Citizen Kane rightly has a reputation as a landmark of filmic innovation. But what Orson Welles did was not so much invent new techniques as push existing technologies to their full potential. Gregg Toland, the cinematographer whose work was so integral to Kane’s aesthetic that Welles insisted their credits appear together on-screen, had been working in Hollywood for a decade; writer Herman Mankiewicz had been punching up scripts since the silent era. Welles’ genius was synthesis. He saw new ways to put the pieces together.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is not Citizen Kane, but producers Phil Lord and Christopher Miller have seen a new way to put the pieces together.

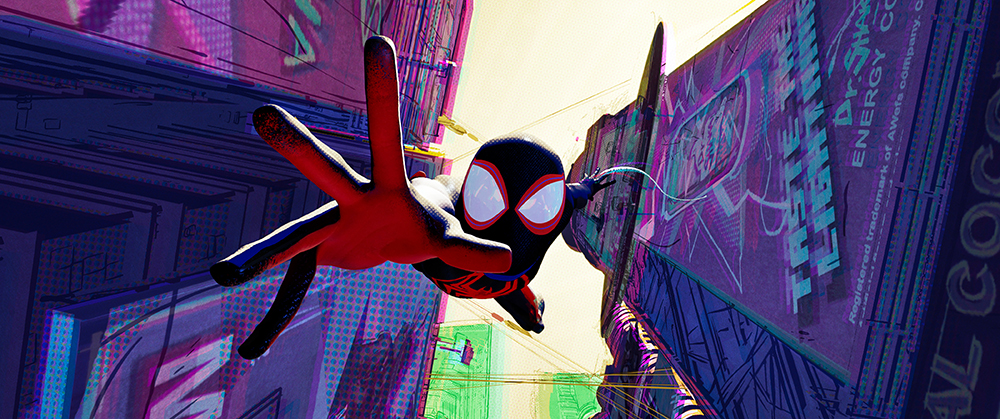

They have a lot of pieces to play with. There are officially three directors: Portuguese animator Joaquim Dos Santos, who cut his teeth on Avatar: The Last Airbender; Justin K. Thompson, a veteran production designer; and Kemp Powers, the playwright behind One Night in Miami and co-director of Pixar’s Soul. The animation team is by far the largest ever assembled. 2018’s Into the Spider-Verse’s credits boasted a then-unprecedented 140 animators — for the sequel, it’s more than 1,000. Pity the poor payroll people! The battalion of artists takes the audience on a 140-minute tour of everything that is possible with digital animation in 2023. The film is a nonstop flurry of visual styles, all mashed up together. The miracle at the heart of Across the Spider-Verse is that it all meshes, and somehow makes sense.

The first line spoken in Across the Spider-Verse comes from Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld). “Let’s do things differently this time,” she says, before the film blasts through your defenses with a thundering drum solo and a visually dazzling sequence that imparts more plot information than most M. Night Shyamalan movies. I briefly thought, “They can’t possibly keep up this pace,” but they hadn’t even floored the gas pedal yet.

Ostensibly, Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) is the lead spider, but this is Gwen Stacy’s movie as much as it is anybody’s. She comes from Earth-65, a reality where she was bitten by the radioactive spider, and her love interest Peter Parker (Jack Quaid) died in her arms. Her father George (Shea Whigham) is a police captain who thinks Spider-Woman killed Peter Parker (which is kind of true, but he had turned into a giant lizard at the time. It’s complicated). Alienated from her family, Gwen is recruited by the Spider-Society. Different versions of the same dimensionally disastrous accident at the Alchemax particle collider from Into the Spider-Verse played out in different ways over the countless realities of the multiverse. Many of the Spider-Man variants, now alerted to the possibility of multiverse travel, have banded together to address existential threats to reality. The most pressing of which is The Spot (Jason Schwartzman), a former Alchemax tech who accidentally gained quantum powers in the explosion.

The Spot’s motivation is similar to Jobu Tupaki’s in Everything Everywhere All At Once: They want to collapse the diverse existences of the multiverse into a singularity contained within themselves. It’s kind of an ultimate, all-encompassing narcissism that stands in contrast to Marvel’s wisecracking, everyman hero. There’s enough Spidey for everyone to identify with, from Pavitr Prabhakar (Karan Soni), aka Spider-Man India, to Jessica Drew (Issa Rae), a Black, no-nonsense, motorcycle-riding Spider-Woman.

Each Spider-person is drawn in their own style, which they maintain even as they travel from world to world. Spider-Punk (Daniel Kaluuya) is especially striking, with his cut-and-paste aesthetic. The collage effect isn’t just for show; it helps build emotion. During Gwen’s emotional confrontation with her father, her watercolor world weeps with her.

Across the Spider-Verse will be viewed as a landmark in animation, and rightfully so. In the future, it may also be seen as a standard bearer for a new artistic movement. Like Rick and Morty and Everything Everywhere All At Once, it is a multiverse story, featuring different versions of the same characters interacting over a sprawling variety of settings. But there’s something deeper going on, too; a maximalist reaction to decades of minimalism and primitivism. As seen in Moonage Daydream, Brett Morgen’s experimental biography of David Bowie, it embraces post-modernist remix, while pointedly rejecting PoMo’s nihilist tendencies in favor of an effusive humanism. I’m not sure this nascent movement has a name yet, but it’s awesome, and I want more of it. While I’m waiting, I’ll go watch Across the Spider-Verse again.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Now playing

Multiple locations