Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

Ninth District Congressman Steve Cohen

U.S. Rep. Steve Cohen (D-Memphis) urged president Joe Biden Monday to rescind a federal permit for the Byhalia Connection pipeline ahead of a possible Tuesday meeting by the Memphis City Council to oppose it.

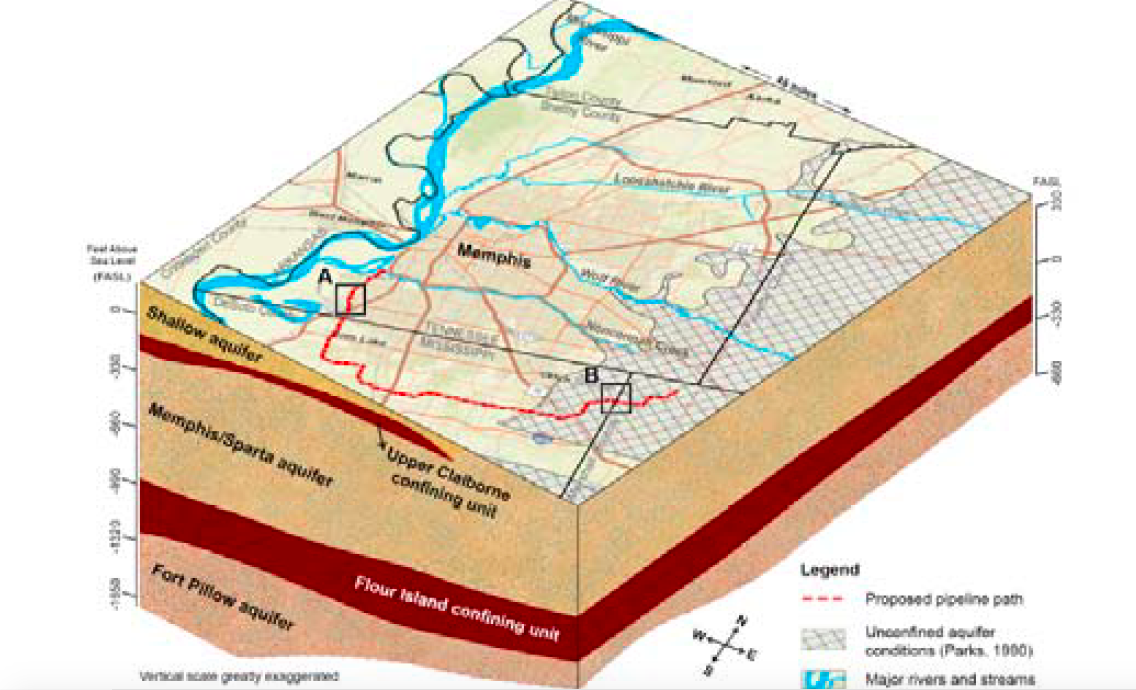

The pipeline project won approval from two U.S. Army Corps of Engineers offices (Memphis and Vicksburg) nearly two weeks ago to build a 49-mille crude-oil line from Memphis to Marshall County, Mississippi.

The project has faced major opposition from environmental groups, as the line would be built across a well field that connects to the Memphis Sand Aquifer, the source of Memphis’ famously pure drinking water. The project has broader opposition from groups who say the line would be built through predominantly Black neighborhoods. Cohen pointed at both of these arguments in his letter to the Biden Administration.

“The proposed Byhalia Pipeline would impose yet another burden on Black neighborhoods in southwest Memphis that have, for decades, unfairly shouldered the pollution burdens of an oil refiner, and coal and gas-fired power plants,” Cohen wrote. ”If built, the pipeline will cross a municipal well field that supplies drinking water to local Black residents in Memphis.”

