Can a symposium inspired by the works of William Shakespeare really be timely? Like the man says, “that is hot ice and wondrous strange snow.” But the Pearce Shakespeare Symposium: Jews and Muslims in Shakespeare’s World — an event three-years in the making — lands at Rhodes College in the midst of an attempted national travel ban targeting Muslims, and at a time when America’s official policy regarding Israel seems all over the place, at least. It could, just as easily, have been planned last week.

But what can Shakespeare teach us about this stuff, really? As it turns out, maybe quite a lot. And so can visiting cultural historians Jerry Brotton and James Shapiro, who’ll be in town for, “a far-ranging dialogue” about Judaism. Islam, comedies, tragedies, histories, and the story of nations.

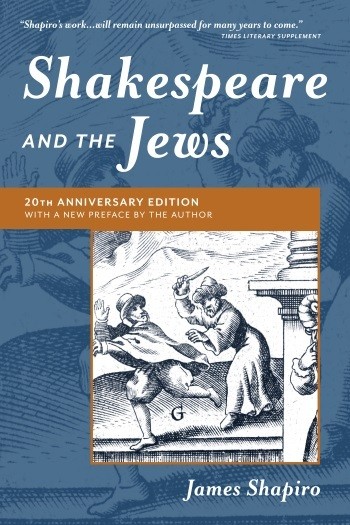

In Shakespeare in America, Shapiro considers how the plays have been used by Americans to discuss things where there’s no standard for national conversation.

“There are things that we, as Americans, tend not to talk about very comfortably,” Shapiro says, in an email interview with Intermission Impossible. “One of them is immigration. In the past, one way that those against immigration have tried to express their views on this subject is through Shakespeare.”

[pullquote-1]Shapiro’s first example is Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, “who wrote about ‘Shakespeare’s Americanisms’ in 1895, in which he argued that ‘the English speech is too great an inheritance to be trifled with or wrangled over. It is much better for all who speak it to give their best strength to defending it and keeping it pure and vigorous, so that it may go on spreading and conquering.’ Shakespeare was at the heart of the purity of our language and race; to preserve one was to save the other. It was a view that dovetailed with his view of making America great again by keeping aliens out: ‘the immigration of people who are not kindred either in race or language, and who represent the most ignorant people who are not kindred either in race or language, and who represent the most ignorant classes and the lowest labor of Europe, is increasing with frightful rapidity.’

His second example is drawn from the inaugural address of Joseph Quincy Adams at the founding of the Folger Shakespeare Library in 1932. The event was attended by numerous dignitaries including U.S. President Herbert Hoover, as well as ambassadors, cabinet members, justices, and congressmen. “Adams,” Shapiro says, “was even more blunt about how Shakespeare stood as a bulwark or wall against a flood of immigrants who have ‘swarmed into the land like the locust in Egypt.’ He too believed that Shakespeare was invaluable for preserving in America a homogeneity of English culture.”

“How ironic,” Shapiro says. “Our current government, similarly fearful of immigration, is reportedly plannin

g to end funding for the NEH and NEA—which are both so crucial to sustaining Shakespeare in America. Lodge and Adams are likely spinning in their graves.”

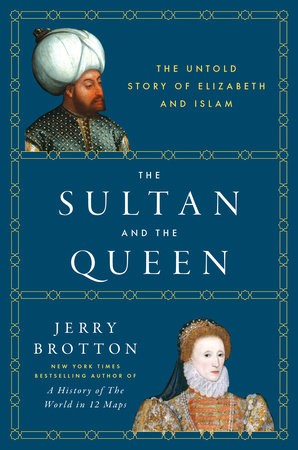

In an interview with Chapter 16, Brotton, author of The Sultan and the Queen was asked what lessons contemporary leaders might draw from Elizabeth I’s experiences negotiating with the Muslim wold during times of mounting tension. Brotton’s answer: “Don’t stop people of different faiths and beliefs from crossing your borders because it never works. The irony is that empires like the Ottomans prided themselves on their ability to absorb and assimilate multi-confessional, polyglot communities. To limit, isolate, and demonize particular religious or ethnic groups was seen as a sign of weakness, not power. Even when the Elizabethan state issued edicts trying to deport what they called “blackamoors” (mainly Muslims from North Africa), it never stuck because, guess what, everyone realized it just wasn’t workable!”