Originally displayed at New York’s Museum of Biblical Art last spring, “Ashe to Amen: African Americans and Biblical Imagery,” now on display at the Dixon Gallery & Gardens, is an exhibition of rare understanding, drawing together the work of artists who articulate the divine without disavowing the mundane.

The exhibition spans generation and genre. The striking realist oil paintings of Memphis’ own virtuoso Jared Small are displayed alongside Romare Bearden’s powerful civil-rights-era collages. The works of visionary folk sculptors William Edmondson and Elijah Pierce keep company with Harlem milliner Evetta Petty’s contemporary church hats.

Curator Dr. Leslie King-Hammond makes it clear that “Ashe” is not a collection of religious art, even if some of the work is about divine encounters or the meaning of scripture. (“I’ll leave scripture,” she says, “to the theologians.”)

Oletha DeVane, Fall From Grace, 2013, glass, beads, casings, plexi and fabric, collection of the artist

The exhibition is more focused on politics than preaching. Its concern is with how the spiritual can co-exist with — or be catalyzed by — the profane. What is so prescient about “Ashe” is how this age-old polarity in art (the knowable and the unknowable, the decaying and the eternal, the earthbound and the transcendent) is wrought out of the objects of a familiar, violent history. The physical artifacts of diaspora, segregation, and slavery are invoked powerfully in artworks that transcend that physicality.

Sculptor Oletha DeVane’s Fall From Grace is formed from clay, a broken wine bottle, beads, and animal bones. The bottom half of the sculpture is lit by a bulb that is partially concealed within a white globe. The globe is encrusted with ceramic snakes, their bodies supporting a red, bejeweled wine bottle that forms the middle of the piece. Bones fan out from the top of the bottle like wings. Scrawled on the bones are the words “misleading,” “power,” and “deviant.” DeVane’s sculpture is intended to call out corruption within the Christian church. It does so obliquely, as an object of beauty. The light that emanates from within the work draws attention to the message of the exterior, but it also dwarfs it.

Jonathan Green, Seeking, 2006, oil on masonite, collection of Mepkin Abbey, Clare Booth Luce Library, Moncks Corner, South Carolina

Jonathan Green’s incredible painting, Seeking, describes a Gullah spiritual practice of searching for God alone in the wilderness. Like DeVane’s sculpture, the light source in Seeking comes from the interior of the work. Spiritual seekers sit amidst red-orange trees and bright-green long-grasses, all of which seem to emanate their own glow. The effect is that the simple scene has profound atmosphere. No overt symbols are needed to convey its message.

Some works combine the heaviness and complexity of material presence with forthright image-making. Angel, a painting by Benny Andrews, uses collaged rag fabric to portray a female harpist. The fabric is rough and crusted with paint; the harp strings formed out of thin rope. The woman’s hair is drawn up as if she has been laboring. She stands against a light-blue sky, almost to scale with the viewer.

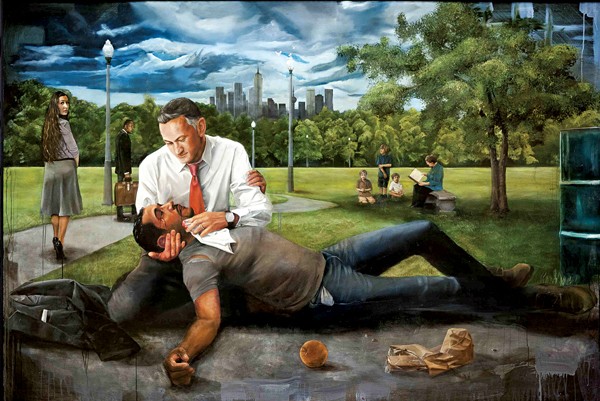

Jared Small, The Good Samaritan, 2012, oil on panel, collection of Dina and Brad Martin

Even pieces that can be read as commentary, such as Jared Small’s retelling of the Good Samaritan in a contemporary, metropolitan context or Charles Alston’s illustrative take on a home funeral, Midnight Vigil, display a distinct intimacy. These works are retellings, but they are not recitations. They serve as austere companions to expressive sculptural works, to a hewn glass pulpit or a gilded quilt.

The exhibit is most powerful when it is most direct.

Renee Stout’s Church of the Crossroads occupies its own gallery. A neon sign, spelling the title of the piece, cracks and fizzles. A white band of neon, shaped like something between a chapel and a Klan hood, encircles the piece. It looks like the back of a one-room bar. It sounds like an abandoned Southern street at night.

Stout’s piece spells it out. The artists in “Ashe to Amen” work at a crossroads: of faith and doubt, of the act of creation and the act of closure.

Through January 5th