This afternoon I popped the old Citizen Kane DVD in the Blu Ray player and sat down to fast forward through to the parts about politics. I ended up watching the whole thing, not only because it’s the legit best movie ever made, but also because it’s pretty much all about politics.

It’s the sign of a great work of art that you can see something new in it every time you experience it. Orson Welles’ masterpiece is film’s version of the Great American Novel; it’s the story of a specific person who stands in for something in the national character. Charles Foster Kane is the national character, in the same way the bald eagle is the national bird.

If Welles’ only involvement with Citizen Kane was as its lead actor, it would still be one of the greatest achievements in film history. Welles plays Kane at almost every stage of his life. (Even Buddy Swan, the young actor who plays Charlie at age 8, bears a frightening resemblance to Welles.) The details of Kane’s life are famously based on newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, but I think Welles was going for something deeper than a thinly veiled biopic. Citizen Kane is about the kind of person who would seek power.

One of the great gifts George Washington gave to American democracy is the reverence for Cincinnatus, the Roman general who, when given dictatorial powers over the Roman Republic, resolved the military emergency, handed in his crown, and returned to his farm. The most worthy leaders, we believe, should be those who serve reluctantly, recognizing the corrosive effect of power on the soul of the wielder.

Kane is not like that. Upon taking control of his newspaper, the fictional New York Inquirer, his first act is to lower the editorial standards and print sensation instead of what the stodgy old staff considers news. Later, he abuses the power of the press to drum up a fake war that becomes a real war—his motivation, like Hearst’s, seems to be beyond just selling more newspapers. Kane starts a war just to see if he can.

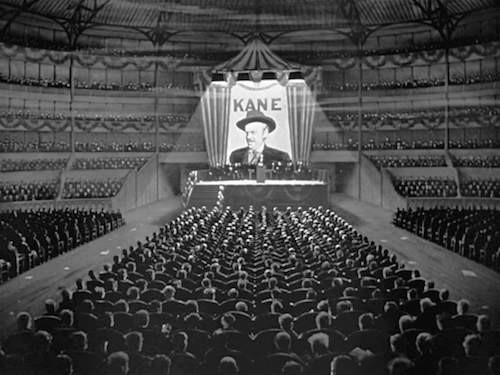

But, just like Roger Ailes’ fall from the pinnacle of Fox News, his lax journalistic standards come back to haunt him. When Kane runs for Governor of New York, he claims to be, as his best friend Leland (Joseph Cotton in a performance for the ages) says, “the great liberal.” Next we see Kane giving a stump speech in a scene that would not look too out of place on the 2016 campaign trail, and his pitch is pure demagoguery. He claims to be fighting for the “underpaid and underfed”, but his only real policy pledge is to arrest and prosecute his political opponent, the allegedly corrupt Governor Jim Gettys (Ray Collins). But Kane the political dilettante gets his comeuppance that very night, when Gettys reveals what a real cutthroat politician can do. Kane has been having a typically reckless affair with the cabaret singer Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore), and Gettys gives him a taste of his own medicine by ensuring the story gets splashed on every newspaper in the state that Kane doesn’t own, generating delightfully written headlines such as “Entrapped By Wife As Love Pirate, Kane Refuses to Quit Race.”

Like Donald Trump, Kane is a spoiled rich boy. “I always gagged on the silver spoon,” the unreflective Kane says as he is being deposed as the head of his media empire. “If I hadn’t been rich, I could have been a really great man.”

Leland says all Kane ever wanted was love, and he ran for office to get the voters to love him. Like most politicians, his personality is built over a bottomless hole that can never be filled. Welles, however, is hinting at something more complex. The last time we see Kane in the film, he’s a beaten man, walking between two mirrors that create an infinity of reflections, as if his relentlessly self-constructed identity has been shattered, and all that is left are shards of imperfect images. Ambition is our national malady, and too much is inevitably fatal. As Kane himself says in the opening newsreel detailing the events of his life, “I am, have been, and always will be one thing: An American.”