JB

JB

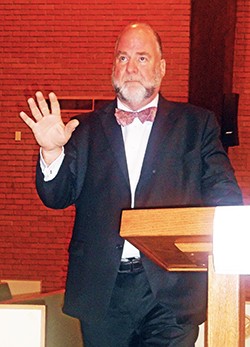

Juvenile Court Judge Dan Michael

Juvenile Court Judge Dan Michael does his best to hit the middle. Addressing a group of adult citizens at Asbury United Methodist Church in Fox Meadows last week on the nature of his job, he was equal parts affable and professional. “My first name’s Dan,” he told his audience. “That’s what you call me, unless you’re in court. When you’re in court, it’s ‘Your Honor’ or ‘Judge.’”

The occasion was a meeting of the Southeast Memphis Betterment Association (SEMBA), a biracial civic organization serving the Parkway Village/Fox Meadows area, and Michael had no problem discerning what he supposed to be their immediate concerns — “some incidents that have set this county on edge [with] juveniles involved….,” i.e., the recent youth-mob attacks, three weeks apart, at Poplar Plaza and in the aftermath of a Friday night football game at Crump Stadium.

“My wife was speechless, seeing it on video, but I see it all the time,” said Michael, who went on to define his role as upholder of a system of laws that are “the antithesis of the mob reaction.”

Citing the Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 37, Section 1, from which Juvenile Court derives its authority, Michael defined that role as one of providing “care and protection [and] wholesome moral, mental, and physical development’ of juveniles, while, “consistent with the protection of the public interest,” removing “from children committing delinquent acts the taint of criminality and the consequences of criminal behavior and substituting therefore a program of training, treatment, and rehabilitation.”

Giving the SEMBA members a few seconds to digest that bit of primer information, Michael emphasized, “Nowhere is the word ‘punishment’ ever used. Nowhere.”

Acknowledging that some of the juveniles he deals with administratively — though by no means a majority, as he would make clear — are accused of “murder, rapes, aggravated assault, and kidnapping,” Michael said, “They do adult things, but they are not adults, they are children.” His job was “to take the time and make the effort” so that an offending child “of 16 or 17 years, with the right guidance has a chance” at life.

In a nutshell: “My role is to save that child’s life while protecting you.”

In the lexicon of the law as it applies to his office, said Michael, “Juveniles do not commit crimes. They commit delinquent acts. They don’t get arrested. They are ‘taken into custody.’” He had prefaced this definition with a confession that, as a juvenile himself, in a career that would see him become, progressively, an auto mechanics, a businessman, a lawyer, a Court officer, and finally a judge, he had himself been a transgressor.

“I got away with some things, some that would get people in prison, like the simple possession of certain drugs,” noted Michael, whose burly presence, coupled with his evenly stated and precisely enunciated manner of speaking, gave his words a quiet but obvious air of authority.

“A life is worth something,” he said.

“What are your chances of running into dangerous children?” he asked, proceeding to do the math. Of the 112,00 between the ages of 10 and 17 in Shelby County, roughly 9,000 come before his court, and, of these, some 1300 are found guilty, or, in the special lingo of Juvenile Court, have the charges sustained. And, of those 1300, only about 400 can be considered serious offenders, Michael said. So there was “a very, very small chance” that the juveniles that his audience might encounter on the street, “anywhere in Shelby County,” would be dangerous.

Michael, a former chief administrator under former Judge Curtis Person and a veteran of 20 years in the area of juvenile justice, was firm on a key point. “We cannot incarcerate ourselves out of crime.” The solution, he said, was “a sea change in the way children are cared for by their parents.” There were 6700 cases of parental abuse and neglect before the courts last year, compared with 3400 cases of juvenile delinquency, he said, and juvenile offenders arose from “toxic environments” where violence was recognized as the way to solve problems.

Last year, the cases of 90 juveniles, “my lost kids,” had to be transferred to “the adult system” for administration, Michael said, with an air of what seemed to be unfeigned sadness.

“It is my Intent to hold parents responsible” where parental negligence was evident, and to “use my authority” to impose judicial remedies on parents, including jail time, where necessary.

|

He talked with regret of numerous county-administered correctional programs that had been taken over by the state or shut-down, apparently for budgetary reasons, but spoke with optimism of private initiatives like Stevie Moore’s F.F.U.N. program to combat youth violence or recent offer from Shelby County Commissioner Heidi Shafer to organize an adult mentoring program for youths in the High Point area, site of the Poplar Plaza incident.

According to Michael, “the kids at Kroger,” where the violent incident took place, included “a bunch of really good kids,” mixed in with “a few bad apples.”

Michael was asked a recent speech by City Councilman Harold Collins implying that sterner and more immediate justice might be imposed at Juvenile Court than is permitted by procedural reforms currently being monitored by the U.S. Department of Justice.

While praising Collins for some of the Councilman’s own mentoring efforts in tandem with General

Sessions Court Judge Loyce Lambert Ryan, Michael said, “He’s running for mayor.” He said the Court itself had initiated most of the reforms currently under way. The right balance was somewhere” in the middle,” and “I’m all about the balance.”

And the outlook, in Michael’s view, was not necessarily bleak. He touted the prospect of something called “blended sentencing,” which would basically allow for an extension of Juvenile Court’s oversight in certain cases of youthful offenders who had reached adult status and said that a variety of little-known but highly successful Court initiatives already under way, including a Safe Schools program and a ”model dependency court” had attracted much attention and interest outside Shelby County.

“We’ve been on the cutting edge of some of the best stuff in this country,” Michael concluded emphatically.