On March 13, 2020, Jamie Harmon took a photo of his friends Ryan Azada and Maria Applegate peering from behind a screen door. When he posted the photo to Instagram, he asked if others would be interested in participating in this new project of documenting families inside their homes from the outside looking in. It was the beginning of the lockdown period of the pandemic, when naiveté told us that this coronavirus would pass soon enough, that a new hobby, project, or binge-watch would keep us sane in the meantime.

“I was thinking it was only going to be a two-week project,” Harmon says. “Over that two weeks, I had over a hundred people texting me and messaging me [to sign up].” Soon enough, word of the project spread in newspapers and even on CBS Sunday Morning. “I started getting more diverse kinds of people and locations once it left social media.”

Over the two-and-a-half-month course of this project, Harmon photographed more than 1,200 residents at over 800 homes across the Greater Memphis area, as far out as Millington, Mumford, and even Hernando. Each participant received a weblink with edited photos that they could download, free of charge.

“This was just something we were doing because we had nothing else to do and it felt like something good to do,” Harmon says. “A lot of people were dealing with stuff, and I had one singular focus and that made it easier for me because I was doing what I loved to do anyway.”

Each shoot took around 15 minutes, so Harmon could visit as many homes as possible in a day. During the sessions, Harmon, geared with only one light and one camera, shot three locations at every house, letting the family pick one of the spots while he chose the others. With the photographer outside and his subjects inside their homes, the two parties communicated via phone. “Everything’s a collaboration,” Harmon says. “I wanted the families to be involved; I wanted the kids to have ideas. … A lot of the times the parents were like, ‘I don’t have a creative bone in my body; I’ll just do whatever you want,’ and then you start telling them what to do and then they start having ideas and they chime in.

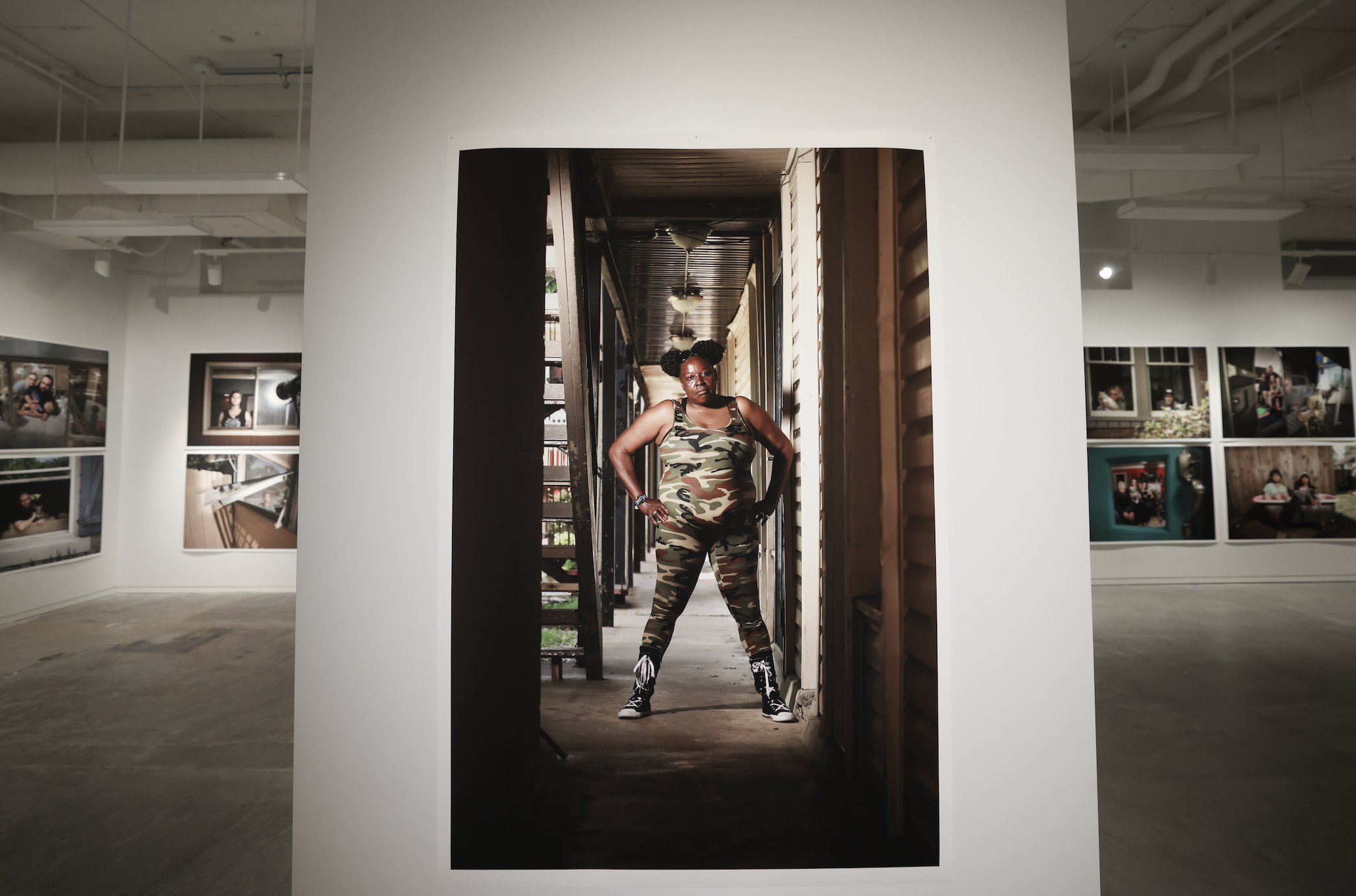

“Everybody was excited that something was happening,” Harmon continues. “It was something to break up the day.” Despite this excitement spurred in these 15 minutes, Harmon would make sure to have his subjects try on a stoic face for at least a few of the photos — the photos that would later make up his current exhibition.

“It’s almost a joke because when somebody tells you to have no expression, generally you start laughing,” Harmon says. “So even though it looks pretty somber, it’s a very different experience.” Yet these opposing emotions that wavered between concern and relief, boredom and excitement, reflected the rollercoaster of quarantine, for even on days when we celebrated birthdays or cheered on virtual graduation ceremonies, Harmon says, “Definitely in the middle of the night, I think we all felt a little panicked.”

But as much as this project was a comfort for Harmon, the project was also a comfort to its participants, who felt like they were a part of something larger than themselves, a part of a bigger picture. Harmon says, “I think a lot of the people who signed up saw it as something I didn’t notice at the time, which is two years later there’s an exhibit up.”

The exhibit will remain on display at Crosstown Arts until April 10th, with a closing reception on April 10th at 3-5 p.m. A book of the photos seen in the exhibition is available for pre-order at memphisquarantine.com.