What does the American Athletic Conference know about pandemic football that the Big Ten doesn’t? Or to rephrase for a more worrisome question, what does the Big Ten know about the coronavirus and football that the AAC doesn’t?

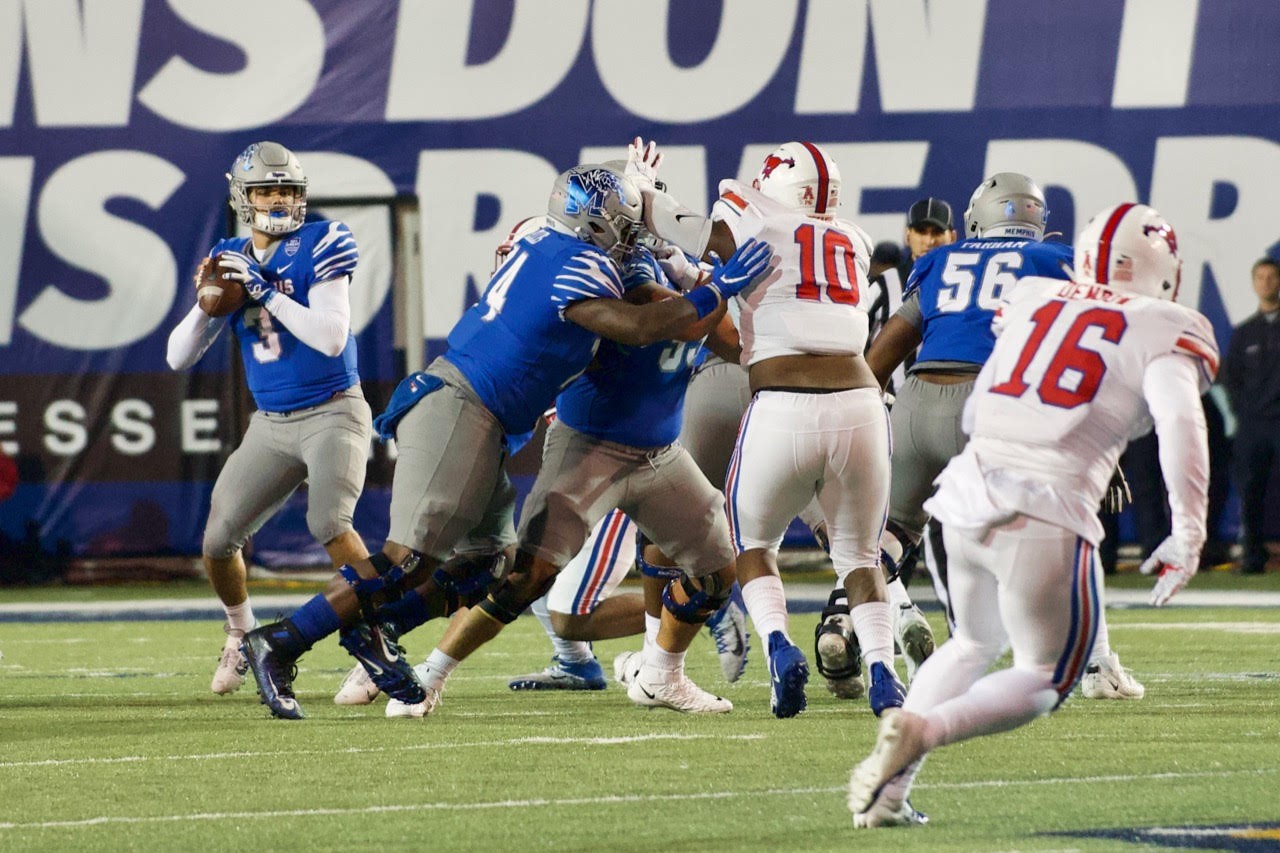

As spectator sports reawaken — with major restrictions — under the current pandemic conditions, two “Power 5” college football conferences announced last week that they will not be fielding football teams this fall. In addition to the Big Ten — no Michigan! no Ohio State! no Rutgers! — the Pac 12 will keep its helmets and shoulder pads in closets at least until the spring when, maybe, we’ll have more clarity on how mankind emerges from this health crisis. Two “Group of Five” leagues — the Mid-American Conference and the Mountain West Conference — have also cancelled play this fall. But as of now, the Memphis Tigers and ten football-playing AAC brethren are preparing to clash on the gridiron next month. What are we to make of the differing approaches to the same contagion?

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

When I ponder what football in 2020 might look like, it’s not the empty stands (a given) that captures my mind’s eye. It’s the sidelines. During an FBS college football game, more than 100 people — players, staff, trainers — stand along each sideline, typically over a 60-yard strip (between the 20-yard lines). It’s the precise opposite of social distancing. It’s social packing. Will every player and coach on every sideline this fall wear a protective mask? How will trainers safely address a twisted knee or turned ankle? When a player is unable to leave the field under his own power, how many people can safely attend to his care and transportation?

These are superfluous questions, of course, when it comes to football. On every snap in every game — more than 100 times per game — at least five and often as many as 11 players on one team each collide with a player on the other. It’s the kind of human behavior a catchy virus dreams about. Can such a sport be played while, at the same time, keeping that catchy virus outside the stadium?

Here’s the word that will most come into play in the weeks and months ahead, especially if football teams do, in fact, kick off near Labor Day: myocarditis. The condition’s quick definition (via Wikipedia): “inflammation of the heart muscle, also known as inflammatory cardiomyopathy.” Links have been established between COVID-19 infection and myocarditis, and specifically in the bodies of athletes. A sport already afflicted with criticism for the damage it does to the human brain is now measuring if it can be played without damaging another rather vital organ in the human body. Were I a 20-year-old athlete, my sense of immortality might supersede concerns about my gray matter. But damage to my heart? I suppose football can be played after one gets one’s “bell rung” a few times. If the heart isn’t operating properly, a lot more than football will be lost.

The coronavirus is a worldwide villain (thus use of the word pandemic). It knows no region, certainly no conference affiliation. Which makes a look at the football conferences ready to play this fall somewhat troubling: they all include schools in the southern United States. Do the powers-that-be running the SEC, ACC, Big 12, AAC, Sun Belt, and Conference USA have a handle on controlling the coronavirus that the leagues up north and out west haven’t discovered? We all love (or hate) the correlation between the South and football, how you can’t live with (or in) one without loving (or adopting) the other. But at what cost during a pandemic?

In late July, I asked Memphis quarterback Brady White — a California native and a PhD. candidate, mind you — if he was prepared for an interruption or cancellation of his final season as a Tiger. “What we’re doing now is different from everything we’ve done in the past,” he said. “We recognize that, and we accept it. We know the possibilities, but we’re preparing for a full season. We’re preparing to be playing September 5th at the Liberty Bowl. You’d rather over-prepare and be ready to play than sit on your hands and then you’re behind the eight ball [when games are played]. I love the way we’re doing it. The biggest thing for football players in general is getting your mindset to ‘go’ mode.”

We’ll know soon enough if the AAC and other southern football conferences choose the “go” mode for 2020. As college students gather on campuses where masks are required everywhere except dorm rooms, college football players will — or won’t — take the field with even more at risk than their knees and thinking caps. Those deciding when (or if) to take such a risk must get this right, as there won’t be a second chance.