[pdf-3]

For its part, Byhalia Connection, a joint venture of Valero and Plains All American Pipeline, said it picked the route for the pipeline with considerations for endangered species, neighborhood development, parks, landmarks, and cultural and historic sites, according to company spokeswoman Katie Martin. The company looked at Nonconnah Creek, flood control structures, T.O. Fuller State Park, and more. It also chose to run its line across mostly vacant properties; Martin noted that 62 of the 67 pieces of property on the route are vacant.

The company also worked with the Centers for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER) at the University of Memphis to learn about the aquifer. The company determined that the ”drinking-water portion of the aquifer is far below where our pipeline will be, which is 3-4-feet underground.

“So, we really are trying to thread the needle and find the way to cause the least amount of disruption and the least amount of concern for the community as possible,” Martin said.

Along with his letter, Cohen posted a copy of a letter from Corps of Engineers District Commander Col. Zachary Miller. In the letter, Miller responded to Cohen’s many questions regarding the project and why they approved it.

[pdf-1]

For one, the Corps said it does not have jurisdiction over groundwater issues. Its permit process is limited to wetlands or streams, and the project presents “no projected impacts” to either, the letter reads.

Ground water considerations are the purview of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC), which granted a state permit for the project more than a month ago. An oil spill from the pipeline “is not reasonably likely” to contaminate the aquifer, Miller said.

