I made my first pronouncement on the art scene around age 18. It was during my first formal sit-down dinner in the late ’60s or early ’70s at the home of the late philanthropist Clarence Day. I actually had to ask a young woman next to me which spoon to use for something or other during dinner. Just like in the movies.

As I recall, we moved to a room with expensive oil paintings and lots of books following dinner and we were sipping Grand Marnier out of snifters when the question was asked, “Who is your favorite artist?”

I said, “Doris Lee. She’s a contemporary artist.” Emphasis on “contemporary” as if to prove I knew what I was talking about. I told them her painting “Arbor Day” was my favorite painting. I didn’t notice any rolling eyes, but “Doris Lee” probably wasn’t up there with Cezanne or Monet or whoever was on their lists.

Decades later, “Arbor Day” is still my all-time favorite painting. I first saw it in a book we had at home when I was little. Looking at it again I notice how a lot of the subjects in that painting came true in my life. It’s set in the country. It reflects my love of gardening. Even the two horses are the same colors as mine.

So when I noticed a listing in the Memphis Flyer announcing a Lee exhibit, “Simple Pleasures: The Art of Doris Lee,” at Dixon Gallery and Gardens, I was ecstatic. I couldn’t wait to see it. I’d only seen maybe two other paintings by Lee over the years.

On a beautiful 70-degree day after the holidays I made a visit to Dixon to see the show.

It’s fabulous.

The exhibit, closing January 15th, is a delight. With the temperatures on the mild side and the throng of daffodils sprouting in the the Dixon garden, now is a great time to take in this show.

Sadly, “Arbor Day” isn’t in the show because it couldn’t be loaned, says Melissa Wolfe, who, along with Barbara Jones, curated “Simple Pleasures.” But there is a depiction of the painting in a Maxwell House coffee ad in the exhibit.

Wolfe, who is curator of American Art at the St. Louis Art Museum, sums up Lee’s work with one word. “I really connect it with joy,” she says.

And Lee’s work is accessible, Wolfe says, “You relate to what she’s doing. But that can sometimes be easily dismissed.”

Lee had her detractors. But, Wolfe says, “She always had major representation. She was one of the most successful artists of her era. We tend to think of it as more serious if painting deals with trauma and doubt and it’s big and turbulent and dramatic. If art speaks to tragedy or something we think of those things as big and serious. You think of the New York School — Pollock and Rothko — and big gestures. But why not think of joy as this incredibly profound experience that ties us together?”

