Georgia A. King, 76, is a Memphian who needs her floral-decorated cane to assist in her instantly recognizable, purposeful stride. Whenever she steps out of her apartment near Victorian Village, she is likely to encounter grins and hugs from other Memphians as she makes her way around to her various destinations.

Most call her “Mother King,” a moniker earned from her reputation, built by decades of organizing work for Memphis’ poor and her involvement with the civil rights movement.

Since she herself relies on public transportation, pushing for equitable public transportation is high up on King’s exhaustive list of interests and pet projects.

Shortly after the Occupy Memphis protests of 2011, King formed a Transportation Task Force, which would become the Memphis Bus Riders Union in early 2012.

later evolve into the MBRU.

No matter where she is in Memphis — or what else is occupying her time — she watches the Memphis Area Transit Authority buses. “I watch for everything. Is the bus let down for disabled passengers? Does the driver look tired? Are the buses running when they are supposed to?”

King is not alone in her vigilance. She is joined by the other members of MBRU as well as the Amalgamated Transit Union Local 713. Together they monitor the pulse of MATA, and right now one of their major concerns is restoring access to the historic, and once well-used Route 31 Crosstown, which was discontinued in 2013.

Crosstown 31 ran primarily along Cleveland and connected many North and South Memphis neighborhoods. For months, members of MBRU have been knocking on doors in tucked-away neighborhoods that used to bookend the 31. Demographically, these neighborhoods are majority black and marked by the all-too-familiar poverty that disproportionately strangles many black neighborhoods in Memphis.

Armed with clipboards, volunteers with MBRU have been asking residents to sign their name to a petition and endorse the restoration of Crosstown 31.

So far, they have more than 1,700 signatures, roughly 900 or so shy of the estimated number of riders that rode Route 31 daily for work and to get necessities, such as groceries, before it was discontinued.

The signatures are important, but they can only change so much, which is why Mother King is hoping city officials are watching and listening to the efforts of the two unions. After all, she says, “If the only people protesting are the ones that need this route, nothing will get done.”

Ron Garrison, CEO of MATA, stands in front of a trolley.

The Cut

When the decision was made to eliminate the 31 in 2013, MATA was facing a $4.5 million deficit in its yearly operating budget. MATA’s then chief executive officer, William Hudson, said that route eliminations would be necessary in order for MATA to continue to operate. Among other route changes that were made that year, a new route No. 42 Crosstown was created that combined and replaced Route 10 Watkins, Route 43 Elvis Presley, and the Crosstown 31.

At the time, Hudson defined vulnerable routes as ones with a low ridership, specifically 25 or fewer customers per hour. However, study findings in the Short Range Transit Plan, a transit study produced by independent consulting firm Nelson/Nygaard just two years prior to its cut, showed Crosstown 31 as Memphis’ third highest-used bus route, with an average of 2,600 riders daily. The route was second only to the 43 Elvis Presley, which funneled 2,700 daily riders between the heart of the city and South Memphis neighborhoods.

If you spread 2,600 riders over 19 hours of operation, the 31 had an average of 136 riders per hour. Unless there was a drastic (and undocumented) decline in Route 31’s ridership in the two years between the study findings and the route’s elimination, the old Crosstown route didn’t fit Hudson’s definition of low ridership.

A few years later, it wasn’t the number of daily riders that MATA officials pointed to in defending the cutting of Route 31. Rather, it was a finding of the same SRTP study that said MATA would save funds by combining two of its five highest-used routes.

Very Long Walks, Very Few Stops

In a September 2016 guest column in The Commercial Appeal, MATA’s CEO, Ron Garrison, acknowledged the movement to restore Route 31 and pointed to the SRTP study findings that said “at the time” MATA would save money forming the new No. 42 Crosstown — which also connects North and South Memphis — by eliminating duplicate routes while still being able to adequately serve customers on both ends.

“Fast forward to today, and MATA still serves those communities with Route 42 and six other routes,” Garrison wrote, specifically referring to the New Chicago and Riverview-Kansas neighborhoods.

At last count, there are 1,700 petition signatures that say otherwise.

“There’s definitely no proof of that,” said Carnita Atwater, the executive director of the New Chicago Community Development Corporation. “Because the 42 won’t circle around some of these neighborhoods.”

Atwater keeps frequent tabs on the residents of the New Chicago area through her work at the NCCDC. Half community center and half museum, the NCCDC is a bustling hub within an economically depressed area. From the building, you can see the towering smokestack of the long-closed Firestone Tire and Rubber Company — a reminder that steady jobs were once considerably more plentiful in the area. Now many of the residents are dependent on the bus to reach their jobs.

Atwater says MATA’s new route isn’t working. “I can tell you that many people have lost their jobs because of [the elimination of] Route 31. We did questionnaires after, and we can verify that.”

Like King, Atwater’s concern is focused on the dozens of smaller neighborhoods that the new Crosstown route doesn’t directly extend to and that feeder routes don’t regularly reach.

“Most people out here don’t even own a bicycle, and walking to the nearest stop certainly isn’t always an option,” Atwater says. And jobs aren’t her only concern.

“Another major concern is families not being able to go into other communities to see family members. And churches. If you live in North Memphis, but your church is in South Memphis, you’re out of luck, come Sunday.”

According to Google Maps, 60 churches are directly on or within a few blocks of the old Route 31.

Down the line in South Memphis, the Riverview-Kansas neighborhood tells a similar tale. Just like New Chicago, recent census data shows the South Memphis neighborhood to be majority black and with a disproportionate amount of residents living in poverty and with a high unemployment rate.

The Riverview-Kansas area wa s once the south loop for Route 31, and it shares the challenges that New Chicago has with MATA’s 31 replacement plan: lots of residential pockets that would require a resident to either walk an hour or more — and cross over an interstate — to access the new Crosstown route, or use multiple bus transfers.

