I’ve told this story may times: It concerns what I still regard, some 30-odd years later, as the greatest compliment I’ve ever received (or am ever likely to receive), and it bears on this “N-word” issue.

It was back when I was teaching English at Memphis State (which is what the U of M was called then). I had just come from one of those perfect class sessions that every teacher is familiar with. We had all been in on the moment, teacher and student alike — which is how it goes when you’re bonded right. In the Zen manner, there was an It at work, and we were all in It together. Thoughts and insights were coming in from everywhere, the energy level was high, and on such days it was no trick at all for me to hold up my end as pedagogue and pacemaker.

After class, I went over to my office across the hall in the Patterson building, and directly was visited by a young female student from the class — an African-American, though “black,” which remains acceptable, was the term of choice back then. She just didn’t want the moment to end; so we sat and relived the high points.

She was — how to say it? — kind in her estimate of my role.

“You were doing this, and you were doing that,” she was saying excitedly, “and I was thinking, ‘Look at that nigger go!’”

And then, realizing what she had said (for the record, I am a plain white Caucasian), she became embarrassed and began trying to stammer out an apology. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to say that…,” she began.

“No, you don’t,” I said, in the friendliest voice I owned, from someplace high up in the stratosphere. “Don’t even try to take that back. That’s the best compliment I’ve ever received.” It was, and it remains so, for all the reasons you would expect and some you wouldn’t. Recalling E.B. White’s injunction against over-dissection, I’ll still give the subject a brief whirl.

Anybody who has been out and about in the diversified world we live in has heard the N-word employed, fairly liberally, by African Americans in conversation with each other. Not all, to be sure, but many — and often enough for an outsider not to miss it.

“Who’s that nigger that used to go with your sister?” one might overhear. To which the answer might be, “You mean that bright nigger?” (“bright “meaning light-skinned). An innocent usage, as almost all such intramural uses of the word are innocent. It’s a kind of easy vernacular, for which the white equivalent might be “dude.”

And sometimes it’s employed as a straight-out descriptor. Earlier this week I was walking through the men’s department at the Wolfchase Galleria Dillard’s and overheard several young black men discussing a particular garment on sale. “Naw, man, a nigger can’t wear that!” one was saying. And there was a world of nuance in it.

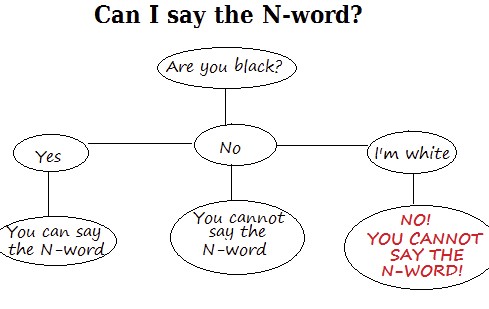

But it’s more, too. Ultimately, the use of the N-word among African-Americans is clearly a kind of self-imposed identifier, a badge of intimacy. Even of pride. And no white need apply.

For one thing, and this is where things get so very, very subtle that I’m not even going to try examining in detail, the term implies not only clanship but a kind of superiority that is one part unfeigned naturalness — honesty, even — and several other parts relating to specific ingrained ways of being and performing: social, physical, intellectual, what-have-you. (Yes, I think I can identify some of these, but I’m going to pass on it just now.)

Let’s just say that for a white to be graced with the N-word by a black is maybe the exact obverse, connotation-wise, of a black’s being called that by a white. It comes from a whole different lexicon than is currently the subject of so much spoken and written discussion — some of it keen, some of it blather.

There was a time, back in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s when some white folks with impeccably hip credentials used to wield the N-word with great ease and abandon — with the implied understanding that they were using it in the black way, with no intent or implication that could be called racist.

Except that words aren’t so easily appropriated and corralled. And so hip (and good) a man as the late populist music master Jim Dickinson, who used to travel in such circles and speak in such manner, surely nailed it for the whole breed when he pointedly gave up using the term a decade or two back, having come to the realization that it was a presumption to do so, however well intended.

But there still are circumstances in which — said by the right sayer and meant in the right manner — it can be a grace word, believe it or not. That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it