As the Memphis Redbirds prepare to defend their Pacific Coast League championship — Game 1 of the finals against the Tacoma Rainiers is Tuesday night at AutoZone Park — it’s worth noting the 10th anniversary this week of one of the greatest moments in Memphis sports history.

It was the definitive “grandkids moment” in the 30-plus years of my life as a baseball fan. You know the kind: You look at a fellow fan after it happens and shout, “I’m gonna tell my grandkids I was here!”

September 15, 2000. AutoZone Park. Game 4 of the best-of-five Pacific Coast League Championship Series between the Memphis Redbirds and the Salt Lake Buzz (top affiliate at the time of the Minnesota Twins). The Redbirds led the series two games to one, and had led Game 4 until a collision of players under a pop fly in the top of the ninth inning allowed two runs to score for Salt Lake, tying the game at three and sending it to extra innings.

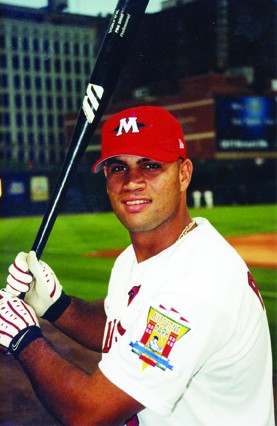

With two outs in the bottom of the 13th, 20-year-old Albert Pujols strode to the plate, playing only his 12th game at the Triple-A level. Pujols had already made a name for himself within the Cardinal system, earning Player of the Year honors in the Class-A Midwest League, where he’d hit .324 with 17 homers and 84 RBIs in 109 games for Peoria. He had been promoted two weeks earlier when the Redbirds lost their star leftfielder, Ernie Young (and his team-leading 35 homers and 98 RBIs) to the U.S. Olympic team in Sydney. The p.a. announcer at AutoZone Park — introducing the young star to Memphis fans for the first time — called him “Alberto” Pujols.

Wearing the number 6 on his back — a sacred number to Cardinal fans who worship at the altar of Stan Musial — Pujols stood in against Salt Lake’s David Hooten and worked the count to two balls and two strikes. Then he changed Memphis baseball history. Pujols connected on the next pitch, perhaps a little later than he intended but on the sweet spot of his bat, arms fully extended. The line drive sailed down the rightfield line and started hooking toward foul territory, only to sneak just inside the foul pole. Game-winning, championship-winning, name-making walk-off home run by Albert Pujols. Redbirds radio voice Tom Stocker screamed into his microphone, “Touch every base, Albert! Touch every base!!”

Thus ended the inaugural season at AutoZone Park, reminiscent of Mazeroski in ’60, Carter in ’93. A crowd of 11,703 witnessed the first Memphis baseball championship in 10 years, and the first ever at the Triple-A level. But we really had no idea — yet — what we’d seen.

Instead of being a feature attraction in Memphis the next season, Pujols made the 2001 Cardinal team out of spring training, and by the All-Star break (he was named to the National League squad) Pujols had turned Ray Lankford, Jim Edmonds, and even Mark McGwire into supporting players for St. Louis. With Pujols on his way to one of the finest rookie campaigns in baseball history — .329 batting average, 37 home runs, 130 RBIs — I began thinking that those 11,703 fans the previous September had seen the baseball equivalent of Marlon Brando strutting the stage of a Des Moines community theatre.

Ten years later, Pujols has three National League MVP trophies on his mantel. Barring an epic late-season slump at the plate, Pujols will this year become the first player in baseball history to reel off ten straight seasons with a .300 batting average, 30 home runs, and 100 RBIs. Babe Ruth didn’t do it. Lou Gehrig didn’t do it. Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Musial himself . . . none of them did it. The argument could be made that Albert Pujols is a Hall of Famer before his 31st birthday.

My two daughters saw their first Pujols home run at AutoZone Park in 2004, during a Cardinals preseason exhibition game. They saw him hit another at the new Busch Stadium in St. Louis, during the championship season of 2006. But neither of those shots — however memorable — has a seat painted bright red to commemorate where the ball landed. Just inside the rightfield foul pole at AutoZone Park, standing out against the thousands of green seats that fill the rest of the ballpark, is just such a marker. My daughters have sat in that seat. Perhaps someday their children will ask why it’s painted red, and they’ll be told stories of the great Pujols, of all the records he’s broken and championships he’s won. But rest assured, if Grampa is there, the conversation will begin with September 15, 2000.