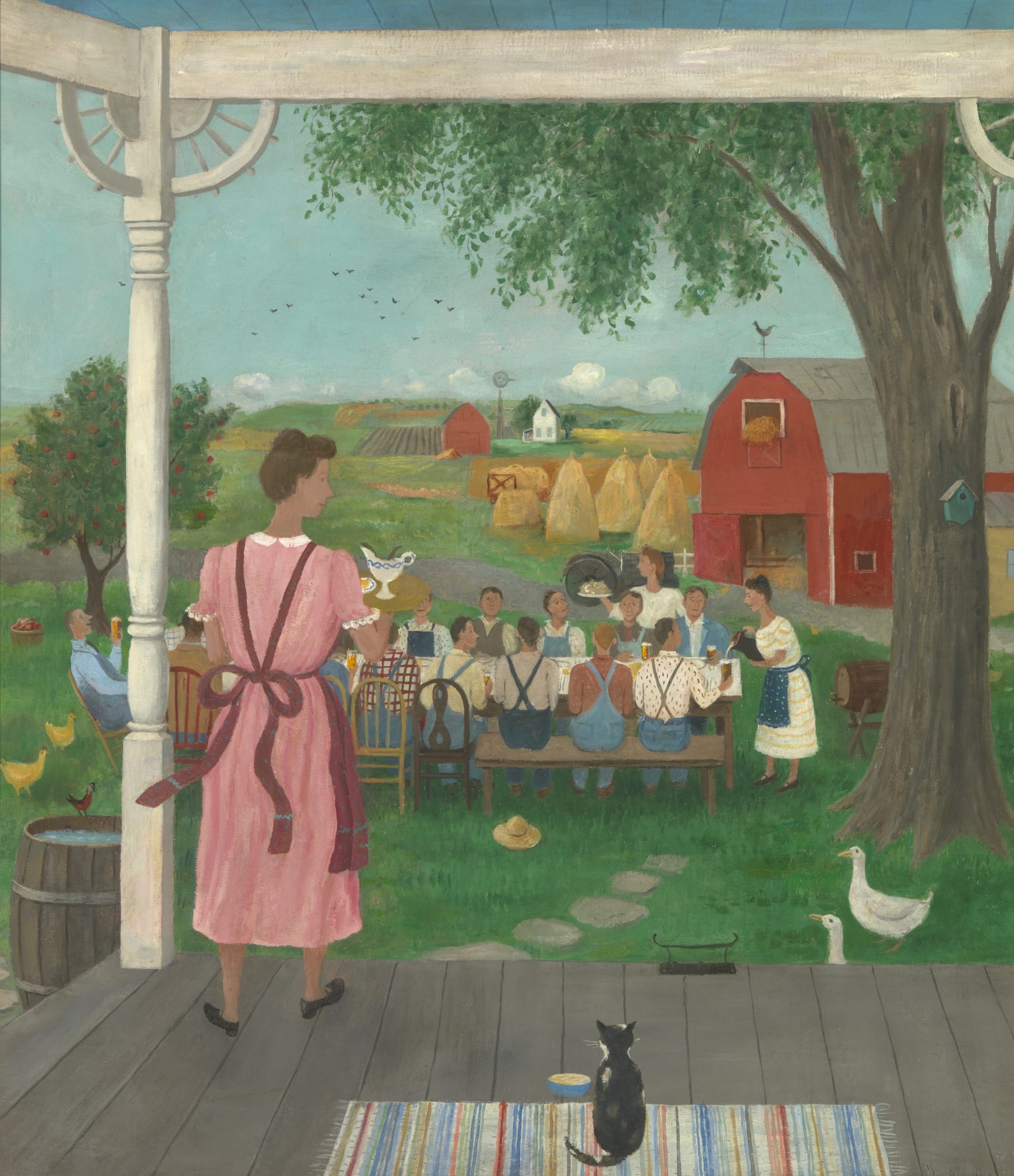

Lee’s works in the ’40s, which are more on the folk art side, are what draw me in. The subjects include people celebrating a family reunion around a long dining room table, building a new house in the country, and people conducting an outdoor dance rehearsal.

“We inevitably relate to it,” Wolfe says. “You think of things in our own wide world. You think of a beautiful spring day or a horseback ride we had. It pulls us into our own memory and our own experiences. It’s important enough to us that they’re still in our memories.”

Wolfe was always attracted to Lee’s work and she wanted to do a show on her. She feels Lee was one of the “American scene artists” from the 1940s and ’50s who “was one of the most successful and still maintained an artist vision and coherence.”

Lee’s work was “not just pretty and lovely — all the things it got called even in her own day.”

Her paintings are figurative and she “simplified things,” but she also does “profound things” in her work, Wolfe says. She was a “colorist” and her paintings are “incredibly designed.” “I just think it’s very sophisticated in a way we sometimes too readily overlook.”

Lee’s paintings in the ’40s and into the early to mid-’50s were “simplified narrative” works. Her painting style evolved to works with “often very little action, sometimes abstract.”

She wanted her later paintings to be “calming and meditative,” Wolfe says. “She felt that an artist has one subject. And they might change how they get to that subject. But the subject is always the same.”

Lee was actively involved in the art world, jurying art shows and exhibits. She also was “very engaging,” Wolfe says. “She knew Gottlieb, Rothko, Grant Wood. So, she was well aware of what was going on. And like any other artist, she was looking and thinking about ways to get at her subjects.”

But it boiled down to one thing, according to Wolfe. “Lee said, ‘My subject is life and the world around us.’”

