Poole

Poole

Poole, a first-generation college student, won’t get a chance to walk across the stage this spring.

When Brianna Poole joined Lambda Theta Alpha during her freshman year in college, her sorority sisters nicknamed her “resilient” — and resilient she has been.

Because of the COVID-19 outbreak, there will be no pomp and circumstance for Poole, a senior at the University of Memphis, to march to next month, but nevertheless, she will be the first one in her biological family to graduate college. She is already the first to graduate high school.

Poole, who is majoring in social work, like college students around the country, is finishing up her classes virtually. She said she feels like the school year was abruptly cut short after a two-week spring break.

“There was no closure at all with my professors or with my job on campus,” she said. “I didn’t really have a chance to say goodbye or see you later. It was just so abrupt. It kind of reminded me of when my dad died, but not as extreme.”

Poole’s dad passed away from a sudden, massive heart attack just a couple of months before she started her freshman year of college. His death — and his life — is what inspired Poole to go to college and to complete college.

Her dad, a family friend, adopted her when she was 12 years old. Poole said her decision to pursue social work is largely due to her experience in the system and with adoption. She plans to use her degree to help facilitate adoptions in the future.

Poole is a first generation Mexican-American. Born when her biological mom was just 17, Poole grew up in DeSoto County. Her biological dad was deported to Mexico before she was born.

[pullquote-1]

She says her mom “didn’t really know how to cope with everything,” which led her to start abusing alcohol and drugs when Poole was young, like many family members before her. Poole said she wanted to go to college to break the cycle.

“Before I got adopted, I didn’t like the way I was growing up, living in poverty,” Poole said. “I didn’t like living in a crime-ridden area. We didn’t have a car. I didn’t eat sometimes. My mother left days on end to go get drugs. I just didn’t want that anymore. People told me to stay in school and I wouldn’t have to live like this anymore.”

She said she first realized how important getting an education was in high school: “Education is, without a doubt, 100 percent the way out of situations like that.”

Her adoptive dad was a truck driver and didn’t have a college degree.“He had a blue collar job and he hated it and he would tell me, ‘Make sure you finish college so you don’t have to waste your day away working as hard as I do’”

Poole was the first person in her biological family to complete the 11th grade and the first in her adoptive family to go to college.

“It’s what my dad always wanted me to do,” she said. “He pushed me to further my education. He always told me to stay in school. I was just hoping my dad could see it and be there with me when I graduated. Even though I know he wasn’t going to be there physically, he would have been there in a way.”

Poole

Poole

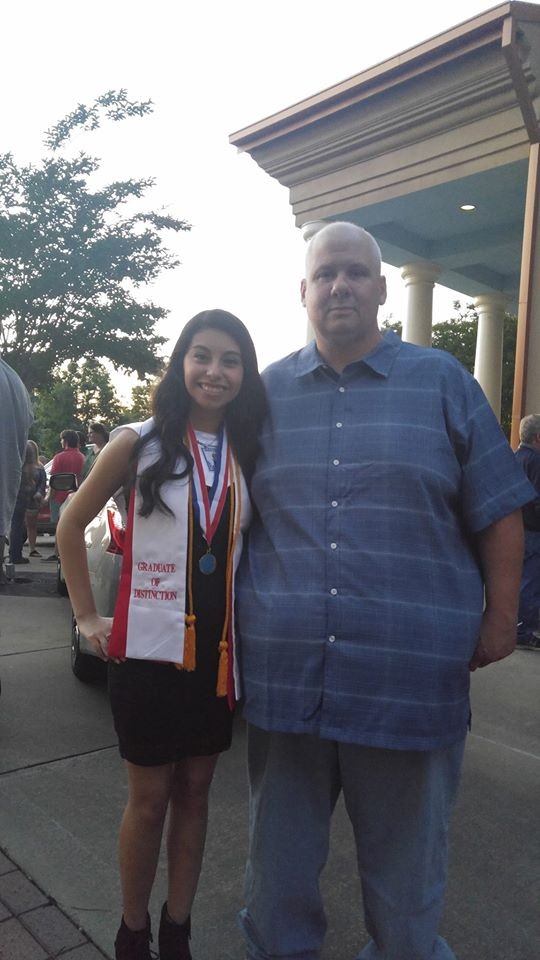

Poole and her dad on the day she graduated high school

As a first-generation student and a first-generation Mexican American, Poole said graduation “was a big deal” for her.

“Having a physical graduation, getting my name called, walking across the stage, and having people cheer for me was something I was really looking forward to,” she said. “I guess I just wanted that moment to know that I made it, that I did it.”

For Poole, graduation represents a broken cycle — of poverty, drug use, and a lack of education.

“I’m breaking the cycle and changing the assumption that Hispanics aren’t educated,” she said. “I’m also breaking the cycle of drug and alcohol use in my family. I’m the first one to get anywhere. Now, hopefully my kids will go to college. I’m the one who is making a change in my family.”

Poole said she did not want to be another statistic, saying that most people who are adopted or go through foster care don’t complete college.

“I felt like I had a lot of things stacked against me — first generation, Mexican American, and a death right before college,” Poole said. “I just wanted to be resilient, not a statistic.”

[pullquote-2]

Poole said she was looking forward to getting her cap and gown and decorating her cap. She planned to list the very statistics that she did not want to be counted in on her cap — statistics related to those who are adopted, experience a death, have drug use in the family, and first-generation Mexican Americans. On the inside of her cap, she was going to draw a palm tree, a symbol her sorority adopted because of the tree’s ability to bend, but hardly ever break.

Poole also had a very specific photo in mind that she looked forward to taking donned in her cap and gown. She was going to hold a framed picture of her and her dad. The picture was taken the day she accepted a college scholarship.

“It would have just shown the transition in growth,” she said. “Getting that scholarship was a big deal and he was there with me. Now, I’ll have another piece of paper, a diploma, that means so much. He’s not here, but he was a part of this journey and that’s what the photo would have symbolized.”

Without a traditional graduation ceremony to look forward to, Poole is looking toward her future, planning her next endeavor. She is applying to get her master’s degree in social work at the U of M next year. It’s a one-year program and at the end of it she hopes to be able to participate in a real graduation ceremony to celebrate both accomplishments.

“I don’t think people have to be their circumstances,” Poole said of her journey thus far. “I think what makes a person is how they respond to their circumstances. I chose to be resilient.”