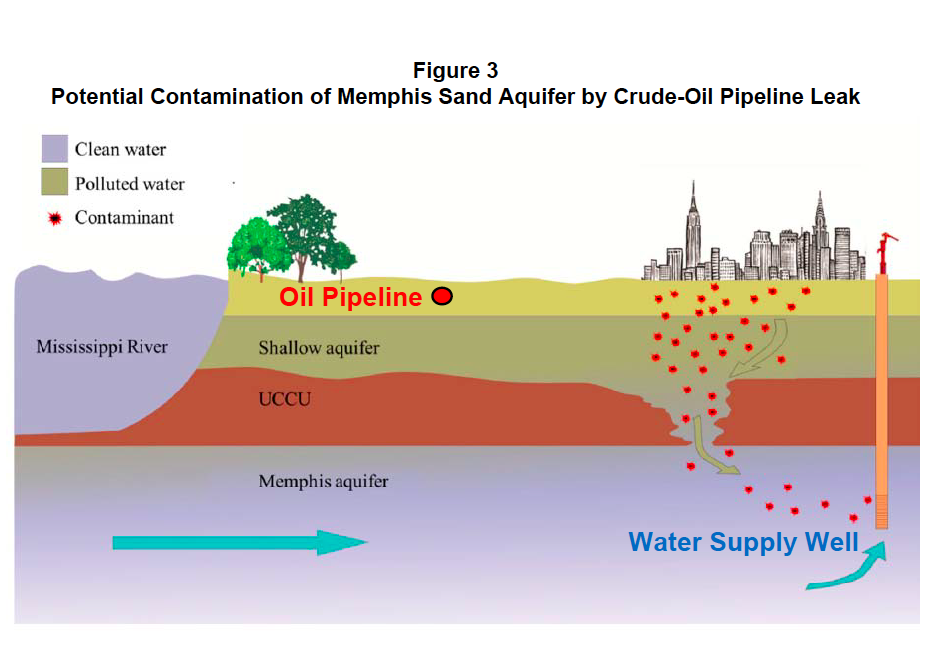

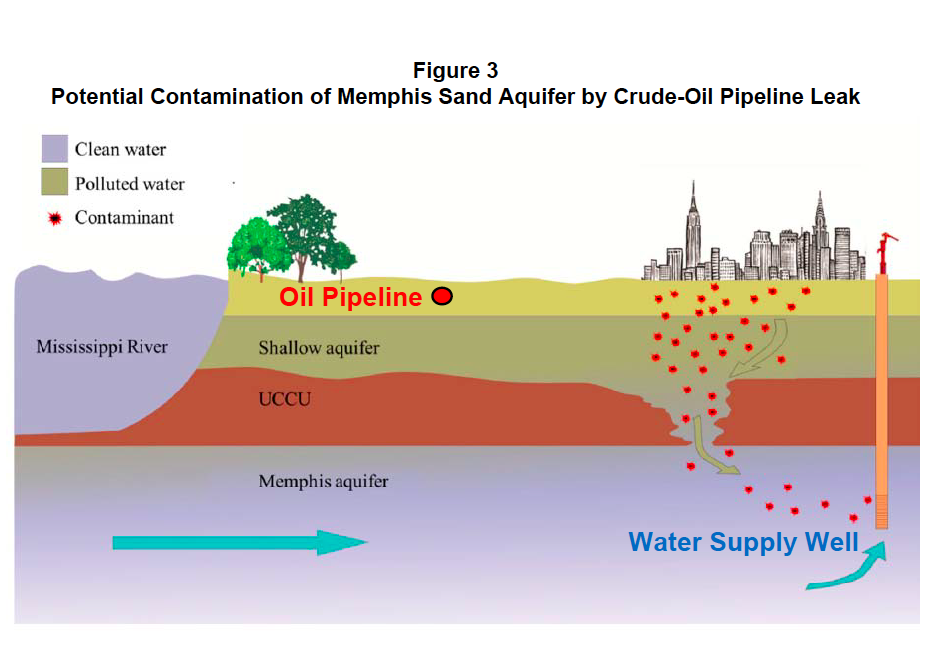

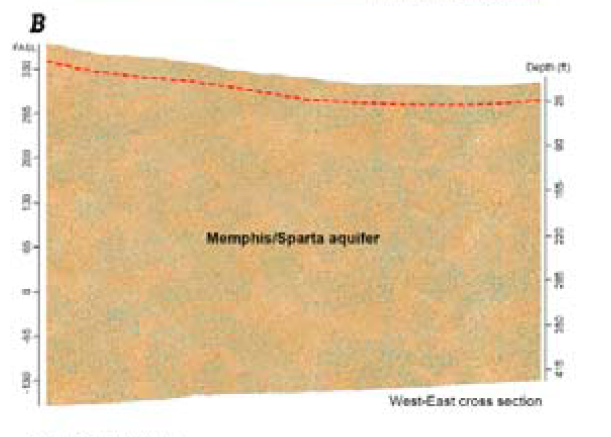

“To the extent your question involves concerns with a spill causing contamination of the aquifer, the information received from members of the public on this point indicate that contamination of the aquifer is not reasonably likely to occur due to local geography as well as distance between the pipeline and the Memphis Sand Aquifer,” reads Miller’s letter. “Aside from the terminus in Eastern Mississippi, the pipeline will be located 3 feet-10 feet underground, well over 100 feet above the drinking water aquifer, and separated by a confining clay layer.”

Jim Kovarik, executive director of Protect Our Aquifer, says the state has a bias for Middle and East Tennessee in this permit process. Most of the drinking water from those areas come from ground water.

“There’s never been protections written into the law specifically for West Tennessee, which enjoys a sand aquifer and it’s a different kind of a beast,” Kovarik said. “It’s all coming to light as these permitting agencies do their thing. They say, ‘you know, the [Memphis Sand Aquifer] is not our concern. It’s several hundred feet below where this is happening. These are only surface intrusions.’ And, you know, the subtext is ’we don’t really care.’”

Th Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) conducted a hydrology report to review the pipeline’s potential threat to the aquifer. That report notes that the Memphis Sand Aquifer is hydraulically connected to other, more shallow aquifers above it through holes in the clay layers. Depending on where a potential leak could happen, crude oil from the pipeline could reach the Memphis Sand “in a matter of years rather than the decades usually associated with the amount of time it takes water to travel through the ground to the city’s drinking water source,” said George Nolan, a senior attorney at SELC.