Lee, who had a home in the Florida Keys and in Woodstock, New York, relied on her memory and “what comes to mind” when she painted. She considered memories as “good at distilling down the most important factors” of what she wanted to paint, Wolfe says. “She changed her style to get better at that.”

“Garden in Moonlight” shows Lee’s work evolving from the strictly narrative. It’s a view from a porch, but it’s not like her 1945 painting, “Harvest Time.” That one depicts a woman standing on a porch watching people drink beer as they sit at a long table in the countryside. “Garden in Moonlight” leans toward abstract. “She wants to get at what it’s like to be alive — the experiences we have. That’s a perfect example. It’s one of my favorite paintings. It’s based very specifically on her back porch. You have to get rid of the world around us and enter the painting. I heard sounds and smells. It’s very serious and it’s very absorbing. That painting, I feel like you hear the sounds of a country night. And the flitting of light through those trees.”

Wolfe says, “Her paintings sort of ask us to slow down and connect to what’s inside of our life and our memories and our own experiences. And it’s very sensory. I think that’s the magic of it.”

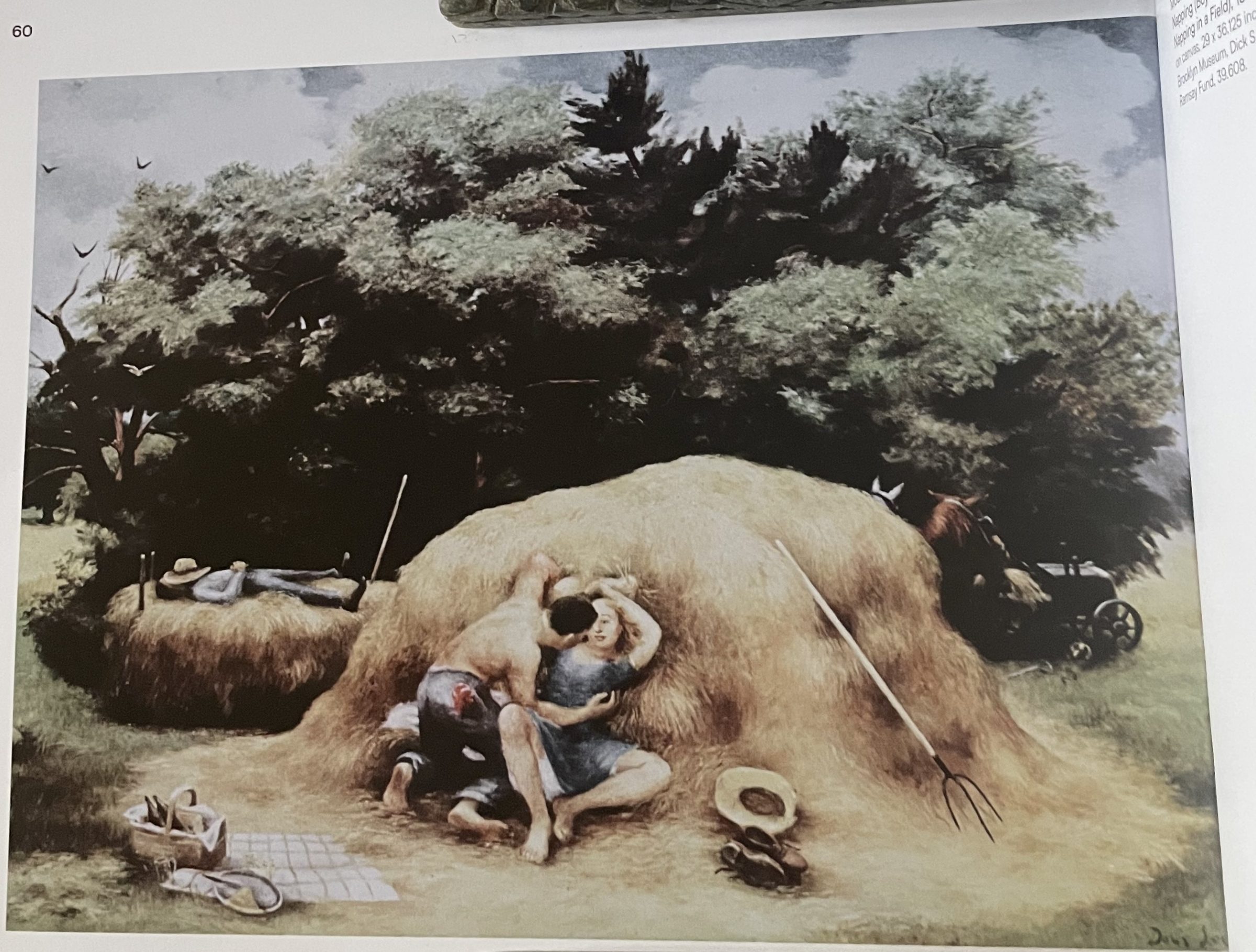

Lee gets earthy on another level, too. In her 1935 painting, “Noon,” which is featured in the catalog, a shirtless, barefooted farmhand with his hat and shoes nearby is on top of a clothed also barefooted reclining woman behind a hay stack. A lot of sexual innuendo is included in the painting.

“Noon” by Doris Lee

(Credit: Estate of Doris Lee, Courtesy of D. Wigmore Fine Art in New York )

“That painting is lost. It’s been lost for decades. We only know it from reproductions. That’s an early painting. And I think, again, that shows this perspective of the world from a woman who is comfortable being a woman.”

And, Wolfe says, “I also think one of things that ties her work together is this female experience.”

Lee, who was so prominent, was “almost always the only female on a teaching faculty,” Wolfe says. “She gave a talk on women in the arts. And she said women need to embrace their sex. They need to embrace being female and who they are. She felt femininity was as powerful as masculinity.”

