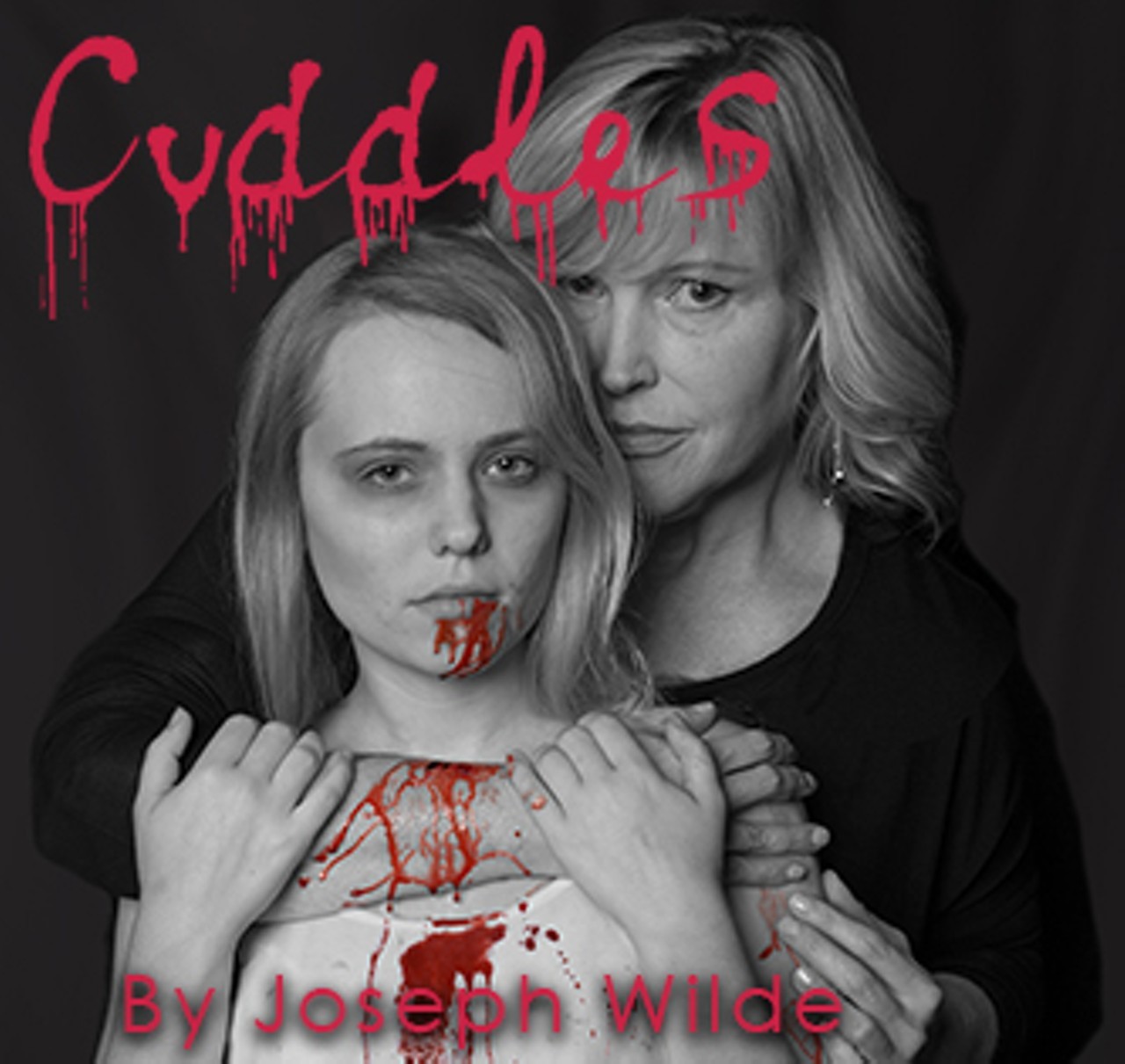

Tracie Hansom and Hayley Hellums

I no longer possess a copy of The Amityville Horror, so don’t expect me to quote it directly. But I devoured the paperback when it was new, and I was too young to get into an R-rated picture. The line that scared me most explained the mundane triggers for demonic haunting. Supernatural horror, it said, might appear and disappear suddenly. It might be caused by something as simple and ordinary as “rearranging the furniture.” For some reason that line stuck with me, and it pops into my head whenever good plays with strong directors and gifted casts don’t seem to work. I wonder how many haints and horrors might be driven away by better design — Or at least by a simple shuffling of the chairs.

Cuddles is a different kind of vampire mystery. It unravels slowly, strangely, evoking a grinding sense of dread that grows minute to minute. At core, it’s a modern fairy tale with gothic elements ripped from 19th-Century novels where everybody seems to have a mad or embarrassing relative locked in the attic. It’s the story of Tabby, a well off, not very nice woman, and Eve the bloodsucking little sister she cares for. There are men in this story too, and although we never see them, they often feel like the play’s realest characters. Their influence erodes a system of rules and rituals the sisters created to protect each other from “the hunger.”

[pullquote-1]Cuddles is clever, but New Moon’s cast is struggling. Conversations (one-sided, per the script) turn into droning monologues. But when Tracie Hansom and Hayley Hellums connect it’s horrible, hard to watch, impossible not to watch, and everything you want from a revisionist nightmare. They’re good together, but disadvantaged.

Most of the action is pushed as far upstage as possible and confined to a smallish platform floating in the comparatively immense darkness. The effect isn’t one of claustrophobia — which would be appropriate — but distance. The play’s less active moments happen in this big dark gulf between the audience, and a perfectly revolting little attic set.

Maybe the audience could have been drawn in closer, and assembled on three sides. Maybe the attic set could have been brought to center stage. Distinctions might even blur and the attic and outside word could bleed together — literally and figuratively. Point being, there’s a lot to like about this spook story. But somebody needs to rearrange the furniture.