.