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

”Crude oil spills are difficult if not impossible to completely clean up, particularly when they impact groundwater,” Nolan said. “Crude oil contains known carcinogens and hazardous chemicals, such as benzene, and once crude oil reaches groundwater, the resulting contamination plume in the affected aquifer can be very persistent.

“When spilled underground, crude oil can dissolve into hazardous particles that spread throughout the water. In fact, one pound of crude oil can contaminate 25,000,000 gallons of groundwater, according to the report.”

However, company spokeswoman Martin said All Plains moved 90 billion gallons of oil last year. The one leak it had last year was from a third party company that hit one of their lines “that had nothing to do with us or our construction.”

Martin has also said the Byhalia Connection line here would come with a number of safeguards, including leak detection system for constant monitoring of line pressure and weekly monitoring of the line from the sky.

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

On the question of environmental justice — whether or not the pipeline would disproportionately affect Black communities — the project checked one box but not another. The ”socioeconomics and demographics” of the affected area did trigger federal review of the project on environmental justice concerns.

But the project itself would not negatively affect those communities, the letter said. The “activities authorized by this permit will not exceed de minimis levels of direct emissions,” or emissions too low to merit consideration.

While many of the properties along the proposed route are vacant, some aren’t. Some of the property owners there have sold easements to Byhalia Pipeline. Some didn’t, and some of those are under threat of having their land claimed anyway though eminent domain.

Scottie Fitzgerald said during an anti-pipeline rally recently that she’s owned property in South Memphis since 1982. She said she was confused as to how the company could claim property along the pipeline route with eminent domain. The method is to take property for something that will “propel Memphis,” or benefit the city like sidewalks.

She said she told the company no. She told them not to survey her land and she put a ”no trespassing” sign in her yard.

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), University of Memphis

“My answer was no,” Fitzgerald told those on the rally’s Zoom call. “Now, you’re just going to strong-arm me and bull me and take it? That’s just not legal. That’s not right. That’s not ethical. It’s not moral. It’s wrong.”

“No crude oil pipelines built near an earthquake zone atop an aquifer that supplies a predominantly Black community drinking water can be safe,” said Justin Pearson, organizer of Memphis Community Against the Pipeline (MCAP) group, which organized the rally against the project. “This fast-track permit removes community voices and doesn’t protect our most invaluable resource — our water — from the dangers of this pipeline. It’s time to stop the Byhalia Pipeline and end this environmentally racist pipeline project.”

Cohen appealed to Biden’s promised actions on environmental issues, especially climate change, to request the permit be rescinded.

“As you take immediate action to address the climate crisis, I write to ask your administration to direct the Army Corps of Engineers to rescind its recent verification of the use of the Nationwide Permit 12 (NWP 12) for the proposed Byhalia crude-oil pipeline that would threaten the drinking water and disrupt the property rights of predominantly Black neighborhoods in my district,” Cohen wrote.

Scott Banbury, conservation program coordinator of the Tennessee Chapter of the Sierra Club, said “the Biden administration has pledged to address environmental racism, and revoking this permit would show action on that promise.”

City of Memphis

City of Memphis

Edmund Ford

“The Corps ignored the harm that this dangerous pipeline could cause to drinking water and it failed to consider how that harm will affect the already environmentally burdened communities it will pass through in Southwest Memphis,” Banbury wrote. “We can’t let this stand unchallenged.”

Cohen’s ask comes as many opponents are tying their hopes to stop the pipeline on local action, instead of federal.

Locally, Memphis City Council members Dr. Jeff Warren and Edmund Ford have co-sponsored a resolution to

Jeff Warren

oppose the pipeline. The measure had one hearing a month ago. Its second review was slated for last week, but was stymied by winter weather. The council will take up the opposition resolution during its meeting scheduled for Tuesday.

Resolutions are usually non-binding, and are mostly a way for council members to officially capture an opinion on a matter. However, the one before the council asks Memphis Light, Gas and Water to not cooperate with the Byhalia Connection company.