Pressureua | Dreamstime

Pressureua | Dreamstime

When Steve Jobs came to Memphis in 2009, the first objective was to save his life. The second objective was to protect his privacy. Both operations were successful due to extraordinary efforts.

Jobs died last week at the age of 56. He owed the final two and a half years of his life to a liver transplant he underwent at the UT-Methodist Le Bonheur Liver Transplant Center at Methodist University Hospital. Dr. James Eason, director of the center, performed the surgery and now lives in the house at 36 Morningside Place in Midtown where Jobs and his wife, Laurene Powell Jobs, lived during their Memphis stay.

Steve Jobs was a guest among us. Neighbors were aware that someone important was moving in when they saw trucks carrying carpenters, painters, and plumbers suddenly descend on the house that spring. The identity of the new occupants was first a mystery, then a guessing game, and finally a secret that is still protected. People familiar with the story shared it with the Flyer on condition that their names not be used.

The secrecy was due to business considerations as well as personal preference. Rumors about the health of Jobs, who was treated for pancreatic cancer in 2004, moved Apple’s stock price up or down, especially after an emaciated Jobs addressed a software conference in 2008.

As Harris Collingwood wrote in a story in The Atlantic in 2009, “Apple’s close-to-the-vest PR policy has opened ample space for rumors to grow. Jobs’s instinct for concealment has spread throughout the company; reporters’ inquiries into almost any corporate matter are routinely rebuffed. And when Apple does make an official comment about Jobs’s health, it manages to undermine its own credibility. In light of subsequent revelations, the company’s brush-off remark that Jobs was suffering from a ‘common bug’ at the June 2008 conference seems disingenuous at best.”

The Memphis chapter of the story began in January 2009, when doctors at Stanford University diagnosed Jobs with advanced liver disease. His prognosis was poor. His family, close friends, and eventually the transplant center in Memphis were told that he was terminal.

Except for the distant hope a successful transplant might offer him, his days were numbered. His Stanford medical team searched the world for the best place and the best doctor to give him a transplant. Their choice of the UT-Methodist Le Bonheur Liver Transplant Center and Eason was based on their professional reputation and Memphis logistics. Once it was available, the donor liver had to be shipped to the transplant center and the operation had to be done immediately.

Jobs’ doctors considered Eason’s liver transplant team the best in the world. Could they take him? Would his fame and wealth help? No, it wouldn’t. There are more transplant candidates than suitable donors, and the life-saving selection is governed by a strict protocol based on need relative to others and odds of survival when the liver became available. Eason said months after the operation that the decision was made by an independent medical panel based on a blind record that did not identify the patient.

That meant Jobs needed a place in Memphis to wait as long as he had to and, assuming all went well, recuperate. It had to be quiet, comfortable, and, as much as possible, sanitized from the risk of fatal infections. Green grass and trees were desirable, but above all, it had to be private.

In March, a man in a dark suit and driving a rental car came to Midtown to make the arrangements. It was not Steve Jobs but a close friend, an Apple lawyer named George Riley, who had grown up in Memphis and still had local connections.

The house that he wanted was the residence of the former chancellor of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. Riley immediately bought it, titling it to a limited liability corporation or LLC, which gave no clue to the future occupant.

The neighbors knew none of this until one weekday morning, when it became evident that something was up. Workers arrived in force and came back every day, including Saturday and Sunday, for more than a week. And then they were gone as quickly as they had come. Occasionally, the man in the dark suit would come around but never introduce himself.

When the neighbors asked the contractor who owned the house, he said he didn’t know. All he knew was that they were from out of town and wanted to fix some things before they moved in. That seemed suspicious, as many of the neighbors had been in the house and knew that it was in fine condition. Why would somebody be doing all of that work just to quiet the nighttime noise of FedEx planes? Why would they want to repaint every square inch? The workmen didn’t know and didn’t really care.

But the neighbors did. The identity of their new neighbor became a guessing game. Jobs’ friends did not discourage this so long as it kept the real story out of the news. One rumor identified the mystery man as actor Robin Williams because he had a brother in Memphis, but a few days later it was learned that Williams had undergone an operation in Cleveland, not Memphis. Others speculated that a rich foreigner with a sick child at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital had bought the house, a red herring that was both logical and helpful as far as keeping the secret.

Jobs, of course, was also mentioned, since his illness and six-month medical sabbatical had been widely reported. A blogger wrote that Jobs’ plane had been parked one night at Wilson Air in Memphis. Another blogger identified Jobs but got the house and address wrong. A Memphis television crew cruised the street asking joggers, “Where does Steve Jobs live?” Freelance photographers staked out the neighborhood and the entrance to St. Jude, which was the wrong hospital. But there were no confirmed sightings, and officials at both hospitals who knew the facts would not talk about them, at least not then. With Jobs’ permission, Eason would later speak publicly about the transplant operation.

One tantalizing clue was an attractive blond lady who was seen walking early on spring mornings. Strangers walking on the pretty half-circle drive near Overton Park were not unusual, but this one never tarried or introduced herself. At least one neighbor deduced that she was Laurene Powell Jobs. But instead of spilling the beans, neighbors abandoned their guessing game and, wary of television cameras and helicopters, undertook the job of “protect our new neighbor.” The house was even blacked out on Google Earth.

By the time he got to Memphis, Jobs was so gravely ill that it was feared that he would die before getting a transplant. One of the few people allowed to visit him in Memphis was Al Gore. The former vice president, an Apple board member, arrived at the Memphis airport in jeans, baseball cap, and sunglasses and was either not recognized or not bothered.

Jobs stayed in Memphis for only a few weeks during his recovery. At least one person saw him in a wheelchair in Overton Park and recognized him but did not speak to him. Then in April, the house on Morningside was empty again. The black SUVs and the man in the dark suit didn’t come around anymore. In a few days, the announcement came from California: Steve Jobs had been operated on in Memphis. He had survived. He was at home with his family.

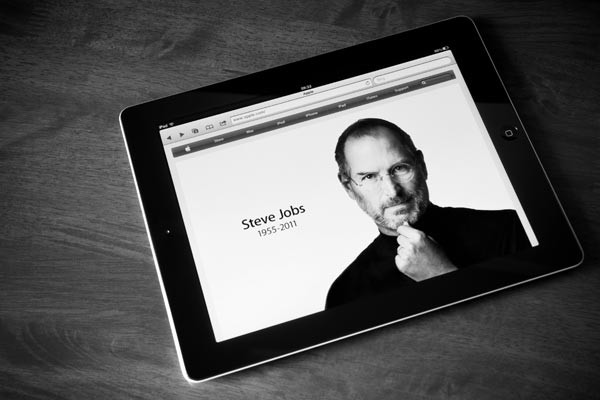

A few weeks later, he came out in his signature black pullover to release his new iPad. The Memphis mystery man was back on the job. Apple’s stock price, which had fallen below $100 a share in early 2009, began a rally that has carried it to nearly $400 a share this year.