Neither one of those options work for those facing some degree of immobility, or for those who are so financially strapped that transfers must be carefully budgeted.

In fact, data gathered by the Center for Neighborhood Technology, a research-based think tank for urban sustainability, shows the costs of public transportation for residents living in both neighborhoods comprises more than 20 percent of their take-home income.

Coming Soon to Crosstown …

The opening date for the Crosstown Concourse in the former Sears building has been set for May 2017, and among what have been dubbed as the “founding tenants” is Church Health Center, which has as its primary purpose serving the working poor. Its new location in the Concourse means that affordable health care is shifting a few blocks north from the health center’s current location on Peabody, to a location more in the middle of the Midtown/downtown area.

For the new Crosstown bus route, the question becomes whether or not the route and its feeders can efficiently and economically bring residents from New Chicago and Kansas-Riverside to the Concourse for health-care access, not to mention the hundreds of jobs that will be available in the area once the Concourse opens.

“Crosstown, interestingly enough, was called Crosstown because it was once the easiest place to get to in Memphis,” says Church Health Center founder Scott Morris. “It was once where the trolley lines crossed, and so it was the easiest place to get to in Memphis.”

In Morris’ view, current public transit deficits have resulted from a mixture of decades of underfunding and a lack of creativity and cutting-edge solutions from previous administrations.

“I’ve looked at their finances over time, and I don’t know how they do what they do,” said Morris.

For the purposes of the CHC, Morris is more concerned that Memphians reliant on public transit have the routes they need to get to school and work.

“The number one predictor of anyone’s health and outcome is their education, not their doctor,” says Morris. He says that most of the CHC’s patients, at the very least, have their transportation to work figured out, since a person must be employed to receive services from the CHC. But Morris is still concerned about the problems associated with the loss of Route 31 and the problems concerning MATA as a whole.

Referring to Garrison as “intriguing,” Morris says he has spent enough time around MATA’s leader to determine that he “doesn’t have his head stuck in the sand.” While Morris isn’t entirely familiar with all of the dynamics of restoring Route 31, he says it’s a conversation that neither he nor Garrison is ignoring.

Morris says that solutions offered in lieu of Route 31 work for some, but not all. He adds, particularly around Crosstown, that people are “thinking long and hard and deep about this issue.

“I met with Garrison last week, and I was saying, ‘We have to make this work for everyone at Crosstown. It can’t be just about the middle- and upper-class people who are coming there to work,'” said Morris, who continued to say, “I was singing to the choir when I was talking to him. My personal feeling was that he got it.”

Elena Delavega, PhD, University of Memphis Department of Social Work. Research published August 15, 2014.

Elena Delavega, PhD, University of Memphis Department of Social Work. Research published August 15, 2014.

What Everyone Agrees On (Money, Money, Money)

What’s to be done — if anything is to be done — about communities affected by Route 31’s elimination remains to be seen.

But, if there’s one sentiment that MBRU, Local 713, Morris, and Garrison can all agree upon, it’s that decades of inadequate funding of Memphis’ buses have created a swath of problems without clear solutions.

Route 31 has become a focal point for conversation and action, but it’s also just one problem in a public transit system that’s beleaguered by an aging fleet, outdated infrastructure, inadequate bus stop shelters, and sometimes inconsistent stops on established routes.

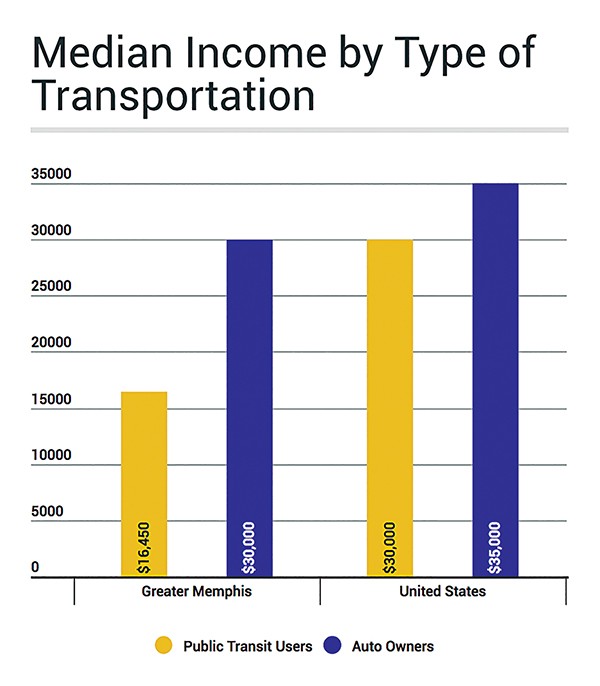

Where there are inadequate transit services, poverty is sure to follow, as we know from mountains of data compiled over the years. The most recent poverty figures (compiled in 2014 by data guru Elena Delavega at the University of Memphis) shows a startling income disparity between those who drive to work and those who use public transportation.

Residents living in the major Memphis metropolitan area who drive to work have a median income of $34,199. The median income for those who use public transit is just $16,450.

If that bus rider’s median income supports more than one person, they are officially below the poverty line. While, it’s unclear how many children living in poverty rely on a public-transit dependent adult, the links between transportation access and earning capacity are statistically quite apparent.

How much can Garrison do to fix the system? His course of action is ultimately tied to how much money the city council is willing to put into MATA’s budget.

In the meantime, the city’s two transportation unions plan to keep pushing to publicize the challenges facing citizens dependent on public transportation — and for the money to address the issues.

Until that happens, citizens like Georgia King plan to keep watching the buses. “This isn’t about one person, this is about us as a city,” she says. “We’re locked in together. We’d love to get out, but we can’t … so here we are.”