Julie Pierotti, the Martha R. Robinson Curator at the Dixon, worked with the “Simple Pleasures” curators to bring the show to Memphis. Lee’s painting, “The View at Woodstock,” which is on the cover of the hardback catalog, belongs to Dixon trustees Susan and John Horseman, who live in St. Louis. “They heard we were working on a show and said, ‘We want to be a part of it,’” Pierotti says.

In addition to the Horseman’s painting, Dixon added other paintings, including one of the paintings about the Broadway show Oklahoma! that Lee did for Life magazine. That painting is on loan from a Memphis couple.

Pierotti also is a fan of Lee’s paintings. Her paintings from the ’40s are “like a warm hug,” she says.

But they’re more than that. “They’re so approachable and so inviting and non-intimidating, but spend time with them and they’re pretty complex. There’s more than meets the eye.”

Talking about Lee’s 1945 painting, “Prospector’s Home,” Pierotti says, “It looks like a folk art painting, but if you look at it again, you feel ghost forms in it. Where there’s an outline of a duck, an outline of a water pond. And the mountains in the background are kind of these zig-zag lines. What seems, originally, like this naïve picture, really shows her awareness and embrace of modern art. Early twentieth century art. It looks in some ways like folk art, but when you look at it again, it’s got a lot of depth to it. As Melissa says in the catalog, they (the paintings) are about depicting joy in the format of serious painting.”About Lee’s detractors, Pierotti says. “Some people saw her work as maybe not serious because it’s about happy things. But that made her so popular as an artist in her time. She was very well known in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s.”

She did paintings for Lucky Strike cigarettes and Maxwell House coffee. She also got work from magazines. “That’s the part of the story that’s really interesting to me,” Pierotti says. “These paintings that are so American and so sentimental — kind of in the best way — many of them were done for ads for major corporations.”

And, she says, “On top of that, Doris Lee is the main woman getting these commissions.”

“Simple Pleasures: The Art of Doris Lee,” Pierotti says, “is just a happy show that feels right in 2022 and 2023 to remind us of why we love art. I think it’s kind of the emotions that her paintings evoke and theories they evoke in us.”

And, she adds, “The feeling you get stays with you.”

“Simple Pleasures: The Art of Doris Lee” runs through Sunday, January 15th at Dixon Gallery and Gardens, 4339 Park Avenue. Free admission.